| |

All lives matter' a creed for Richmond, Calif. police

Chris Magnus, police chief in Richmond, Calif., discusses the methods he and his force have used to reduce crime in the city. He also explains his controversial choice to hold a sign reading "#blacklivesmatter" at a December 2014 rally. Martin Klimek, USA TODAY

Elizabeth Weise, USATODAY 7:21 p.m. EDT September 23, 2015 Elizabeth Weise, USATODAY 7:21 p.m. EDT September 23, 2015

(Photo: Martin E. Klimek, USA TODAY)

7 CONNECT 32 TWEETLINKEDIN 3 COMMENTEMAILMORE

RICHMOND, Calif. — In a town that once had one of the highest per capita homicide rates in the nation, Capt. Bisa French can't find any law-breakers.

“It just trips me out,” the 17-year veteran police officer said during a morning drive around this somewhat gritty city 11 miles north of Oakland.

It’s too strong a statement to say Richmond is an anti-Ferguson. Perhaps it’s better to say Richmond could have become Ferguson, including the possibility of ongoing discord and violence, had several remarkable things not happened.

One of those things was the hiring nine years ago of Chief of Police Chris Magnus. A white, gay man in a police force and a town with histories of racial tension, he came to Richmond after six and a half years as police chief in Fargo, N.D., and spent most of his career in Lansing, Mich.

Magnus, 54, has been catalyst of a remarkable change, but he is by no means the sole cause. The community and the police have come together in Richmond to turn a town where no one talked to the police — for fear of being called a snitch — into a place where residents collect their beat cops’ cell numbers and dance with them at street festivals.

USA TODAY

Policing the USA: A look at race, justice and media

Most importantly, Richmond is a city where the small-town ethos older residents remember is again visible as the violence that masked it for so long loosens its grip.

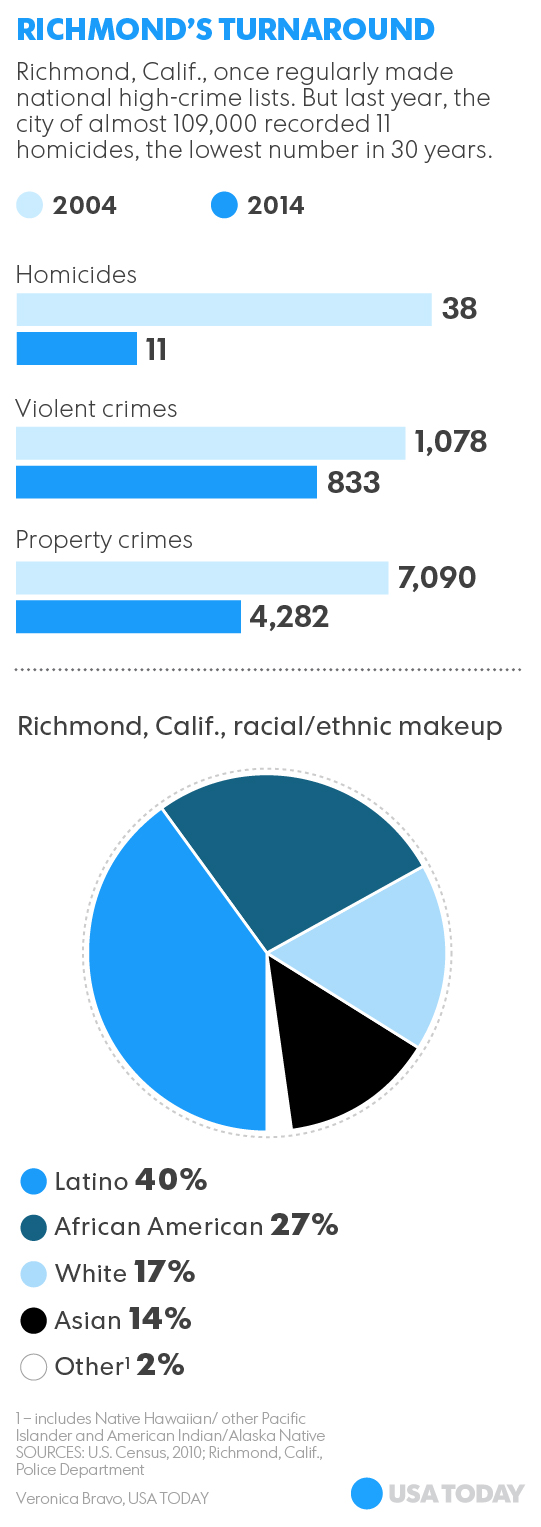

In 2004, Richmond had 38 homicides, 1,078 violent crimes and 7,090 property crimes. By 2014, those numbers were down to 11,833 and 4,282, respectively.

