|

| Tomorrow, March 26, 2017, my father, Thomas Franklin (Tom) Butt, who died at the age of 83 in 2000, would have been 100 years old. His father (my grandfather) lived to be 97. I think my father inherited the family genes, but it was lung cancer that ended his life earlier than expected.

Thomas Franklin Butt was born in Eureka Springs, AR on March 26, 2017, the last of seven children born to Festus Orestes (known as F.O.) Butt and Essie Mae Cox Butt.

The Butt family in Eureka Springs late 1930s. Top: Jack Butt, Joe Butt and his wife Mary, John Butt, F.O. Butt, Tom Butt and Bob Butt. Lower: Frances (wife of Jack), Dorothy Butt, Faye (wife of John), Essie Butt and Kathleen Butt

Eureka Springs had peaked in the 1880’s as a popular spa and at that time was one of the largest towns in Arkansas. My grandfather was a self-made lawyer and businessman who did not attend law school but instead “read the law” under the tutelage of a local attorney, passed the bar at age 19 and became an attorney. In addition to his law practice, my grandfather served two terms as mayor of Eureka Springs; a term as superintendent of schools for Carroll County; two terms (1897-1900) as representative for Carroll County in the Arkansas House of Representatives; two terms (1901-1904, 1927-1930) in the State Senate where he was president pro tempore. He was a delegate to the Arkansas Constitutional Convention of 1917-18 and was elected chancellor and probate judge of the 13th Chancery Circuit by the Bar of the Circuit to serve in 1942-43, during his son John's service in the United States Navy in World War II. One of his more interesting law clients was Carry Nation, the saloon smashing crusader of Women’s Christian Temperance Union fame.

The Butts came from Illinois by way of Kentucky and Virginia, and my great-grandfather William Alvin Butt fought in the Civil War for the North in the 126th Illinois Infantry. My great grandfather Cox came from Alabama and fought for the Confederacy. The Civil War was still a topic of hot discussion in my grandparents’ home nearly 100 years after it had been settled.

1929 in Eureka Springs, left to right, my grandmother Essie Butt, my dad and his dog “Don,”, my Uncle Jack Butt

My father grew up in Eureka Springs, where he attended local public schools. During summers while he was in high school, he had a job life guarding at a local resort on Lake Leatherwood. He graduated from high school at age 16, and began attending the University of Arkansas some 45 miles away in Fayetteville. At least one of his siblings was also at the University, and for some time, my grandmother moved with them to Fayetteville and “tended house,” bringing along the family cow.

Thomas F. Butt

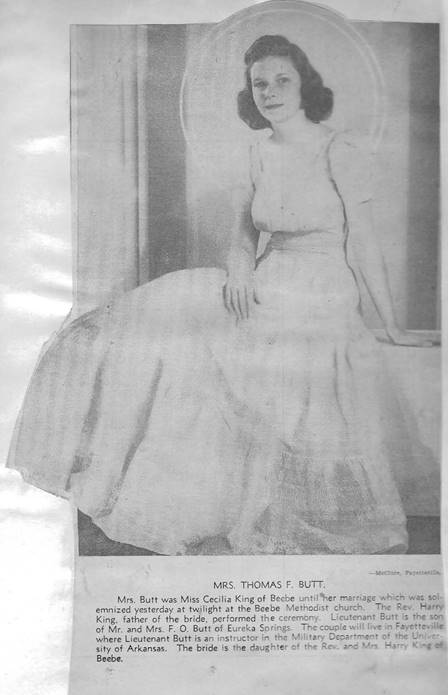

He graduated cum laude from the University of Arkansas School of Law in 1938 and was admitted to the bar at age 21. For the next two years, he practiced privately in Fayetteville and served on the faculty of the University of Arkansas Law School. Commissioned in the U.S. Army Reserve as a second lieutenant of Infantry at graduation, my father was called to active duty in 1940. My mother and father met at the University of Arkansas and were married in April of 1942 at the home of my King grandparents with my grandfather King, a Methodist minister, presiding. My mother was a student and my father was on the Army ROTC faculty.

Wedding of Thomas F. Butt and Cecilia King, April 25, 1942

In the early years of World War II, my father was stationed in several locations training infantry, among the last of which was at the New Mexico School of Mines in Socorro, near Albuquerque, where I was born. My mother had followed my father to New Mexico, where they rented an old adobe ranch building that had been divided into a duplex.

