|

|

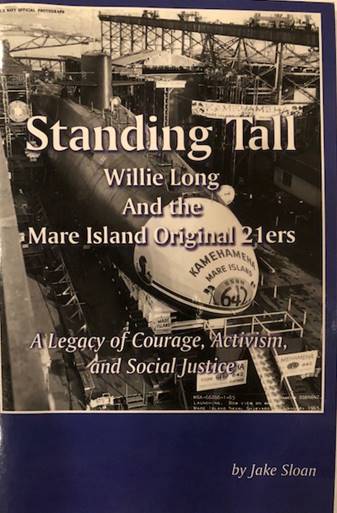

Standing Tall: Willie Long and the Mare Island Original 21ers is part of my summer reading program that I want to share.

On October 18, 2018, at 6:30 PM, at the Richmond Main Public Library, author Jake Sloan will be discussing his recently published book Standing Tall: Willie Long and the Mare Island Original 21ers.

I found the book to be enlightening and fascinating, particularly in the context of Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front National Historical Park and the Richmond shipyards. Before we had the benefit of Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin’s popular talks about her first hand experiences in Richmond in WWII, we too often accepted the version of history that blacks and whites worked side by side in the Shipyards for the same wages and presumably lived happily ever after in a newly equitable society.

Unfortunately, this was not the case following WWII, and it was not the case even fifteen years after the war ended. Standing Tall: Willie Long and the Mare Island Original 21ers is the story of how 25 men stood up to long-standing discrimination in hiring, training, promotions and equal pay at Mare Island Naval shipyard in the early 1960s. Jake Sloan was one of eight Richmond residents who were proud members of that group.

After the “original 21ers” filed a complaint with the federal government, great changes were made at Mare Island and at other federal installations throughout the United States. Jake has now written a carefully researched book that tells the story of events leading up to the filing of the complaint and short and long-term impacts, both positive and negative. Jake will address both the resulting positives and negatives during the discussion.

The book stands as a testament to sacrifice, the value of organization, solidarity and risk associated with speaking up. The book acknowledges the courage and resolve that is indicative of the struggle for justice for African American people. The work is essential for the realization that there are those who attempt to tell the story of African American people but what they produce is biased, grossly distorted, triumphalism/revisionist and tantamount to fomented misconceptions.

The work contributes to the history of this country from the standpoint of telling a story that is not well-known, but bears witness to the need for standing up for one’s rights, the critical importance of leadership, using the approach of any means at hand as tools and the need to have a cogent agenda in the quest for equality. As part of the war industry, the more than 1,000 African American workers on Mare Island were confronted with racial discrimination in working conditions, unequal pay, hiring, training and advancement while the federal government and the larger society spewed platitudes about democracy, liberty and equality manifesting a glaring contradiction. The book confirms that freedom is not free and shows the value of collective action as opposed to individualism.

In many ways, working at Mare Island meant good jobs. Conditions for those in the production shops were usually much better than those found in the private sector for similar work, especially in the building trades. However, there had been growing dissatisfaction with the status quo among a small but growing group of the African American workers. They were tired of being paid less than whites for performing the same work. They were tired of being supervised by whites that they had trained. They were tired of being tired, as the old saying goes.

It was not easy to organize on the Shipyard. They were up against an entrenched culture that defined the roles and expectations of African American in the workplace. This thinking was entrenched in the minds of both whites and many, many African Americans on the Shipyard. In fact, they sometimes had as much resistance from reluctant and fearful African Americans as we had from whites. Many workers, both white and African American, had come from the South where such discrimination was the norm. The organizing was hard and dangerous. If the actions had become known to the leadership at Mare Island, they would have been fired.

Over the years after the filing of the complaint, progress was made, but there were still challenges when the shipyard closed. For one thing, the leadership at the shipyard never admitted to discrimination. Everything was blamed on misunderstandings. Also, ironically, some of the people who refused to sign with the group, or even join later, received some of the best promotions.

Across the country, there are unmarked graves of unsung heroes and heroines who represent countless acts of resistance which stand as testaments to the enduring struggle of African American people in the struggle for equality. The book is a monument that brings to light a virtually unknown group of men who made history by standing up for what was right and just.

Jake is almost a life-long resident of Richmond, having grown-up in North Richmond. Although a high school drop-out, after voluntarily leaving employment at Mare Island, he attended Contra Costa College, where he was an activist and student body president. He later received an MA in history from San Francisco State University. Since 1986, he has owned Davillier-Sloan, Inc., one of the leading labor-management firms in California. Influenced by Jake’s experience while working at Mare Island, the company focuses on issues of diversity and equal opportunity in the construction industry. In 2005, Jake was selected in the second class for induction into the Contra Costa College Hall of Fame.

The discussion will be led and moderated by Mckinley Williams, former president of Contra Costa College, and Joe Fisher, a local businessman and community activist. Both are almost life-long friends of Jake.

Jake Sloan

|