“We used to just run from call to call to call,” French said. Today, the city of 110,000 is calmer, and crime is less frequent. Officers’ jobs are more about finding and fixing the roots of the problems they encounter and less about hauling in miscreants, dumping them in jail, then going out to find more.

Though Magnus has helped guide Richmond’s transformation for years, he came to national attention last December just for holding up a piece of cardboard.

Magnus and some of his command staff were at a community center in town where a peaceful protest was underway over the shooting of Michael Brown by police officer Darren Wilson in August 2014 in Ferguson, Mo.

One of the protesters asked him to hold a sign that read #BlackLivesMatter Though he realized it had the potential to be controversial, Magnus took the sign. It was the right thing to do, and “I would do it again,” he said.

Photos of the chief holding the placard went viral. Magnus is prouder of the years of work put in before that moment, time that created a climate where the protesters felt comfortable handing him the sign in the first place.

BACK TO THE BEAT

When stories about police brutality and racial strife seem to occur every day, Richmond is a poster city for the power of community policing. Magnus has reinstituted beats and required officers to build relationships with people in the areas they patrol.

“If you solve the repeat calls, guess what? You’re less busy, and you have more time to solve the problems,” Assistant Chief Allwyn Brown said.

Richmond, Calif., police captain Bisa French, photographed during an interview with USA TODAY at the police station on Friday, August 7, 2015, is surprised to find few law-breakers in the city nowadays. (Photo: Martin E. Klimek, USA TODAY)

Making that human connection pays off. On Sept. 12, a man wanted on serious domestic violence charges barricaded himself inside a house, with weapons. The situation had the potential to become very dangerous, and the SWAT team was called out.

Then something extraordinary happened. One of the officers knew the man and asked his mother to call him and get him to come to the door to talk. Instead of a firefight, the two talked at the door, and the man walked out of the house.

“It ends with no shooting and no deaths and no big drama,” Magnus said. That, he said, is the power of relationships.

All of this is a far cry from the bad-old days. In 2005, a wave of shootings caused some City Council members to suggest declaring a state of emergency. A city councilwoman called part of Richmond “a war zone.” In 2007, it was the ninth-most dangerous city in the USA per capita.

People “got to the point where they said, ‘Enough is enough!’ ” said Richmond native Bennie Singleton, who describes herself as “in my 70s.”

The community came together, demanding better policing, better oversight and better government. Magnus’ hiring was both an emblem of change that had already begun and an impetus for more.

It was part of multiple city initiatives working to get at the roots of the violence. Another is Richmond Ceasefire. Each Friday night, residents walk through the neighborhoods as an expression of their concern and care for the communities they live in.

That strong connection to city leadership is one thing that distinguishes Richmond from Ferguson, said Laurie Robinson, a professor at George Mason University and co-chair of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. “One of the things that was missing in Ferguson was that I don’t think people there even felt they would be heard if they protested. If people are unhappy in Richmond, they know who to talk to, and they know they’ll be listened to.”

USA TODAY

California asks: where have all the cops gone?

Richmond lies on San Francisco Bay. Founded in the 1890s, it quickly became a prime manufacturing and shipping hub. During World War II, it was a boomtown, site of the Kaiser Richmond Shipyards, one of the largest shipbuilding operations on the West Coast.

The city became home to a large African-American population as workers streamed there from the South. In the 1970s, the city began a major economic decline as manufacturing jobs were lost. By the 1980s, it had become a violent, crime-ridden city with what some called an out-of-control police department.

Although the town was almost 50% African American, the police department was mostly white. There were even separate police officers groups, one for white officers and one for black.

In 1983, a federal jury awarded $3 million in damages to the families of two African-American men slain by police. The suit castigated the city for tolerating a group of brutal, violence-prone officers on the night shift, called “The Cowboys.”