My mother had spent the summer of 1941 in Hawaii visiting her aunt Susan and Uncle, Col. Edgar King, who was Chief Surgeon for the Hawaii Department. She recalls dating young men who were on their way to China to serve as pilots in the clandestine Flying Tigers, formed to help defend China from the Japanese aggressors. (At Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, Col. Edgar King handled all the casualties (for all service branches). He had believed months in advance of the Japanese attack that Hawaii was vulnerable and had requisitioned adequate medical supplies. He was later cited for outstanding service, promoted to brigadier general and held the title Command Surgeon, United States Army Forces, Central Pacific.)

About the onset of WWII, my son Andrew transcribed the following from my father in 1991:

I was in Fayetteville, Arkansas, on a Sunday afternoon on December 7, about two o'clock. My roommate and I had just finished a late lunch and were just starting to play bridge with our two girlfriends and had the radio on. We were both in the army at the time and were second lieutenants. Of course we were shocked, that is shocked in the sense of being startled and depressed that this had happened so unexpectedly, and beyond that we were not particularly surprised because it had been thought by many people both in the government and just ordinary citizens for a year or more that there was a good chance that the United States might sometime get drawn into the war. I had been in the army over a year before Pearl Harbor was bombed and worked as an instructor at the University of Arkansas for the ROTC program. We were sorry to know we were at war and that it would probably be a long war and that many people would be killed and that it was a bad thing, but having realized that, we were very patriotic and we were very full of energy and very anxious to be a part of it and to get on with it and to whip the hell out of the enemy.

After Pearl Harbor we were just kept on duty at the University, because all of the military services, the Army, the Navy, the Army Air Corps, the Marines set about immediately to augment and increase the number of young men in the ROTC and training programs, so we stayed right here at the University and in the space of six months we had about two thousand young students training in the program where before that we only had about five hundred.

My parents were lucky to stay at the University of Arkansas for a time, but my father was moved around from assignment to assignment, with my mother following until I was born on March 23, 1944, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he was at the New Mexico School of Mines in nearby Socorro as an instructor in an Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP). This was a program designed to give special college training to young men already in the military. Many colleges and universities across the nation had similar units.

Thomas F. and Cecilia Butt with Tom K. Butt, 1944, prior to leaving for the European Theatre of WWII.

My mother later wrote:

The then Capt. Butt had received Army orders in December 1943 to go to Socorro where he would work in an Army officers training program at the School of Mines there. We made the long trip out slowly as I was about seven months pregnant. Upon arriving, we went to a little old hotel (the town’s only) at the end of the road, staying there for a few days looking for housing. We eventually moved into an adobe duplex which had originally been a one-family house, the home-place of a ranch complex. It was a dreary vista for any eyes and a difficult one for a pregnant, sickly female. Shopping was traumatic, with only naked, cold rabbit offered in the grocery meat counters, or fried, the only meat on the menu in the two town restaurants. Overly hot Mexican food was an alternative. There being no doctors or hospital in Socorro, our frequent weekends to Albuquerque to see the obstetrician offered a chance to enjoy the hospitality of the lovely Alvarado Hotel there. The Santa Fe charged right up to the doorway of the hotel where Indians in native garb waited to show and sell their arts to incoming tourists. Literally, it was a "Gateway to the West" as the sign over the entrance gate stated.

To return to our arrival in Socorro, and the little hotel there where we went on our arrival night, there was much scurrying about as a large party was to be held that evening. Since visitors at the hotel were few and Tom's position at the local college made him already known, we were invited to join in the festivities. The party was a birthday celebration to honor the grand dame of Socorro, the beloved Senora Baca. All the town seemed to be there to pay tribute to the tiny little lady of 90, beautifully dressed in an ankle length black silk of an earlier day, with lace and jewels to make a picture perfect image. She and her family were among the earliest, and surely the most distinguished, of the Socorro citizens and one of the few aristocratic Spanish families to still be social, political and economic leaders. Her late husband, El Fago Baca, had been their sheriff in territorial days, as well as U.S. Marshall and legislator.

The senora reigned that evening as a queen might, graciously greeting all well-wishers from her throne-like seat in the large hall. We were enchanted. It was nearly a year later, back in Batesville, that I learned from Aunt Dan that the same Senora Baca had been her dearest friend in those much earlier days when they were frontier wives together at Socorro, the senora of landed Spanish gentry and Aunt Dan, who followed the Santa Fe through the wilderness of New Mexico. Time and the world become swiftly small for us. The new orders for overseas duty had arrived the day after the baby’s arrival in a hospital in Albuquerque.

