|

| This is a really good article on rent control, whose advocates have a lot in common with climate change deniers. It has been widely reported that 97 percent of informed scientists who have an opinion agree that global warming is real and that it results from human activity. In a survey of respected economists, the percentage of those having an opinion that rent control doesn’t work was even higher at slightly over 97 percent.

In 2013, Peter Tatian of the Urban Institute reviewed academic research on rent control and found “very little evidence that rent control is a good policy.” The strongest finding of one comprehensive survey was that “tenants in noncontrolled units pay higher rents than they would without the presence of rent control; one reason being that landlords need to make up the difference for lower rents in controlled units.”

Rent control “puts the burden of housing affordability on the backs of a few people,” said Christopher Palmer, assistant professor of real estate at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “It’s a way to say housing is unaffordable, we want to help so we are going to stick it to the man — absentee landlords with tons of capital. It’s not clear they should be the ones having to pay for the affordability mess we are in,” Palmer said.

Or even that they will. Essex Property Trust, based in San Mateo, is a publicly traded company that owns many large complexes in the Bay Area. In a call with analysts last month, its CEO said that rent-control measures “will have limited impact on Essex, primarily because the vast majority of our properties are newer than the rent-control cut-off dates.” He added that renewals at below-market rates are “partially mitigated by higher rents on new leases, reflecting the unintended secondary effect of rent control.”

Palmer pointed out that not all landlords are rich. He knows a couple in Oakland — a public school teacher and his wife — who own rent-controlled apartments occupied by tenants who earn more than they do.

Rent control advocates will try to jump start the measure on the November ballot with a proposed moratorium that will fail for lack of votes.

See the article at http://www.sfchronicle.com/business/networth/article/Rent-control-spreading-to-Bay-Area-suburbs-to-9215216.php?t=a4cbc1c50f, and copied below.

Tom Butt

Rent control spreading to Bay Area suburbs, to economists’ dismay

By Kathleen Pender

September 10, 2016 Updated: September 10, 2016 11:20pm

Photo: James Tensuan, Special To The Chronicle

Diane Fjelstad backs a San Mateo ballot measure after she saw her rent increase by $1,000 a month.

The concept of rent control, once found mostly in large cities, is spreading to the Bay Area’s suburbs, even though virtually every economist thinks it’s a bad idea.

Six Bay Area cities have measures on the November ballot that would protect existing tenants from the stratospheric rent increases that are a result of job growth far outstripping housing creation.

In San Mateo, Burlingame, Mountain View, Alameda and Richmond, voter initiatives would establish rent and eviction controls.

In Mountain View and Alameda, voters will face dueling ballot measures — the voter initiative and another placed on the ballot by their respective city councils that would continue the mediation and arbitration programs that each city started this year to hear disputes over rent increases exceeding certain amounts. In Oakland, the City Council placed a measure on the ballot to make its existing Rent Adjustment Program more favorable for tenants.