“It was very bad for people of color in this city,” said Naomi Williams, 83, who, like Singleton, grew up in the city.

A PLACE TO START

Despite troubles with policing and crime that spilled into the 2000s, the old-school vibe was still there. Richmond “has a very friendly, Southern kind of love to it,” said Richard Boyd, 60. “This is a place where, when my wife goes out of town, people feed me.”

The community began asking for more from their city leaders. They wanted leaders who would engage and work with them.

Richmond, Calif., Chief of Police Chris Magnus stands with demonstrators on Dec. 9, 2014 along Macdonald Avenue to protest the Michael Brown and Eric Garner deaths. The Northern California police chief, noted for his community policing efforts, raised a few eyebrows when he joined a peaceful protest, holding a sign with the popular Twitter hashtag of "blacklivesmatter." (Photo: Kristopher Skinner, Associated Press)

In 2005, Williams was part of an interview process to hire a police chief. She knew right away Magnus was special.

He stood out during the first meet-and-greet: Whereas most of the candidates “waited around for somebody to ask them questions,” Williams said, “he approached us. Not everybody did that.”

When Magnus took the job, it was as if a shift that had started deep underground began to rise to the surface and become visible.

“He came in like a storm,” Singleton said. He even bought a house in Richmond, something his predecessors hadn’t. “That was a first,” she said.

COMMUNITY FIRST

It’s hard to find a community event without Magnus or at least one or two of his officers. “If the community wants him to attend, he will. No excuses,” Williams said.

In his office, Magnus proudly shows off pictures of his officers hanging out at community BBQs and block parties and showing off their dance moves.

On a recent Monday night, he was at a neighborhood council meeting, “and all the neighborhood presidents were arguing about who had the best dancing cops at their parties,” he said.

“YouTube Andrew Barbara doing The Wobble!” he orders a reporter, who found it by searching YouTube for Juneteenth Richmond 2014.

Richmond, Calif. Chief of Police, Chris Magnus, 54, is photographed with Assistant Police Chief Allwyn Brown, right, during an interview with USA TODAY at the police station on Friday, August 7, 2015. Brown favors Magnus' problem-solving approach to policing. "If you solve the repeat calls, guess what? You're less busy and you have more time to solve the problems," Brown said. (Photo: Martin E. Klimek, USA TODAY)

Residents say they’re in partnership with the police. Once officers ignored his calls, Boyd said. Now, they “actually give out their cellphone numbers to the residents,” he said.

Magnus has worked especially hard to get Richmond’s immigrant community to work with the police. Latinos make up at least 40% of the city. The African-American population is at about 27%, whites at 17% and Asians 14%.

Zara Fierra, 24, came to the USA from Mexico when she was 9. As undocumented immigrants, her family feared any interaction with the police. “You were afraid that anything could lead to deportment,” she said.

To her surprise, she’s got a “friendship connection” with police. She’s even run into Magnus at Costco and in the park with his dog and husband. “Things like that really make Richmond feel like a tightknit community,” Fierra said.

STAYING PUT

One reason Magnus has been able to make major changes in his department is simply that he’s had time to, Robinson said.

Most police chiefs spend three or four years on the job before they move on, often when a new city government comes in. That allows some officers to dig in their heels and avoid change.

Magnus has had nearly a decade to remake his force, serving largely under Gayle McLaughlin, who was mayor from 2007 to 2015 and who sits on the City Council.

About 12 officers who were there when he first arrived remain, French said.

“We’re very picky. People know the reputation of our department,” Magnus said.

‘SO GOOD IT'S PITIFUL'

The shift isn’t happening just in Richmond, said Jim Bueermann of the Washington-based Police Foundation. He ticked off several cities doing the same kind of community-based policing, including Los Angeles, San Diego, Minneapolis, Austin, Draper City, Utah, and Los Gatos, Calif.

They just don’t get media attention. “Where things are working well, there is less of a spotlight because the attention now is focused on problems,” Robinson said.

Word is getting out about Richmond. Singleton is thrilled that the town she loves is coming back into its own. “Eighty percent of the people in Richmond are so good, it’s pitiful,” she said.

| |