My father spent a short time in Ft. Worth at another high school ROTC program before shipping to Europe as a legal specialist in foreign claims. He disembarked at Omaha Beach in Normandy in September, 1944, about three months after D-Day, and then followed the front through France and Belgium where he commanded a small detachment (Claims Office, Team 6816) settling claims of Europeans against the American military.

He moved from place to place through northwestern France and eventually into southern Belgium until the war ended in the spring of 1945.

More of Andrew’s 1991 interview:

I saw service in the United States, and in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and Germany, (pause) Oh, and England. I went overseas in 1944 after the Normandy invasion. I arrived at a little bitty town on the west coast of Scotland, called Greenock spelled G - R - double E - N - O - C - K, and it was a port capable of handling large ocean - going vessels, and I went over on a former French luxury liner called, the Isle de France, and it had been put into war service and stripped of all its elegant interior and arranged for enough bunks and space to carry about four thousand or five thousand soldiers. Because I was a lawyer, the army had sent out word to various installations all over the United States saying that there was a need for lawyers and insurance agents and doctors and real estate claims adjusters to work with what were called foreign claims teams in the foreign claims service, and our job was to set up a place to work on the European continent and there received the complaints of the civilians who claimed that the American soldiers had stolen or damaged or ruined their property. They were making a claim against the United States to pay them the value of their lost, damaged, or stolen property, caused by the thievery of American soldiers or the wrongful damage of property. That entire operation was called the foreign claims service, and our job, as I say, was to receive the foreign citizens, to investigate them, and to determine if the claim was fair and to determine if the American soldiers had done the damage, and if so authorize payment, but equally to determine if the American soldiers didn't do it and if they were not negligent in doing so, than the claim was denied. There was an absolute rule that any damage caused by combat action, the United States would not pay for, because that was just a necessary result of warfare and of course the United States had treaties with all these countries, and it was agreed that the U.S. would not be obliged to pay for any damage caused by combat. But for example if a soldier got drunk on pass and broke windows or ran his jeep into the fence of a citizen, or whether he was drunk or not, if he was just a no good bum and he broke into a bakery shop and stole a bunch of bread or whatever, he was just a plain thief, and when that was established the United States would pay.

I found it extremely interesting to get to know something of the country of France and Belgium and Luxembourg and Holland simply by being in a foreign country that I'd never been in before, and getting to know a good many of the citizens of those different countries, England too of course. The foreign claims service and the unit I belonged to was not a combat army unit, we were not a fighting unit, but since we were on the continent and in the area of operations following immediately behind the area of combat we saw firsthand the results of fighting and battle damage and saw the results of the heavy bombardment by the English and American air forces, and of course we could see and hear the bombers flying over, day and night, and that was inspiring. Those are ours, those are our airmen up there; we're just whippin' the hell out of those Germans, (laughs).

I never did see any of the enemy in wartime, but I saw a good many German prisoners immediately after the war, and they, of course, had either surrendered or been otherwise captured and for a few months after the war in Europe was over, I was still there waiting to get sent home, and we were mainly just marking time waiting for our orders to be sent home. We had to have a place to live and to eat and keep alive, (laughs) like anybody does any time and for quite a while we, meaning a large number of American officers were assigned quarters in, oh I guess what you could call hotels and apartment buildings, that sort of thing, and German prisoners were there to cook and serve and make the beds and keep house for us.

When I arrived in September, of 1944, and you will remember that what we called and what history calls D-Day was June 6, 1944 and the actual fighting, the invasion was very, very heavy fighting, so, although I didn't actually land in France until about the first week in September, which would have been three months after the invasion, the fighting was still going on less than fifty miles away. So the first thing I saw were bombed out bridges and burned villages and chewed up ground, where the tank warfare had taken place, and just the general wreckage of heavy warfare. We landed on Omaha beach, where the invasion forces had, and the great big steel barriers that the Germans had put up were still in the water, and lots of barbed wire, and all the German pill boxes, heavy concrete bunkers were up on the ledge overlooking the coast with the knocked out German guns, they were all still there. There was very extensive battle damage of bombardment and artillery damage all through France and Holland. We were stationed in the Ardennes forest, where the heaviest tank fighting and infantry fighting during the so called Battle of the Bulge, took place. And we were stationed after the fighting of course, but there were just burned out tanks all over the place, and you could see where trees had been just mowed down by artillery fire and so on, so that was just quite a thing to see that, in the wake of battle, the damage that had occurred.

