|

| The stories below from the LA Times are getting a lot of play. The fact is that Richmond is not significantly more affected than most other cities in California, it’s just that the media likes to use Richmond as an example. In the spirit of “any publicity is good publicity,” perhaps we should embrace this.

As San Bernardino City Manager Mark Scott was quoted in the article, “The truth is that there are cities all over the state that just aren’t owning up to all their problems.”

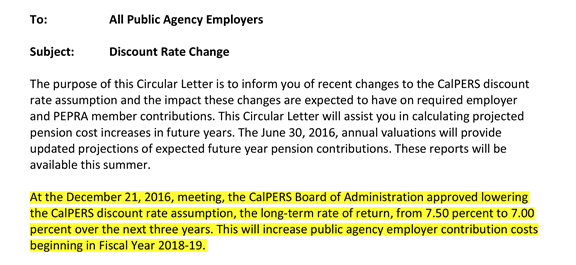

This is actually more of a CalPERS caused problem than a city caused problem. Although CalPERS remains in denial, this is largely a problem they created by vastly over-projecting the return on their investments. In December of 2016, CalPERS lowered their projected rate from 7.5% to 7.375% for FY 2017-2018 and to 7:00% by FY 2019-2020. The actual average rate of return for CalPERS over the last 20 years have averaged only 6.9%, and returns for the FY2016-2107 are a paltry 2.3%. This is at a time when the stock market is the highest on record. Every time CalPERS makes a downward adjustment, cities pay more and more.

It is a myth that Richmond is facing bankruptcy, but it is true that the City must increase revenues or decrease expenses by some $20 million in the next five years in order to have balanced budgets and meet prudent reserve and cash requirements.

The most sensible way for Richmond to move to a more stable financial position would be to transition to a defined contribution pension plan as three cities in Contra Costa County -- Lafayette, Danville and Orinda – have done. See How three Contra Costa cities avoided the doomsday of pension plans. “Orinda, Danville and Lafayette offer defined contribution plans, meaning the city knows exactly how much it pays in retirement costs when each payday arrives. Each city deposits the equivalent of 10 percent of an employee’s salary into his or her untaxed retirement fund.”

It also means that employees are being fully paid by today’s taxpayers, not their children and grandchildren.

Moving to a defined contribution plan would be politically difficult at best and illegal at worst for existing and former employees, but it could be done easier for new employees.

The only other way to avoid exponentially increasing pension costs would be to would be to increase the amount that employees contribute to pensions in the future, similarly politically and legally difficult.

Without addressing this, the quality of services provided by not only Richmond, but other cities across the state, and the state itself, will continue to decline.

Tom Butt

Cutting jobs, street repairs, library books to keep up with pension costs

Generous retirement benefits for public safety employees could help push the Bay Area city of Richmond into bankruptcy

By Judy Lin

REPORTING FROM RICHMOND, CALIF. | Feb. 6, 2017

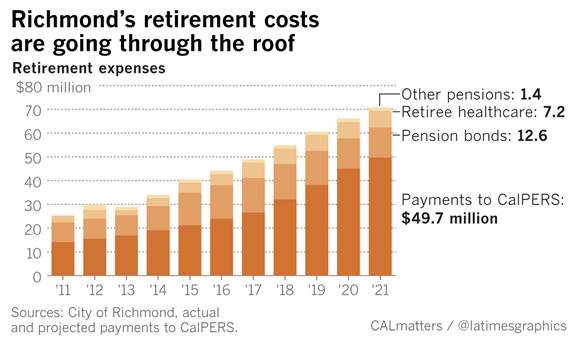

Richmond, a working-class city of 110,000 on the east shore of San Francisco Bay, has been struggling with the cost of employee retirement benefits. Pension-related expenses have risen from $25 million to $44 million annually in the last five years and could reach $70 million by 2021. (Robert Durell / CALmatters)

When the state auditor gauged the fiscal health of California cities in 2015, this port community on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay made a short list of six distressed municipalities at risk of bankruptcy.

Richmond has cut about 200 jobs — roughly 20% of its workforce — since 2008. Its credit rating is at junk status. And in November, voters rejected a tax increase that city leaders had hoped would help close a chronic budget deficit.

“I don’t think there’s any chance we can avoid it,” said former City Councilman Vinay Pimple, referring to bankruptcy.

A major cause of Richmond’s problems: relentless growth in pension costs.

