|

| The following is a reasonably fair discussion of RM3. I was chair of the Contra Costa Transportation Authority when RM3 was finalized, and I got to watch how it was made. As a CCTA commissioner, I was able to get $210 million allocated to the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge corridor, including major improvements to the improvements at the East end of the bridge.

Like most critical public policy initiatives, this one is not perfect. In fact, there is no such thing as perfect because everyone has their own idea of what is perfect. But it goes a long way towards addressing our most critical mobility challenges. And 69 percent of it goes to improving and expanding public transit.

If it doesn’t pass, we are in big trouble transportation-wise.

If even the bicycle lobby supports it, you know it’s a good thing. Vote Yes on Regional Measure 3. Measure 3 seeks to ease traffic congestion by raising Bay Area bridge tolls

By Michael Cabanatuan

May 20, 2018 Updated: May 21, 2018 6:00am

Photo: Photos By Paul Chinn / The Chronicle

Regional Measure 3, to raise bridge tolls, would fund specific projects such as upgrading some AC Transit bus corridors.

BART’s packed, Interstate 80 and Highway 101 are backed up day and night, it takes forever to get in and out of Silicon Valley, and places like the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, which few ever figured to be traffic trouble spots, have become hellish.

The Bay Area’s fragile transportation network is reaching a breaking point. A BART train that breaks down in the wrong place will send delays shuddering through the entire system. A big crash on one freeway or bridge will lead to hours of backups that radiate through the region.

With the Bay Area economy booming, the glut of daily commuters is overwhelming the region’s highways, bridges and transit systems, and the money it would require to pay for an abundance of needed or wanted transportation improvements is in short supply.

Regional Measure 3 on the June 5 ballot in the Bay Area’s nine counties would tackle that problem by raising tolls on the Bay Area’s seven state-owned bridges by $3 over the next seven years.

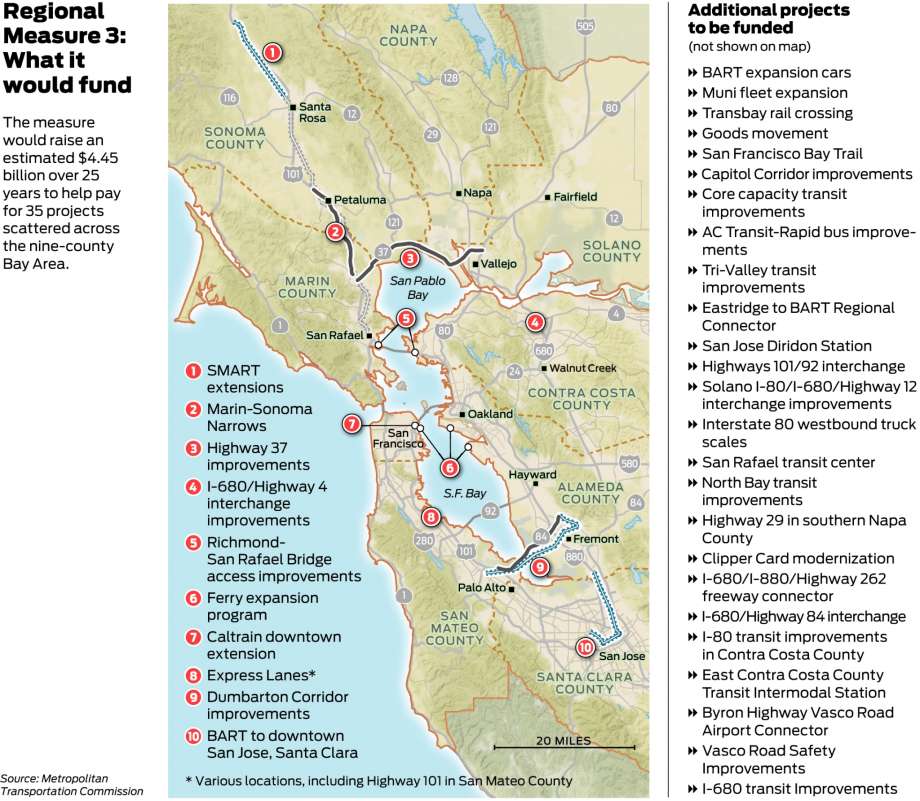

Transportation officials estimate the toll increase would generate $4.45 billion over the next 25 years for investments in 35 transportation projects that include a South Bay BART extension, a Caltrain extension into downtown San Francisco, increased ferry and regional express bus service, highway widenings and the creation of more freeway express lanes.

“This is a well-thought-out set of projects that’s scaled throughout the region and can make everyone’s lives better, reduce the amount of time they spend in their vehicles and allow them to have much better transportation options,” said Jim Wunderman, CEO of the Bay Area Council. “It’s an opportunity we have to make an investment in the region we love.”

To pass, the measure needs a simple majority of votes cast in the nine counties combined. It would raise bridge tolls by $1 in 2019, 2022 and 2025.

So tolls would climb from $5 to $8 over seven years on the Richmond-San Rafael, San Mateo-Hayward, Dumbarton, Carquinez, Benicia-Martinez and Antioch bridges. The Bay Bridge, where the current tolls are $6 during peak hours, $5 on weekends and $4 at all other times, would cost $9, $8 and $7, respectively, to cross by 2025.

Tolls on the Golden Gate Bridge, which is owned and operated by an independent district, would not be affected.

As its title suggests, Regional Measure 3 marks the third time Bay Area transportation officials have gone to voters in several counties seeking toll increases to fund major transportation projects. Both previous measures passed — RM1 in 1988 and RM2 in 2004.