Our family was fortunate to accompany my father to Europe in the 1990s, after my mother died, where we visited the areas in which he had traveled in World War II. We started at the Normandy invasion beaches and went on to Rouen, Paris and the Belgium Ardennes, where we took a canal boat trip on the Meuse River. My father recalled a quick trip to Paris shortly after its liberation and how he could still smell the wonderful hot baguette given to him by a local baker. We visited Bastogne and the site of the Malmédy Massacre, where may father teared up with still painful memories. We ended by finding the Chateau in Belgium where he had last been stationed in one of the outbuilding. It was virtually unchanged but had long since become a summer youth camp.

After leaving active duty as a major, my father and mother made their home in Fayetteville, Arkansas, where he began a private law practice in 1946. He remained in the Army Reserve, however, retiring after 34 years as a brigadier general in the Judge Advocate General’s Corps. He held the mobilization designation as chief judge of the U.S. Army Judiciary, the highest Army Reserve assignment in the Judge Advocate General Corps, receiving the Legion of Merit in 1970.

One of his first cases went to the U.S. Supreme Court. The telephone company sued a woman who allowed university students free use of a telephone at her cafeteria. The telephone company accused her of cutting into its profits, saying a pay phone should be installed at the cafeteria for student use. The woman hired my dad, and the high court sided with him. It ended up as his only case before the Supreme Court. "I was able to brag after that that I won every case I ever had in the Supreme Court," my dad liked to say.

In 1949, my father’s older brother, who had been elected as chancery Judge before going into the Navy, was killed in a vehicle accident. My father ran for election to fill the empty seat and was elected chancery and probate judge in 1949 at age 32. After taking office on January 1, 1950, he was re-elected each six years thereafter and served continuously for 50 years until his retirement and death in 2000.

Thomas F. Butt 1950

During my growing up years, my father was kept busy by both his professional work as a judge and his Army Reserve assignments. He often brought work home to prepare opinions on court cases, and he used his vacation time to attend various schools and other postings related to his Army Reserve duty. We did get in a vacation every other year or so, making a trip west to the national parks, and a trip east to Washington, D.C., and all of the American heritage sites like Monticello and Mount Vernon. On the trip to the west, we visited New Mexico Governor Edwin Mechem, who had been in my dad’s law school class at the University of Arkansas.

My dad was a dedicated Civil War scholar, and we also visited a number of battlefields. When we were in Washington, D.C., visiting the Capitol, Senator J. William Fulbright asked him if there was any particular senator he would like to meet. My father named Barry Goldwater, and the introduction was arranged.

He was active in Scouting during the years my brother and I were that age, and he took the whole family to Philmont Scout Ranch one summer where he was taking an adult leadership course. He taught me all of the basic survival skills – how to drive, swim, shoot, hunt and fish, and how to guide a boat through the whitewater. The most common family outing was a weekend fishing trip, sometimes combined with a float trip on one of the local Ozark Rivers – the White, Kings, West Fork or Buffalo. My parents both liked to fish and float the Ozark rivers, and sometimes on a Sunday Afternoon, we would float right though a river baptism conducted by one of the country Baptist churches.

We also spent a lot of weekends at either my grandparents Butt’s home in Eureka Springs or my mother’s parents’ home in eastern Arkansas. All of my father’s brothers were lawyers, except one who was a doctor. They loved to gather at my grandparents’ home in Eureka Springs and talk politics, law and anything else well into the night. I remember one time they had an extended argument about whether pigeons were good to eat. The opinions ranged from gourmet (squab?) to inedible. Finally, one of the brothers grabbed a .22 and shot a pigeon off the roof. After plucking, roasting and consuming the bird, the range of opinions remained about the same – with no one willing to back down.

When I was in junior high, my father took me duck hunting in eastern Arkansas near a town called Stuttgart, a famous part of the Mississippi flyway. A lawyer friend of my father’s was a member of the club. It was run by “trusties” on leave from the State Penitentiary. Among the other guests were a group of rocket scientists from Huntsville, Alabama, including the famous Werner Von Braun. It was a pretty basic place, just an old shack on a levee, and we were all in bunk beds in the same room. I was, of course, thrilled.