Payments for employee pensions, pension-related debt and retiree healthcare have climbed from $25 million to $44 million in the last five years, outpacing all other expenses.

By 2021, retirement expenses could exceed $70 million — 41% of the city’s general fund.

Richmond is a stark example of how pension costs are causing fiscal stress in cities across California. Four municipalities — Vallejo, Stockton, San Bernardino and Mammoth Lakes — have filed for bankruptcy protection since 2008. Others are on the brink.

“The truth is that there are cities all over the state that just aren’t owning up to all their problems,” said San Bernardino City Manager Mark Scott.

Increasingly, pension costs consume 15% or more of big city budgets, crowding out basic services and leaving local governments more vulnerable than ever to the next economic downturn.

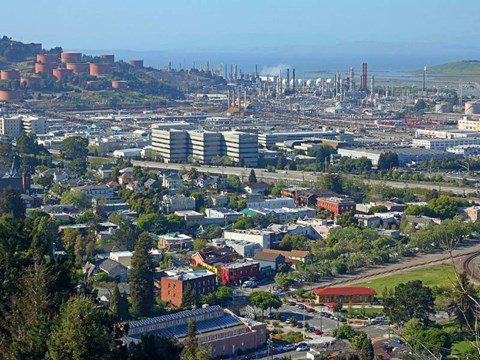

Richmond is a racially diverse, working-class city of 110,000 whose largest employer is a massive Chevron oil refinery. Like many California municipalities, Richmond dug a financial hole for itself by granting generous retirement benefits to police and firefighters on the assumption that pension fund investments would grow fast enough to cover the cost.

That optimism proved unfounded, and now the bill is coming due.

Richmond Makes Cuts To Services As Pension Costs For Public-Sector Workers Mount

Listen to a report by Capital Public Radio.

Read the story

City Manager Bill Lindsay insists that Richmond can avoid going off a cliff. Last year, financial consultants mapped a path to stability for the city by 2021 — but at a considerable cost in public services.

The city cut 11 positions, reduced after-school and senior classes, eliminated neighborhood clean-ups to tackle illegal trash dumping, and trimmed spending on new library books — saving $12 million total.

City officials also negotiated a four-year contract with firefighters that freezes salaries and requires firefighters to pay $4,800 a year each toward retirement healthcare. Until then, the benefit was fully funded by taxpayers.

“I’ve seen some of my good friends go through it in Vallejo and Stockton, and what we found out during those [bankruptcies] is that your union contracts aren’t necessarily guaranteed,” said Jim Russey, president of Richmond Firefighters Local 188.

Richmond’s consultants said the city had to find $15 million more in new revenue or budget cuts by 2021. Lindsay said the city has been looking hard for additional savings, and the police union recently agreed to have its members contribute toward retirement healthcare.

July 26, 2016

Tough sledding

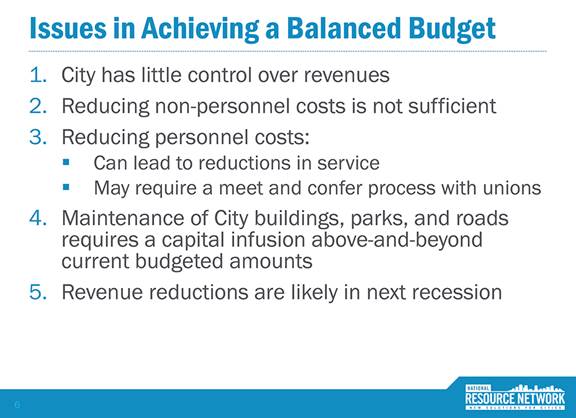

Financial consultants with the National Resource Network spelled out the daunting challenges Richmond faces in righting its finances.

“If you look at the five-year forecast, with reasonable assumptions, even with the growth in pension cost, it does start to generate a surplus,” Lindsay said.

Joe Nation, a former Democratic state legislator who teaches public policy at Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research, is not so sanguine. He reviewed Richmond’s retirement cost projections and said they leave little room to maneuver.

Over the next five years, every dollar the city collects in new revenue will go toward retirement costs, leaving little hope of restoring city services, Nation said.

“If there is an economic downturn of any kind, I can imagine that they could be pushed to the brink of bankruptcy, if not bankruptcy,” Nation said.

Last month, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), the state’s main pension fund, lowered its projected rate of return on investments from 7.5% to 7% per year. That means Richmond and other communities will have to pay more each year to fund current and future pension benefits.