The first measure helped deliver a new Benicia-Martinez Bridge, a replacement for a span of the Carquinez Bridge, widening of the San Mateo Bridge and construction of the Richmond Parkway, among others.

Projects funded by RM2 included the Caldecott Tunnel fourth bore and SMART, the North Bay’s commuter railroad. It paid for the Transbay Transit Center, BART’s extension to Warm Springs in South Fremont and its east Contra Costa extension. It also funded the Oakland Airport Connector, the widening of Highway 4, a fleet of ferry boats, and carpool lanes, which are now also toll lanes, on Interstate 580 in the Tri-Valley.

“Imagine what the Bay Area would be like without RM1 or RM2,” said Randy Rentschler, a spokesman for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission. “Imagine two lanes on the San Mateo Bridge or going back to three bores at the Caldecott Tunnel. Imagine not having a new Benicia-Martinez Bridge.”

The current measure would help fund dozens of transportation projects, all of which are supposed to be at least tangentially linked to the state-owned toll bridges or the transit systems used to skirt around them.

Most of the money — about 69 percent — would go toward mass transit projects, with 25 percent directed to roads and highways and 3 percent dedicated toward each project connecting different types of transit and improvements to benefit bike riders and pedestrians.

Photo: Todd Trumbull

Some of the projects reach across county lines and affect most of the Bay Area. Others target specific bridge corridors or geographic areas.

If the measure has any headline projects, they’d probably be the 10-mile BART extension through downtown San Jose to Santa Clara and the Caltrain downtown extension to the Transbay Transit Center at Mission and Fremont streets in San Francisco. Both are major projects, long planned, and short of funding. RM3 won’t assure their construction — federal aid will also be needed — but the toll money would bring them much closer to reality.

Other big investments from the measure would include more than 300 new BART railcars, allowing the transit system to expand its fleet; operating funds for the Transbay Transit Center; expanded San Francisco Bay Ferry and regional express bus service, money to study a new transbay rail crossing, and the creation of more express lanes that allow solo drivers to buy their way into carpool lanes. Highway 101 through San Mateo County is likely to be a priority for new express lanes, along with Interstate 880 in Alameda County.

Major highway investments would allow Caltrans to complete the widening of Highway 101 through the Marin-Sonoma Narrows in the North Bay and rebuild overwhelmed and outdated freeway interchanges at Highway 101 and Highway 92 in San Mateo, Interstate 680 and Highway 4 in Martinez, and I-80, I-680 and Highway 12 in Fairfield. Flood-prone Highway 37 across the north end of the bay would get money to help keep it open when it rains.

Photo: Paul Chinn / The Chronicle

A Capitol Corridor train destined for Sacramento arrives at the Amtrak station in Berkeley. Improvements to the Capitol Corridor’s infrastructure would be upgraded if voters approve Regional Measure 3, which would raise area bridge tolls, except on the Golden Gate Bridge.

Also included in the measure are some uncommon provisions. For example, it holds the promise of a discount — 50 cents in 2019, $1 in 2022 and $1.50 in 2025 — for people who cross more than one bridge on a single commute. Another would create and fund an inspector general for BART to improve its efficiency and monitor spending on capital projects.

The measure is backed by business groups like the Bay Area Council and Silicon Valley Leadership Group and SPUR, an urban-planning think tank. The three have joined forces to campaign for the measure, which they consider critical to the future of the Bay Area.

Carl Guardino, CEO of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, which has campaigned for passage of many regional and local transportation tax measures, likes to say he “hates taxes but hates traffic more.”

He’s been working on the RM3 campaign for months, and said Bay Area residents understand the need for the toll increase.

“What we’ve overwhelmingly found,” he said, “is that when people see the list of projects, they understand it is a regional effort, and they say, yes, we need and support the investment.”

No organized campaign has surfaced to fight RM3’s passage but critics include an East Bay congressman, a Silicon Valley mayor and a Marin environmentalist and MTC critic, all of whom have been vocal in their opposition.

Rep. Mark DeSaulnier, D-Concord, argues that the measure is a bad deal for East Bay residents who use the bridges more and, therefore, pay most of the tolls while Santa Clara County, which has far fewer toll payers, is getting a disproportionate share of the money. Cupertino Vice Mayor Rod Sinks persuaded his City Council to oppose RM3, saying it steers too much money to San Jose while neglecting the west side of the Santa Clara Valley, whose highways are choked with congestion.

“There are no projects on this side of the valley — and we are impatient,” he said. “We have to bring people to work in our cities, and this does nothing toward that.”

David Schonbrunn, a Marin resident who heads Transportation Solutions Defense and Education Fund, submitted voters pamphlet arguments against RM3. He says the measure will exacerbate, not reduce, congestion, and ignores the need to get people to share rides rather than drive alone.

Instead of creating a regional network of express lanes that encourage solo drivers, and building costly transit projects, he said, the MTC should promote and encourage the use of carpool lanes.

“This is not about building stuff,” he said. “This is about changing behavior.”

Rentschler, the MTC spokesman, said he understands opponents who think they’re being left out, and he cautioned that even if RM3 passes, it won’t make all of the Bay Area’s traffic troubles disappear or fund all of its transit needs, like a second transbay rail crossing.

“Considering all the fixes we need in the Bay Area, there are going to be people upset they don’t get theirs included,” he said. “I get it. It doesn’t take more than a day driving around in the Bay Area to figure we can’t get all the infrastructure relief we need from RM3. We need more.”

Michael Cabanatuan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: mcabanatuan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @ctuan

|