My father was pretty much a “straight arrow.” The only time I saw him intentionally break the law was when he shot a squirrel out of season because my grandfather King insisted he had to have it, along with twelve other kinds of meat, for a Mulligan Stew he had made for some special occasion. He was a lifelong Democrat at a time when even judges had to declare their political affiliation. However, in those days, there was only one party in Arkansas, and that had been the case since the Civil War. I asked him one time if it bothered him that Arkansas had only one political party. He replied that Arkansas actually had two political parties – the Democrats that are in office and the Democrats that are out of office. Although he was Democrat, he was far more conservative than I, and probably would have been a Republican if the politics of the time would have allowed it.

Thomas F. and Cecilia Butt about 1972 when he retired as a brigadier general in the U.S. Army Reserve

My father, as well as my mother, had been smokers probably beginning in their teens. They only stopped in the late 1980s when my mother had to go on oxygen because of emphysema. My mother died in1991 of complications with asthma and emphysema.

My father contracted lung cancer in the fall of 1999 and died in May of 2000. He did not officially retire from the bench until March 26, 2000, his 83rd birthday. At that time, he was the senior judge of the Arkansas judiciary and had served 50 years, longer than any judge in Arkansas history.

His official title was chancery/probate judge, but he served as judge in all the trial courts of general jurisdiction, including circuit court, criminal/civil court and juvenile court. During his tenure as a trial judge, Judge Butt’s career included: serving as President of the Arkansas Judicial Council, 14 years as a member of the Supreme Court Committee on Rules of Civil Procedure, Chair-man of the Arkansas Association for Exemplary Service to the legal profession. He was also a graduate and former instructor of the National Judicial College in Reno, Nevada.

An profile in the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette from September 21, 1998, recalled a close call he had from a deranged woman who had been before him in a custody case:

As far as Washington County Chancellor Tom Butt knew, Shirley Curry was just a person he ruled against in another emotional custody case. On July 20, 1974, the day after the ruling, a detective woke Butt by calling him at 4 a.m. Curry went on a shooting rampage, killing her ex-husband, her ex-sister-in-law and her three children -- 17, 14 and 11. She outlined her murderous plans on a cassette tape police found. "We heard the tape," the detective told Butt. "She said, 'The next person I'm after is that man in the black robe.' " Police arrested Curry before she could follow through with her threat. At 61, she's serving life without parole in an Arkansas prison.

By 1998, he was just two years short of 50 years on the bench and was getting attention for his longevity. The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette article continued:

Twenty-four years later, at 81, Butt is still trying custody cases. In 2000, 50 years will have passed since Butt, the longest-serving judge in Arkansas and perhaps in state history, was elected chancellor. He recently had a rebirth of sorts. On Aug. 31 he marked the first anniversary of his second marriage. Lawyers and others who work with Butt say he remains personable, knowledgeable, hard-working and sharp on the bench. While he hasn't lost his sense of humor, he's retained his grit, a no-nonsense attitude and a demand for decorum and proper legal procedure. Lawyers know better than to play games in Butt's court. It's a lesson a man upset over the judge's ruling in a property dispute quickly learned one day some 40 years ago. "This fellow came into my office pretty hot around the collar," Butt recalled last week. "He thought I was crooked and had been bought out by the other side. I lost my cool and said, 'You son of a b****, you get out of this office.' " The judge paused in the middle of the story, embarrassed by the memory. He was young and inexperienced. I would not do that now," Butt said, pausing again, gazing upward in thought. "Well, I'm not sure I wouldn't do it, either, because that cuts pretty close to the bone when somebody accuses you of selling out to the other side."

In 1949, his brother, John K. Butt, the chancellor in Fayetteville, died in a car wreck. The next year, Butt ran to fill the vacant spot. He won, he said, not by his own merit, but by the great respect the people had for his brother. Over the years, however, the younger Butt slowly distinguished himself. The military awarded him the Legion of Merit for his service as chief judge of the Court of Military Appeals, although he was never called to active duty. That court hears appeals from court martials in each branch of the armed forces. He retired in 1972 as a brigadier general. Other honors include the Arkansas Certificate of Merit for his work as chairman of the Judicial Discipline Commission and the American Bar Association's Award for Judicial Excellence, a national distinction given a handful of judges each year. Lewis Jones, a lawyer in Fayetteville for 43 years, says Butt has a calming influence in the courtroom. He recalled one case about 20 years ago when about 50 or 60 angry "mountain-type people" gathered in Butt's courtroom over a custody battle. The judge, like he does after all cases, explained his decision in detail and complimented both sides. "I'm convinced that's what prevented bloodshed in the courtroom," Jones recalled. State Supreme Court Justice Bob Brown and others cite Butt's colorful speech and marvel at his vocabulary. His Southern gentlemanly manner and down-home phrases impress others. "He has a really refined sense of justice and has the mannerisms and decorum of a Shakespearean actor," Brown said. "He's a real credit to the state. He's unique."

