|

| Richmond’s multi-year war on landlords had some interesting developments recently.

TOPA

On November 19, following weeks of concentrated opposition and a petition signed by 1,000 opponents, the City Council, in a rare moment of sanity, walked back its previous 6-1 endorsement of a Tenants Opportunity to Purchase (TOPA) ordinance.

In September, Richmond City Council requested that staff develop a TOPA ordinance for the city. The action led to protests at subsequent City Council meetings and the launching of a Change.org petition by the Association for United Richmond Housing Providers (AURHP) that received nearly 1,000 signatures.

At Tuesday’s meeting, Richmond Councilmember Jael Myrick apologized for the manner in which he introduced the proposal. In asking city staff to develop an ordinance, Myrick submitted an example of a TOPA ordinance authored by the East Bay Community Law Center, where he is employed as program director for the Clean Slate Practice. That 14-page proposal was highly criticized by AURHP as giving far too much power to the city over private property transactions.

Rent Control and Just Cause

On November 26, the Richmond City Council received the annual report from the Richmond Rent Program. The program was established to implement Measure L: The Richmond Fair Rent, Just Cause for Eviction, and Homeowner Protection Ordinance. It was largely based on the broad premise that landlords were exploiting renters, charging excessive rents and evicting tenants without good cause.

Although the presentation by the Rent Program was impressive, involving a slick brochure (non-recycled paper) and an expensive video, it provided little information about the effectiveness of the program. It revealed that the program now has a budget of $2.25 million collected from landlords to pay a staff of 21, including nine student interns. The ordinance fully covers about 40% of Richmond’s 37,000 housing units (7,802). Another 11,457 units are covered only by the ordinance’s eviction protections.

What the presentation did not address includes:

- How many rental units have been taken off the market because of Measure L?

- How effective Measure L has been in reducing excessive rent increases?

- How effective Measure L has been in reducing evictions for other than “Just Cause?”

The report tells us that there were 4,211 termination of tenancy (eviction notices) filed during the 2018-19 fiscal year. It also tells us that 100% of the evictions were, in fact, for “just causes” allowed under Measure L. Not surprisingly, over 96% of evictions were for failure to pay rent, a solid “just cause.” What this is telling us is that landlords play by the rules, and there was no need for the Rent program to intercede to reverse massive unlawful terminations.

There has been no effort by the Rent Program to document its effectiveness in moderating rents and stopping excessive increases. If it had been effective, one would expect Richmond’s level of rents and rent increases to be lower than cities without rent control, but that is not the case.

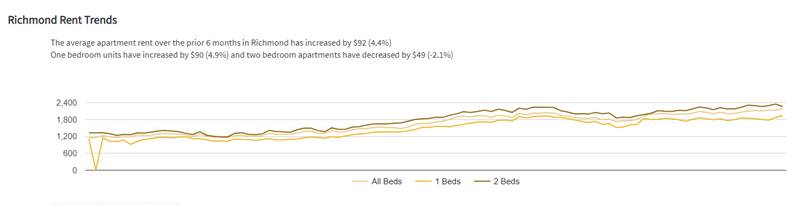

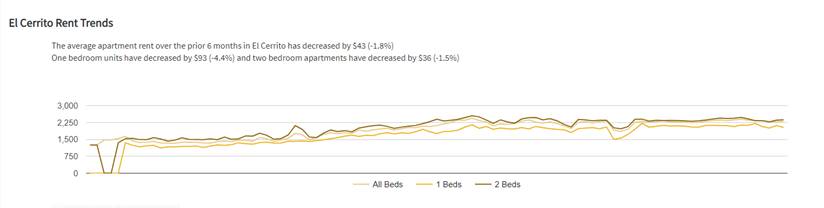

In Richmond, residential rent has increased 4.4% over the last six months, while in neighboring El Cerrito, without rent control, rents have decreased by 1.5% (Source – Rent Jungle) A reasonable conclusion might be that Richmond’s rent control program is actually increasing rent, perhaps by discouraging development of new rental units and motivating owners to take existing units off the rental market, thereby driving down supply while demand remains constant or is rising.