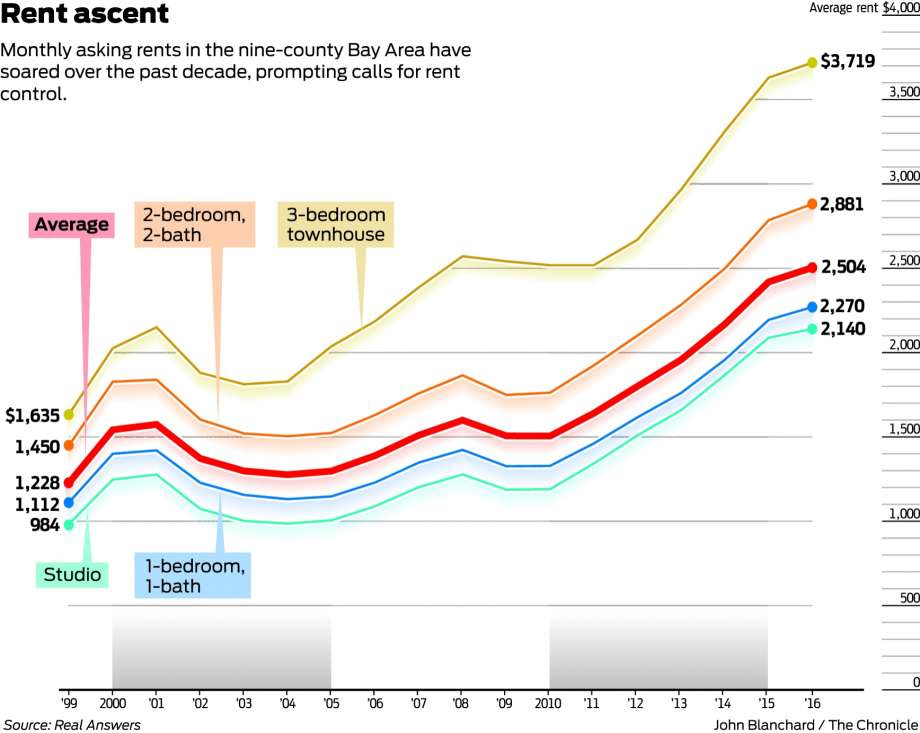

Since 2010, the average asking rent for units of all sizes in the nine-county Bay Area has risen by roughly $1,000, or 66 percent, to $2,504, according to Novato research firm Real Answers.

“The rent crisis is tearing apart our communities, displacing people up and down the economic ladder and uprooting them from, in some cases, decades of living in the community,” said Jennifer Martinez, executive director of Faith in Action Bay Area, which sponsored Measure Q in San Mateo.

Diane Fjelstad said she helped gather signatures for Measure Q after her new landlord raised the rent on her two-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment in a family-owned building near downtown San Mateo from $1,850 to $2,850 a month in October. Her previous landlord had not raised the rate since she took up residence in 2002, and actually reduced it when Fjelstad’s daughter turned 18 and she lost child support.

Fjelstad was expecting a rent increase when the landlord died and another family member took over, but not $1,000. “I’m a retired psychiatric worker, living on a (state) pension. I’m 63 years old and have a daughter living with me who is working full time. To pay the additional rent, I took out Social Security early,” Fjelstad said. “Because we don’t have renter protections, if he raises the rent again, I will be displaced. I’m already cost-burdened, with about 35 percent of my income going to rent.”

Economists are sympathetic but say rent control is unfair. In California, it helps incumbent tenants in rent-controlled units but does nothing to encourage housing creation.

A 2012 survey by the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business asked respected economists if they agreed that rent-control ordinances in cities such as New York and San Francisco have improved the quantity and quality of affordable rental housing over the past three decades. Eighty-one percent disagreed, 2 percent agreed and 9 percent were uncertain or had no opinion.

In 2013, Peter Tatian of the Urban Institute reviewed academic research on rent control and found “very little evidence that rent control is a good policy.” The strongest finding of one comprehensive survey was that “tenants in noncontrolled units pay higher rents than they would without the presence of rent control; one reason being that landlords need to make up the difference for lower rents in controlled units.”

Rent control “puts the burden of housing affordability on the backs of a few people,” said Christopher Palmer, assistant professor of real estate at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “It’s a way to say housing is unaffordable, we want to help so we are going to stick it to the man — absentee landlords with tons of capital. It’s not clear they should be the ones having to pay for the affordability mess we are in,” Palmer said.

Or even that they will. Essex Property Trust, based in San Mateo, is a publicly traded company that owns many large complexes in the Bay Area. In a call with analysts last month, its CEO said that rent-control measures “will have limited impact on Essex, primarily because the vast majority of our properties are newer than the rent-control cut-off dates.” He added that renewals at below-market rates are “partially mitigated by higher rents on new leases, reflecting the unintended secondary effect of rent control.”

Palmer pointed out that not all landlords are rich. He knows a couple in Oakland — a public school teacher and his wife — who own rent-controlled apartments occupied by tenants who earn more than they do.

Likewise, rent control protects high-income tenants as well as working-class ones. “Not one of these rent-control measures on the ballot have any means testing. You can be making $150,000 a year, and if you are in a rent-controlled unit, you are never going to leave. All of a sudden there is no trickle effect. No working-class family will ever get that unit,” said Thomas Bannon, CEO of the California Apartment Association, which represents landlords.

In a report issued in February, California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office warned that rent control could encourage property owners to cut back on maintenance and repairs. “Over time, this can result in a decline in the overall quality of a community’s housing stock,” it said.

Juliet Brodie, who directs the Stanford Community Law Clinic and helped draft what became Measure V in Mountain View, acknowledges that rent control, like any public policy, has shortcomings. “What it prevents is landlords evicting moderate-income tenants and replacing them with people paying twice as much,” she said. “I would be perfectly happy to tolerate lucky Google employees who decided to lease up at the right time and have $1,700 (a month) rent to protect families who are being kicked out in the middle of the school year.”