In the 1990s, challengers tried to pick him off, but he continued to prevail.

Over the last decade, some lawyers grumbled that maybe Butt was too old and had worn out his black robe. Some cite his continued opposition to court consolidation. In 1990, Butt faced a challenger for re-election for the first time in his political career. Butt won by a 3-2 margin. 1996 was tougher. He faced opposition in the Democratic primary and from a Republican in the general election. His opponents told people he was slipping. It was time for new blood, they said. There was some talk that Butt should switch parties, since Northwest Arkansas has become strong GOP territory. Butt refused and campaigned door-to-door for hours each day in the sun, shaking as many hands as he could, asking for votes. A small group of county lawyers secretly supported his Republican opponent Jim Burnett, a former judge in Lonoke County, Everett said. But the majority in the bar openly supported Butt. The incumbent lost Washington County but received enough votes in Madison County, the other county covered by his judicial circuit, to squeak by -- 25,731 to 25,473.

The close vote didn't insult Butt, despite his years of service. He said he understands that someone could legitimately make a political issue out of his age. He said people have a right to choose their leaders, even if that means he may lose. "I'm just hanging around as long as I can," he said. "My guess is that when my present term ends I'll retire as gracefully as I can." In 1997, Butt disposed of 1,321 cases compared to 1,369 filings, a rate better than average, according to the state Administrative Office of Courts. "Chronologically he's 80-plus but his mental stamina is 60," said Everett, a lawyer since 1974.

"You can't imagine the respect he has. He's a nice guy. He's learned. He's interesting to talk to. He'll take young lawyers by the ears ...to show them what needs to be done and mold them. That's what he did with my generation." For example, one day last week a lawyer asked to call his client for rebuttal testimony. Butt quickly reminded the lawyer he may call his witness but not for rebuttal testimony. He then defined the legal term. "Thank you, your honor," replied the humbled lawyer. Butt believes lawyers still have much to learn after passing the bar exam. "He proceeds to teach them," Jones said. "He's not liked generally by the young lawyers."

One lawyer, Kathryn Platt, 30, said she enjoys going before the judge. She just has to remember to stay alert and respectful, she said. Technology and society, however, have changed since Butt took office in 1950. Last week he questioned a witness at length about her caller ID box and how call-blocking works. He's also frustrated by court delays caused by interpreters for the growing Hispanic population in Northwest Arkansas. "If you ask a [Hispanic] fellow what time did he get up this morning, instead of saying '6:30, he'll ripple on for about 30 seconds and then the translator says, 'He got up at 6:30,'" Butt said. Butt doesn't appreciate his time being wasted. He'll do what the law says, even if he doesn't agree with it. He said he "detests" a law requiring him to issue domestic protective orders if shown evidence of violence. Ordering people to stay away from each other solves nothing, he said. He grew impatient last week after a couple testified they had been married for 20 years but that they never liked each other. He approved the protective order against the husband but said they should hire a lawyer and get divorced. "What these people need are to be taken out with a wet rope and given a whuppin'," the white-haired, thin-mustached, red-faced Butt said, peering behind his glasses as he rocked in his courtroom chair.

Older lawyers such as Everett openly disagree with the judge on some topics. Almost every afternoon, Everett joins Butt for lunch at Hoffbrau steakhouse on Center Street, a block from the old courthouse. Other regulars include Circuit Judge Bill Storey and Municipal Judge Rudy Moore, old Bill Clinton confidants, and attorney Woody Bassett. "It's the Round Table," Butt joked. "Although, it's not round; it's oblong. Everybody's an expert on something. All amounts of wisdom is passed around." Recently, the group was lamenting Clinton's troubles and offered theories on what the scandal will bring next. Then, they plotted mock attempts to steal a fellow lawyer's Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Bassett said he can always count on Butt for lunchtime facts or theories on the Civil War. A Confederate sympathizer, Butt would have pleased his Alabama grandfather. "My perception of the Constitution is that a state had a right to secede," Butt explains. "Well, it didn't work, and we're better off for it.

My mother died in 1991, and my father remarried an old friend, Frances Trotter, on August 31, 1997. They remained married until his death in 2000.

