|

| Andrew,

I am very disappointed in your recent piece about Richmond. Both Richmond and KQED deserve better.

First of all, you can find a Gail Anderson anywhere who will complain about anything. Why is this news, and why Richmond?

Seeking out Jack Weir of the Contra Costa Taxpayers Association for a quote on taxes is like asking Donald Trump for an objective opinion on Mexicans. About taxes, Weir wrote in his “Political Philosophy” when running unsuccessfully for City Council in Pleasant Hill, “Direct and indirect taxes (of all kinds) now constitute the largest segment of working families' budget; this is wrong and unsustainable.” Weir never met a tax he liked.

Every city has problems, challenges and issues, including Richmond. Richmond, however, happens to be the second poorest of 101 cities in the Bay Area, ranked only above San Pablo in median family income. We struggle, and we have to be creative and perhaps work harder than any other city to provide our residents with a decent quality of life. I don’t understand why some reporters, like you, think that beating up on Richmond is great news.

We do have plenty of real news in Richmond, but it’s different from what you are reporting. If you want to pick on someone, take a look at the many cities that are not taking care of business as well as Richmond.

For example, despite its relative poverty, Richmond has disappeared from the list of the ten most dangerous cities in the U.S. and in California. Those Bay Area cities that remain on the latest list of California’s ten most dangerous cities, include Stockton (2), Vallejo (4), Oakland (6) and Antioch (7). We believe that one of the reasons is that when many cities cut their police budget during the recession, Richmond did not. Now there’s a story.

Take a look at the Pavement Condition Indices for Bay Area Cities and Counties at http://mtc.ca.gov/our-work/fund-invest/investment-strategies-commitments/fix-it-first/local-streets-roads/2014-pci. Richmond is rated “Fair,” but is higher than 35 cities and counties, including wealthy places like Orinda and Mill Valley. How can the Bay Area’s second poorest city have better streets than Orinda? There’s another story.

The only thing you actually got right was my explanation about how Measure U morphed from an effort to increase funding for street repair to a general tax.

You intimated that there was some sort of deception. You wrote “All of the money raised through the tax has gone straight into the city’s general fund,” like that was some bait and switch. Measure U was balloted as a general tax, not a special tax. In fact, money from the measure was required by law to go into the general fund and not to be used for any specific purpose.

You also wrote, “the California State Controller’s Office briefly opened an investigation into the city’s finances.” The California State Controller’s Office did not “open an investigation.” They actually declined to open an investigation after meeting with the city manager and me and taking a closer look at Richmond’s finances.

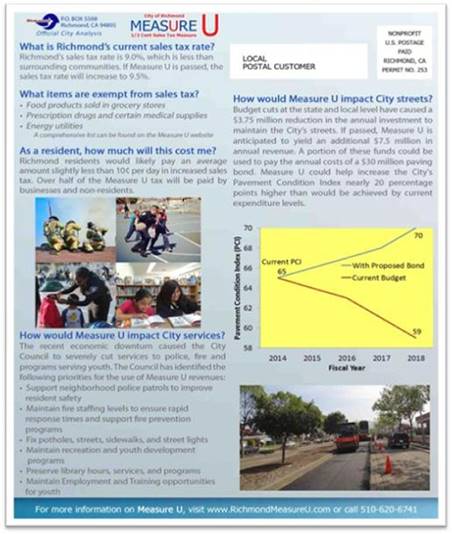

You included an informational piece from the City about Measure U. It does not commit Measure U funds exclusively to streets; it lists a number of different potential uses, including streets.

"A portion of these funds could be used to pay the annual cost of a $30 million paving bond. Measure U could help increase the city’s pavement condition index early 30 percentage points higher than would be achieved by current expenditure levels."

The actual title for Measure U that appeared on the ballot contained 36 words, only two of which mentioned “street paving.”

"Shall the City of Richmond adopt a one-half cent transactions and use (sales) tax, to fund and maintain essential city services, such as public safety, public health and wellness programs, city youth programs and street paving?"