To understand the arguments for and against these measures, it helps to understand how rent control works in California.

In cities without rent control, landlords can charge whatever the market will bear, raise the rent when the lease is up and evict tenants for any reason, with proper notice.

Cities with rent control typically limit not just annual rent increases (which is what most people think of as rent control). They also restrict the circumstances under which landlords can evict tenants, even when their lease is up, to certain “just causes,” such as nonpayment of rent and criminal activity on the property. In these cities, landlords must go to court to prove just cause and get a judgment to evict them, Bannon said.

If a city only limited rent increases, landlords could simply evict tenants when their lease is up and charge the next one market rates.

Two state laws place some limits on both rent control and eviction control.

The Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act exempts multifamily apartments built after Feb. 1, 1995 — and all single-family homes and condos, whenever built — from limits on rent increases. It also said that when tenants voluntarily vacate a rent-controlled unit, owners can charge the next tenant market rates, but after that it becomes subject to the annual rent control limit.

Costa-Hawkins does not prevent cities from imposing eviction controls on any type of rental housing — including single-family homes and apartments of any age. That allows cities to limit evictions to specified just causes, including those allowed under a 1985 law known as the Ellis Act.

The Ellis Act says cities cannot prevent owners from evicting tenants from a unit so the owner or a family member can move in. Nor can they prohibit owners from evicting all tenants from a building so they can go out of the rental business. However, cities can impose certain rules on Ellis Act evictions and require landlords to compensate tenants, up to a limit, who are displaced under the law.

All of the rent-control measures on the November ballot exempt multifamily homes built after February 1995 and single-family homes from price controls, as required by law. Some of these measures also exempt single-family homes and newer condos from eviction controls.

Whether these measures can get the simple majority needed to pass could depend on the percentage of households that rent in each city, Palmer said. According to 2014 U.S. Census Bureau data, renter percentages were about 45 percent in San Mateo, 52 percent in Burlingame, 53 percent in Alameda, 55 percent in Richmond, 60 percent in Mountain View and 61 percent in Oakland.

Owners and renters wondering how the measures would affect them should read them carefully before casting a vote.

Kathleen Pender is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist. Email: kpender@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kathpender

Rent-control proposals on November ballots

Burlingame

Measure R. Voter initiative. Limits rent increases on pre-1995 multifamily buildings to the Consumer Price Index increase (but not less than 1 or more than 4 percent). Establishes just-cause eviction rules for all rental property including single-family homes, condos and multi-family units, whenever constructed.

San Mateo

Measure Q. Voter initiative. Limits rent increases on pre-1995 multifamily buildings to CPI increase (but not less than 1 or more than 4 percent). Establishes just-cause eviction rules for all mutlifamily units constructed before the measure takes effect. Single-family homes and condos exempt from rent and eviction control.

Mountain View

Measure W: Placed on ballot by City Council. Would amend rent program that the city started in April to require binding arbitration for rent increases exceeding 5 percent on pre-1995 buildings. Also limits evictions to just causes, unless landlord complies with the city’s Tenant Relocation Assistance Ordinance.

Measure V: Voter initiative. Rolls back rents on pre-1995 multifamily units to October 2015 levels, limits future increases to CPI increase (but not less than 2 or more than 5 percent). Limits evictions on multifamily units constructed before the measure takes effect. Exempts single-family homes and condos from rent and eviction controls.

Alameda

Measure L1: Placed on ballot by City Council. Would continue program that the city started in March that requires mediation on increases above 5 percent (mediation is binding only for multifamily homes built before February 1995) and limits evictions on all rental property.

Measure M1: Voter initiative. Rolls back rents on pre-1995 multifamily buildings to May 2015 levels and limits future increases to 65 percent of the CPI increase. Establishes eviction controls on all rental property, including single-family homes, condos and multifamily units built since 1995.

Richmond

Measure L: Voter initiative rolls back rents on pre-1995 multifamily apartments to July 2015 levels and limits future increases to the CPI. Imposes eviction controls on all rental units.

Oakland

Measure JJ: Placed on ballot by City Council. Would amend Oakland’s Rent Adjustment Program. Requires owners of multiunit apartments built before Jan. 1, 1983 to get city approval before raising rents by more than the CPI increase. Also extends just-cause eviction protections to buildings constructed through Dec. 31, 1995; existing cutoff is Oct. 14, 1980.

Note: Find links to the full ballot measures and analyses in the online version of this story at www.sfchronicle.com. |

|