Away from the courthouse bunch, Butt spends his time tending his vegetable garden and spoiling his five grandchildren. Three are nearby, the children of his youngest son, Jack Butt, a Fayetteville attorney. Two grandchildren are in San Francisco with his son, Thomas K. Butt, an architect. A third son, Martin, died in a car wreck in the early 1970s after returning from the Vietnam War. His first wife, the former Cecilia King, died in 1991 after a prolonged battle with emphysema. For the last 18 months of her life, she required constant attention. Butt took her to hospitals in Denver and Tucson, Ariz., but the treatments failed. Initially, he never thought about remarrying. Later, however, he began corresponding with Frances Trotter, a friend of his late wife who had moved to Mississippi some 30 years earlier. She had recently been widowed and after a while they arranged a meeting. For their first anniversary, they spent a few days at a lakeside bed-and-breakfast Oklahoma. "After being married to Cecilia for 50 years, I forgot how to court," he said. "[Frances and I] just met each other and let each other know we found each other's company pleasant. I don't care about movies; neither does she. I like reading and she's an avid reader. We both like classical music. We figured we'd better quit seeing each other or get married. "Friends say he doesn't take himself too seriously. When he's not wearing his black robe, it lies crumpled on a chair. "I'm going to burn this damn robe someday," he growled, frustrated with the robe's difficult zipper as he left his chambers for a hearing. The day's court business had lasted longer than he thought. At 5 p.m., he quickly tossed his robe and donned his hat and wrinkled light blue pin-striped blazer. Come back tomorrow, he tells a visitor. "I've got a date with my wife," he said, smiling.

After my dad announced his retirement, the Northwest Arkansas Times wrote:

Colleagues speak of civility, eloquence of retiring judge Chancery Judge Thomas Butt will perhaps be best remembered for the decorum and civility he brought to the 4th Circuit bench during his 50-yeartenure. As news of the 82-year-old judge's retirement trickled through the law offices of Washington County Thursday and Friday, colleagues spoke highly of him and the eloquence and respect he brought to the bench. "He has one of the best reputations statewide as far as a fair and impartial judge and he's well thought of by every judge in this state," said Circuit Judge Kim Smith, who's served alongside Butt the last 13 years. "He's very highly respected by all his peers on the bench. "

Circuit/Chancery Judge Mary Ann Gunn concurred with Smith, reiterating his importance to the local bench. "I feel that his presence on the bench for the last 50 years and his leadership to the bar has been, and will continue to be, an invaluable asset to this community and the state of Arkansas," Gunn said. "He inspires not only attorneys but me as a judge. He inspires that higher calling to the law, one of honor and integrity. "Citing his battle with cancer, which he was diagnosed with three months ago, Butt announced Thursday he will retire on his 83rd birthday March 26,leaving the position open for a temporary appointee and this year's general elections.

A signed letter of retirement was sent to local lawyers, judges and media Thursday, thanking the citizens of the 4th Judicial Circuit for their support. "I have been privileged, beyond my desserts, to serve as judge for 50 years, for which I am profoundly grateful, not alone to the people who have elected and re-elected me, but as well to the members of the bar and my fellow judges, who have uniformly accorded me all courtesies and support in the administration of justice in the 4th Circuit," Butt wrote.

The Washington County Bar Association is holding a reception for Butt on March 1, his last scheduled day on the bench, and is planning another tribute to the retiring judge. "He's the most respected jurist in the state," said Kitty Gaye, bar president. "We're all very sorry to see him go. "Lawyers who've practiced in Butt's court for decades remember him as a civil and respectful judge. "I've known Judge Butt since the '50s, and have practice before him since1962," said lawyer Bill Bassett. "While to some, his manners might have seemed old fashioned, to me they weren't. They just kept demonstrating his respect for the law."

His tenure on the bench was highlighted with his service as president of the Arkansas Judicial Council in 1956 and 1957. The council later handed him the Community Service Award in 1993. Smith said local judges entered him into a national contest after he won that distinction, and he was bestowed the Award of Judicial Excellence by the National Conference of State Trial Judges during their national conference in August 1996.

Lewis Jones, a local lawyer who coordinated Butt's last run for office - one of only a few he was opposed in - said Butt made a run for the Arkansas Supreme Court years ago, but his lack of statewide recognition led to his only electoral defeat.