Dec. 21, 2016

Lower returns, higher cost

CalPERS told local governments it was lowering its projected rate of return on investments. That means taxpayers will have to pay more to fund retirement benefits.

The change is expected to increase local government pension payments by at least 20% starting in 2018, according to CalPERS spokeswoman Amy Morgan.

An analysis by the nonprofit news organization CALmatters indicates that Richmond’s retirement-related expenses could grow to more than $70 million per year by 2021. That represents 41% of a projected $174-million general fund budget.

Lindsay said the city’s estimates of future pension costs are lower because of different assumptions about salary increases and other costs.

The city of Richmond’s pension-related budget problems have taken a toll on public services, including street repair. (Robert Durell / CALmatters)

Voters approved a sales tax increase in 2014 to help stabilize the city’s finances. But in November, voters rejected an increase in the property transfer tax that was expected to bring in an additional $4 million to $6 million annually.

Lindsay said the city was never counting on the property transfer tax in its 5-year plan. If the city needed more cash, he says Richmond has properties it can sell.

“Budget management is much more difficult in Richmond than in Beverly Hills, but you still manage it,” Lindsay said. “To say it’s spiraling out of control into bankruptcy does incredible damage to our community and it’s just not accurate.”

Richmond is especially hard hit by personnel costs because of high salaries for public employees. The city’s average salary of $92,000 for its 938 employees was fifth highest in California as of 2015, according to the state controller. The city’s median household income is $54,857.

Police officers and firefighters in Richmond make more than $137,000 per year on average, compared with an average $128,000 per year for Berkeley police and firefighters, where housing prices are more than 60% higher than in Richmond.

Public safety salaries averaged $115,000 in Oakland and $112,000 in Vallejo.

Mayor Tom Butt says of Richmond’s pension-related financial problems: “It’s a huge mess ... One of these days, it’s just going to come crashing down.” (Robert Durell / CALmatters)

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt, an architect and general contractor who has served on the city council for two decades, says the city that was once among the state’s most dangerous has little choice but to pay higher salaries to compete for employees with nearby communities that are safer and more affluent.

“You can’t convince anyone here that they deserve less than anybody in any other city,” Butt said.

Lindsay said the decision to offer higher salaries for public safety employees was strategic.

“The city council made a conscious decision to put a lot into public safety, in particular reducing violent crime. And largely, we’ve been successful,” Lindsay said.

Violent crimes have been declining in the city over the past decade with homicides dropping to a low of 11 in 2014. But

Richmond is experiencing an uptick, recording 24 homicides in 2016, according to the police department.

Part of the challenge with public safety costs dates to 1999, when Richmond, like many local governments, matched the state’s decision to sweeten retirement benefits for California Highway Patrol Officers.

CHP officers could retire as early as 50 with 3% of salary for each year of service, providing up to 90% of their peak salaries in retirement. Other police departments soon demanded and got similar treatment.

Richmond firefighters are eligible to retire at age 55 with 3% of salary for each year of service. Recent hires will have to work longer to qualify for a less generous formula under legislation passed in 2013.

Richmond’s actuarial pension report shows there are nearly two retirees for every police officer or firefighter currently on the job.

To cope with severe budgetary pressures, the city of Richmond put this Fire Department training facility up for sale. (Robert Durell / CALmatters)

In a way, Richmond is a preview of what California cities face in the years ahead. According to CalPERS, there were two active workers for every retiree in its system in 2001. Today, there are 1.3 workers for each retiree. In the next 10 or 20 years, there will be as few as 0.6 workers for each retiree collecting a pension.

Because benefits have already been promised to today’s workers and retirees, cuts in pension benefits for new employees do little to ease the immediate burden. It “means decades before the full burden of this will be completely dealt with,” said Phil Batchelor, former Contra Costa County administrator and former interim city manager for Richmond.

Today, Richmond’s taxpayers are spending more to make up for underperforming pension investments. CalPERS projects that the city’s payments for unfunded pension liabilities will more than double in the next five years, from $11.2 million to $26.8 million.

Now, the lower assumed rate of investment return is projected to add nearly $9 million to Richmond’s costs by 2021.

“It’s a huge mess,” said Mayor Butt. “I don’t know how it’s going to get resolved. One of these days, it’s just going to come crashing down.”

Judy Lin is a reporter at CALmatters, a nonprofit journalism venture in Sacramento covering state policy and politics.