During the Rent Program presentation, Councilmember Willis asked Director Nicholas Traylor for some “war stories” about the effectiveness of the Rent Program. One they both enjoy telling and retelling is how Mr. Traylor was able to intervene in a proposed but entirely legal rent increase by an “affordable housing” complex that is not subject to rent control because it operates under HUD regulations. Mr, Traylor, to his credit, was apparently successful in persuading the owners to moderate the rent increase. Ironically, the mediation that achieved the moderated rent increase was not a function of rent control described under Measure L. This mediation could have easily taken place and been just as effective without the $2.5 million bureaucracy established by Measure L.

For the cost of a $2.25 million annual expenditure on the Measure L bureaucracy, the Rent Program could pay the full cost of housing for 85 families at the average Richmond apartment rental rate or subsidize the cost for hundreds of renters so that their housing costs are within the accepted 30% of adjusted gross income.

Finally, the Rent Program has, if anything, been a financial windfall for its bureaucrats. While capping rent increases at the level of CIP inflation, the Rent Board imposes no such limitations on its own highly paid staff, granting a pair of 6.7% raises to Nicholas Traylor and a 19.2% raise to Paige Roosa, only two years out of college.

Rent Program Total Compensation

Fiscal Year: |

2017/18 |

2018/19 |

2019/20 |

Nicholas Traylor |

$214,908 |

229,400 (6.7% raise) |

$244,938 (6.7% raise) |

Paige Roosa |

$150,418 |

157,939 (5% raise) |

$188,400 (19.2% raise) |

Fair Tenant Screening Ordinance – Item H-20 on the December 3 Agenda

On its face, the Fair Tenant Screening Ordinance seems to have a reasonable goal – saving prospective tenants from having to pay up front for screening reports required by multiple landlords. The cost of a screening report can range from $10 to $35, and under state law, a landlord can charge an additional reasonable fee for processing and reviewing a screening report.. A tenant applying to five different landlords, for example, might have to pay $250 just to reimburse the landlords for obtaining screening reports and processing the applications, a potential burden especially for financially challenged renters. The ordinance would, instead, allow a tenant to obtain a single report from a screening agency and force each landlord to accept it.

This is another project of the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, formerly known as the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, which is the sole cited source of information in the staff report for drafting this ordinances. This Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley has a history of advocating positions adverse to Richmond’s interests. They were significantly responsible for killing the Global Campus project, and they were strong advocates of rent control .They are also enamored with creating complex and expensive bureaucracies to implement their proposed programs.

The proposed Fair Tenant Screening Ordinance has serious flaws. For example, the only definition of “Tenant Screening Agency” is as follows:

“Tenant screening agency” shall mean any person or entity which, for monetary fees, dues, or on a cooperative nonprofit basis, regularly engages in whole or in part in the practice of assembling or evaluating information about Applicants, including but not limited to credit history, eviction history, employment history and conviction history, for the purpose of furnishing reports to housing providers.

There are thousands of “tenant screening agencies.” No doubt some do a good job, but many depend on automatic web searches with unverified results. Some are more comprehensive than others. Prices range from as low as $10 to maybe $35. Forcing a landlord to accept information from a questionable source not of the landlord’s choosing is not fair to the landlord and could result in discrimination against the tenant who might use the cheapest agency with the least reliable and comprehensive report save money.

The California legislature has already debated this issue extensively and has passed laws to try and make the process fair to all parties.

- Fees: A landlord may charge a maximum screening fee of around $35 per applicant.