In fact, the first year’s proceeds from Measure U were used for all these things (“essential city services, such as public safety, public health and wellness programs, city youth programs and street paving”). The budget for street maintenance in this current budget year (FY 2015-16) was substantially increased from FY 2014-15. You could have looked at the budget (http://www.ci.richmond.ca.us/DocumentCenter/View/34458) and found, for example, that the number of “city blocks resurfaced” rose from 80 to 96, and the number of potholes filled from 2,100 to 3,000. The Pavement Condition Index (PCI) was projected to rise from 62 to 63. The only thing the City did not do, with an abundance of caution, was to immediately float a bond for street repairs that would have tied up Measure U revenue for many years to come.

Please, if you are going to report on Richmond, do it accurately and objectively.

Tom Butt, Mayor

False Promises of Fixed Streets in Richmond?

A pothole-filled street in Richmond. (Andrew Stelzer/KQED)

By Andrew Stelzer May 31, 2016

Gail Anderson is driving around her Richmond neighborhood, checking out all the best spots — for potholes. She says they’re actually not very hard to find.

“See these cracks in here. … A whole line just tore up. … They go anywhere from 2 to 3 inches deep,” Anderson explains, as she swerves to stay on flat ground.

Anderson is frustrated about the state of the streets, but she’s even more upset about the mattresses, furniture and other trash piled up on the sidewalks, and a tree branch that fell on her house last year — she’s afraid the whole tree will fall soon. On all of these issues, the city has not given this life-long Richmond resident the help she thinks citizens deserve.

“They’re not taking care of the citizens of this city. The graffiti, the holes in the road, the dumping which is just outrageous. It just makes the city look unclean, “ says Anderson.

Gail Anderson and a pothole in front of her house. (Andrew Stelzer/KQED)

“This is embarrassing to me that we can’t keep our city together. They call it a city of pride and purpose, but it’s pathetic and pitiful to me,” she added.

Although Richmond’s crime rate has significantly improved in the last few years, it’s not necessarily sharing in the Bay Area’s economic boom. New businesses have been slow to invest, and wealthy newcomers have been gravitating toward other East Bay cities, like Berkeley and Oakland.

In 2014, Richmond came up with a potential new revenue source: a half-cent sales tax called Measure U. In informational mailers paid for by the city, Measure U was promoted as a way to help fund improvements to roads, as well as public safety and youth programs. However, Mayor Tom Butt says it didn’t quite turn out as planned.

“Measure U was actually born with the idea that it would provide additional revenue, some of which could be used for streets. And as it developed, we came to realize that it probably wasn’t all gonna be used for streets,” Butt explained.

All of the money raised through the tax has gone straight into the city’s general fund. The way the initiative was worded, that’s completely within the law. But Jack Weir, president of the Contra Costa Taxpayers Association, said it’s a bad way to run city government.

“The whole controversy about Measure U. It’s not just about that they didn’t use the money the way they said,” said Weir.

A 2014 election season mailer, touting how Measure U would improve Richmond’s streets and other city services.

“If the roads aren’t properly maintained over time, taxpayers wind up having to pay way more to keep the infrastructure capable of fulfilling its expected useful life. And that’s bad management, both from a policy perspective and from a fiscal perspective,” he added.

Richmond is in a tough place. It’s been facing budget deficits for years. Last year Moody’s downgraded Richmond’s bond rating, and the California State Controller’s Office briefly opened an investigation into the city’s finances. To try and keep its financial reputation afloat, the city’s 2016-17 draft budget again routes all the Measure U revenue, almost $8 million, into the city’s general fund. Nothing is earmarked for streets.

Richmond City Manager Bill Lindsay admits no one is tracking how the Measure U money is being spent, but says, “The Measure U story really isn’t done yet.”

Lindsay says population growth should lead to more sales tax revenue in the next few years, which could free up the City Council to fund things that the Measure U campaign promised.

“Two, three years, four years down the road, looking back, I expect our pavement condition index is going to be better, and my hope is that the voters feel like it was a good investment,” said Lindsay.

But in the meantime, there may be more new taxes coming soon. Mayor Butt is pursuing a hike in the city’s real estate transfer tax and a “litter” fee on cigarettes, to appear on the November ballot. Both of those pots of money, he says, would go to the general fund as well. |

|