Butt became known for his steadfast devotion to courtroom decorum and a gift of eloquence, both in speech and writing. "He has been (a mentor) as far as the conduct of the trial and the decorum in the courtroom and the civility that a judge should always show the litigant and attorneys," Smith said. "Judge Butt never gets mad, he never gets ruffled. He's very courteous to everyone. "Lawyers remember him for the notes of congratulation or compassion he often hand-wrote them. Beneath a nearly illegible scribbling were spirit-filled words few forgot. "His ability to be eloquent, his ability to write, is something that all of us ought to strive for," Bassett said. "It's somewhat a lost art in this day and time. But he is just so articulate in the way that he writes, and the way that he speaks, and we could all learn from that."

Younger up-and-coming lawyers were also shaped by Butt's service on the bench. "In my mind, he's always been the grand ol' man of the law," Gaye said. "And he's taught generations of young lawyers how to do things, including me. "Circuit/Chancery Judge Mary Ann Gunn practiced law for 18 years in front of Butt, specializing in Chancery law. She remembers, as a young lawyer, feeling intimidated by the judicial icon. "As young lawyers, our legal education continued under his tutelage," Gunn remembered. "He was strict but fair - a kind judge who nurtured us as trial lawyers. And he engaged us intellectually as advocates of the law." Bassett's son, Woody Bassett, agreed, saying the judge had instilled important lessons in new lawyers who practiced in his courtroom. "Judge Butt has taught several generations of lawyers how to practice law, "the younger Bassett said. "I know I - and any other lawyer - feel that he's an inspiration and a leader to younger lawyers."

Gunn will be one of the last two judges sworn in by the senior member of the bench. Along with fellow Circuit-Chancery Judge Stacey Zimmerman, she stood before the veteran jurist last year to take her oath of office. "I love him and will miss him very much," she said. "As a judge, he's an icon. "In his letter of retirement, Butt said he is stepping down so citizens can have a full-time judge, something that in light of his health, he can "no longer give them." "Thus, I take early retirement with regret that I cannot fulfill my contract with the people, but with the sure knowledge that a successor will be named and elected who can and will do a creditable job the better to serve the people," Butt concluded in his letter. "I am more grateful that I can adequately express to all who have supported and helped me during my tenure of office, and I entertain the hope that my services have been generally acceptable to the public whom it has been my duty and pleasure to serve."

When he finally had to admit he was not getting any better, my dad submitted his resignation:

"This early retirement (by two years) for reasons of health, is deemed proper in the best interest of the people of the 4th Circuit," Butt wrote. "I have been privileged, beyond my deserts, to serve as judge for 50 years, for which I am profoundly grateful, not alone to the people who have elected and re-elected me, but as well to the members of the bar and my fellow judges, who have uniformly accorded me all courtesies and support in the administration of justice in the 4th Circuit.

"I have enjoyed good health for all of my adult life until quite recently when a wholly unexpected illness struck me, without warning, requiring me to leave my office for the past three months," Butt continued. "The people are entitled to a full-time judge, and that I can no longer give them.

"Thus I take early retirement with regret that I cannot fulfill my contract with the people, but with the sure knowledge that a successor will be named and elected who can and will do a creditable job the better to serve the people. I am more grateful than I can adequately express to all who have supported and helped me during my tenure in office, and I entertain the hope that my services have been generally acceptable to the public whom it has been my duty and pleasure to serve."

Thomas F. Butt had a distinguished career on the bench and the bar, as the first chair of the Arkansas Discipline and Disability Commission, president of the Arkansas Judicial Council, a fourteen year member of the Supreme Court Committee on Rules of Civil Procedure, chair of the Bar Probate Law Committee, Executive Council and House of Delegates of the Arkansas Bar Association and delegate to the Arkansas Constitutional Convention in 1979. His lifetime achievements were recognized by the American Bar Association when it selected him in 1996 as one of three trial judges nationwide to receive its Award of Judicial Excellence. At his retirement on his 83rd birthday, Hon. Dub Arnold, Chief Justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court, read an order from the Arkansas Supreme Court: “He has touched the life of thousands, and in doing so, has made his portion of the earth a better place to live.” President Clinton wrote: “Your distinguished career and your commitment to the law have set an example for so many, and your work has been a true investment in the future of our state. As your remarkable tenure comes to a close, you can be proud of creating a lasting legacy of public service.”

After my dad died, the Arkansas Legislature passed a mandatory 70-year retirement age, known informally as the “Judge Butt Rule.”

My dad and I in 1995

|

|