|

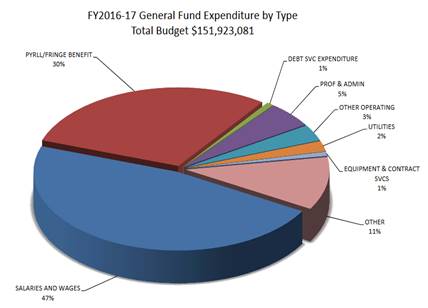

| I strongly disagree that the City of Rchmond is “the state’s most likely candidate for insolvency,” but it is true that $46 million (30%) of Richmond’s $151,923,081 General Fund goes for Pension and OPEB benefits, and these are headed nowhere but up.

There are also dozens of non-General Fund accounts where the City is responsible for pension and OPED payments amounting to another $10 million that are also going nowhere but up, and the City is still responsible for them.

When I was quoted as saying “It’s a huge mess. I don’t know how it’s going to get resolved. One of these days, it’s just going to come crashing down,” I was referring to the entire state, not just Richmond.

How fast Richmond’s benefit payments rise is ultimately under control of the City Council. I don’t know if the prediction of “another 50% rise” in the next five years is accurate, but we should be looking at it in the next iteration of our 5-Year Budget Model, due out soon.

Here is a good article on the subject from a national stanpoint: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/americas-utterly-predictable-tsunami-of-pension-problems/2017/02/22/1e5de00e-f869-11e6-9845-576c69081518_story.html?utm_term=.78361e237282.

Tom Butt

Cities, counties and schools feel sharply increasing pension costs

By Dan Walters

dwalters@sacbee.com

The impact of ever-higher pension costs on California’s local governments, particularly cities, has been evident for years.

Pension burdens contributed to the recent bankruptcies of three cities and more are feeling the pinch.

The California Public Employees’ Retirement System, or CalPERS, is ramping up its mandatory contributions to offset investment losses in the Great Recession, its subpar investment earnings more recently, and actuarial projections that retirees will live – and collect pensions – for longer periods.

Municipal finance analysts see Richmond, an industrial city on San Francisco Bay, as the state’s most likely candidate for insolvency, largely due to sharp increases in pension fund contributions to cover its police and fire personnel.

Richmond is spending nearly $50 million a year now for its pension and retiree obligations, 50 percent more than what it was spending six years ago, and anticipates another 50 percent increase in the next half-decade.

“It’s a huge mess,” Richmond Mayor Tom Butt told CALmatters, a nonprofit news organization. “I don’t know how it’s going to get resolved. One of these days, it’s just going to come crashing down.”

Richmond, like most cities, ramped up its pension benefits after the state Legislature and then-Gov. Gray Davis did it for state workers in 1999 on assurances from CalPERS that its investment earnings, rather than taxpayers, would cover the added costs.

Facing sharply rising pension costs, many local governments have sought tax increases from their voters, characterizing them as improvements to “public safety” without mentioning that much of the extra money would go to CalPERS.

Madera County, for example, is asking voters in unincorporated communities next month for a 1 cent increase in the sales tax, promising to improve fire protection and sheriff’s patrols with the proceeds.

However, data from the county budget and CalPERS indicate that much of the extra revenue would go for pensions. By next year, the county will see its “safety system” pension outlays double to more than $3 million a year in just four years.

Nor is the pension squeeze confined to cities and counties. School districts also are getting hit with big pension payments, not only from CalPERS for their non-teaching personnel but from the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, or CalSTRS, under a plan that Gov. Jerry Brown and legislators adopted to shrink its unfunded liabilities.

The state and teachers themselves are pumping more money into CalSTRS, but the big hit is on school districts, which will see their contributions rise from 8.3 percent of payroll in 2013-14 to 19.1 percent by 2020-21.

The hits from CalPERS and CalSTRS will cost school districts $1 billion more next year, the Legislature’s budget analyst has calculated, markedly more than the $744 million in additional state and local revenue Brown’s budget proposes.

San Diego Unified, the state’s second largest school district, cites rising pension costs and declining revenue from declining enrollment in declaring that it faces a more than $100 million deficit that will require layoffs and other cuts to close. It has nearly exhausted its reserves after several years of operating deficits.

With the pension cost squeeze hitting home, local government and schools are looking at a pending state Supreme Court case for potential relief. If the court upholds appellate court rulings, they may be empowered to reduce future pension benefits, or at least seek reductions in contract negotiations.

Read more here: http://www.sacbee.com/news/politics-government/politics-columns-blogs/dan-walters/article134832779.html#storylink=cpy |

|