- Purpose of Fees: The fee may only be used for “actual out-of-pocket costs” of obtaining a credit report, and the “the reasonable value of time spent” by a landlord in acquiring a credit report and checking personal references / background information. (Civ. Code §§ 1950.6)

- Landlord’s Duties: A landlord who uses the screening fee to obtain the potential tenant’s credit report is required to give the applicant a copy of the report upon request. (Civ. Code §§ 1950.6)

- Unit Availability: A landlord may not charge a screening fee if no rental unit is available (unless the applicant agrees to otherwise in writing). (Civ. Code §§ 1950.6)

- Receipts: A landlord is required to provide an itemized receipt when collecting an application screening fee. (Civ. Code §§ 1950.6)

If the main objective of this is to reduce the cost to prospective tenants of submitting a rental application, there are some solutions that would not require a bureaucracy to administer:

- Simply ban any fees and let the landlord recoup the screening cost by amortizing it in the rental. The downside of this is that it might incentivize the landlord to reduce the field of considered tenants

- Limit the cost of screening to a low amount. The CAA has a program that ranges from $16 to $26.

Source of Income Ordinance – Agenda Item H-21

The second landlord targeted item on the December 3 Agenda is the Source of Income Ordinance. The intent is to prevent discrimination against Section 8 tenants, who derive part of their rental payments from HUD.

Advocates for this ordinance would have us believe that it is discrimination against poor people that makes some landlords shy away from Section 8 tenants, but it is more likely the burdensome layer of HUD regulations and bureaucracy that goes far beyond a check in the mail.

But more importantly, the California Legislature has already solved this problem by passing SB 328, signed into law this year, which makes H-21 redundant (see below). California landlords can’t discriminate against renters with housing vouchers, new law says

BY HANNAH WILEY

OCTOBER 08, 2019 06:44 PM

Disabled woman describes her frustration in trying to find a place to live. BY CRAIG KOHLRUSS

During his first stop on a statewide housing affordability tour on Tuesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law to prohibit landlords from discriminating against tenants who use housing vouchers to pay their rent.

Current law already bans landlords from discriminating against a tenant based on his or her source of income. But landlords have to be willing to rent a unit to a family or individual using a voucher. If accepted, the tenant’s program directly pays the landlord what the voucher covers, and the renter pays the rest.

This law expands the definition of income to encompass “federal, state, or local public assistance and federal, state, or local housing subsidies.” The assistance is generally known as “Section 8” housing, though the law applies to other programs as well.

An estimated 300,000 low-income Californians rely on state and federal housing vouchers to avoid homelessness and deep poverty, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

“(Vouchers) can also help low-income families — particularly African American and Hispanic families — raise their children in safer, lower-poverty communities and avoid neighborhoods of concentrated poverty,” the center noted in its 2016 research on the programs.

A coalition of housing advocates and civil rights groups backed SB 329 as a part of their effort to solve the state’s homelessness and housing affordability crisis.

During a Senate floor debate in September, state Sen. Holly Mitchell, D-Los Angeles, said that landlords would still have the ability to screen these applicants using “the same criteria they use for any other potential tenant.” They would not not be required to lower rents to accommodate the tenant, and they’re not expected to forgo verification standards like credit checks and evidence of income.

“They would simply be barred from refusing someone’s application based solely on their source of income,” the Los Angeles Democrat and SB 329 author said. “The bill will enable families with housing assistance to successfully apply for and obtain, if they qualify, housing that they can afford in neighborhoods of opportunity.”

Republicans routinely argued against the measures, backed by groups that represent landlords and realtors. The California Association of Realtors opposed the bill because it said SB 329 will “mandate” landlords to accept housing vouchers.

“EVERY residential rental property owner will be effectively forced to enter into a contract with the local housing authority requiring they accept tenants who use Section 8 housing vouchers to pay a portion of their rent,” the association wrote in the bill analysis. “Instead of fixing Section 8 by remedying this and other problems to attract more landlords to voluntarily participate in the program, SB 329 creates new mandates.”

Newsom signed the legislation alongside a handful of other renter protection measures, including one to cap annual rent increases at 5 percent plus inflation and prevent landlords from evicting tenants without “just cause.” He is scheduled to continue his tour through San Diego and Los Angeles, where he is expected to sign additional housing measures.

“About a third of California renters pay more than half of their income to rent and are one emergency away from losing their housing,” Newsom said on Tuesday. “The bills signed into law today are among the strongest in the nation to protect tenants and support working families.” |