Richmond Makes Cuts To Services As Pension Costs For Public-Sector Workers Mount

Ashley Gross

Monday, February 6, 2017 | Sacramento, CA | Permalink

play

Listen

3:56

View of Point Richmond and Chevron Refinery, Richmond CA, from Nicholl Knob in 2016.

User: Audiohifi / Wikipedia / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Many cities across California face rising costs for public employee retirement benefits. And for some, that’s laying bare a stark reality — it’s getting tougher to provide basic services and meet the pension obligations promised years ago.

The city of Richmond in the San Francisco Bay Area illustrates the tough choices cities are having to make.

On a recent day, Richmond Police Chief Allwyn Brown gave a tour of his department’s headquarters. It’s housed in a space that’s leased from a fiber-optics company. Richmond’s plans for a new public safety building were put on ice a long time ago, and that's not likely to change anytime soon.

Last year, the city faced a potential $13 million budget hole. City leaders had to make cuts, including leaving five police officer positions vacant.

“When I talk about how we’re staffed and how we’re equipped right now, I mean, that gets us ... to meet what the demand is, but we really want to be in a position to provide services that exceed demand,” Brown said.

Richmond Police Chief Allwyn Brown says his department has enough staff to meet demand, but he'd like to be able to provide more services. Robert Durell / CALmatters

Because of budget pressures last summer, Brown reassigned his bicycle and foot patrol team, known as BRAVO officers.

“What I hear most often is, `Hey, Chief, when are you going to be able to bring back the BRAVO officers?’” Brown said.

This belt-tightening comes at a time when he said the number of homicides has been climbing.

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt said policing isn’t the only service that’s been affected.

“We’ve neglected filling positions in departments like the library and recreation. I think the fire department’s kind of down to the bone,” Butt said. “If we cut anybody else in there, we’re going to have to start closing fire stations.”

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt says one reason it's hard to meet rising pension costs is lower income communities, like Richmond, generate less tax revenue than wealthier ones, like neighboring El Cerrito. Robert Durell / CALmatters

Butt says one big reason is that costs for employees’ retirement benefits keep climbing. The city’s finance director said in an email that over the next five years, Richmond’s pension costs are projected to jump almost 40 percent.

Mayor Butt said that’s hard in a city that’s much poorer than neighboring communities such as El Cerrito, which has a median household income of about $94,000 compared with about $56,000 in Richmond, according to Census data. Butt said that makes it tougher to generate tax revenue in his community.

He blames the California Public Employees Retirement System, or CalPERS, which is the agency that manages his city’s pensions.

“They base payments the city has to make on the pension plan… on their projected future returns, and they’ve consistently been adjusting their returns downward, which means the city’s payment goes upward,” Butt said.

CalPERS pays out pension benefits to retirees through a combination of returns from stocks, bonds and other investments, local government contributions and employee contributions. But when the stock market tanks, as it did during the Great Recession, retirees still get the same benefits and employers like the city of Richmond have to make up the difference.

Richard Costigan, a CalPERS board member, said it’s unfair for cities like Richmond to pin the blame on the agency that administers their pension plans.

“At the end of the day, local governments in the state of California made promises to their employees and we have to fulfill those promises,” Costigan said.

Costigan said local governments and their public sector unions are the ones that set the level of benefits, not CalPERS. He said his agency knows that big jumps year to year can cause difficulties for city budgets, but he said CalPERS has had to ask cities to contribute more, because, for example, life expectancy has gone up.

“People are living longer, okay? Well, as we live 72, 74, 75 years, those liabilities grow out,” Costigan said.

Richmond Mayor Tom Butt said the city reached agreements with several of its unions last year for members to pay more toward retiree health care. And Benjamin Therriault, president of the Richmond Police Officers Association, said his members began making larger pension contributions in 2013.

“Everyone wants to pin it all on the employees and the unions,” Therriault said. He argued that it’s more of a revenue-generation problem and that city leaders have failed to attract development that could add to the city’s tax base.

Still, cities such as Richmond will have more tough choices ahead as they figure out how to pay for workers’ retirement benefits and keep city services stable.

Mayor Butt had hoped voters would approve an increase in the real estate transfer tax in the November election to bring in more money, but more than 70 percent of voters said no.

California Pension Crisis: Richmond

Wednesday, February 8, 2017

How are cities across California responding to the ballooning cost of pensions in the state? CALmatters Reporter Judy Lin explores a case study in Richmond where priority police and library services are already being cut.

|

|