| |

Leaving his life as a poor farm worker from a large family in a remote village in Mexico, Guadalupe Campos emigrated to the U.S. in 1965 and found work as garbage truck driver in San Francisco. He worked hard for many years, saved his money and invested in a couple of rental properties in the Mission District, then San Francisco’s poorest neighborhood.

His son, Eddy Campos, followed his father into the garbage business, also driving a garbage truck for Recology, San Francisco’s waste management company. Eventually, the elder Campos retired, and the family moved from Daly City to Millbrae. In 2002, Guadalupe Campos bought two identical apartment buildings in Richmond, 1220 and 1300 Bissell Avenue, with 20 units each, to help provide retirement income, and depended on his son, Eddy, to help manage and maintain them on nights and weekends.

Not too long after the Campos acquired the Richmond Buildings, the Great Recession hit, driving down both rents and occupancy, as well as property values, and making cash flow a challenge. More than once, the Campos found themselves pulling money from their savings just to keep the apartment buildings afloat. Deferring essential maintenance was not an option because the City of Richmond routinely inspects rental apartments to make sure they are livable and up to code.

For a time during the recession, the Contra Costa County Assessor lowered the appraised value, giving some property tax relief, but now assessments have been raised again. Eddy told me his father had recently pulled $10,000 from savings to pay property taxes. Meanwhile, utility costs, which the landlord pays, continue to rise. Last year the Campos’ had to spend $30,000 on a new roof. Until recently, rents at 1200 and 1300 remained substantially below market, and the buildings are at full occupancy. Last month, the Campos finally needed to raise rents to protect their investment and stabilize their cash flow, and they did, typically 20%, with the rent for a 2-bedroom apartment going from $1,000 to $1,200.

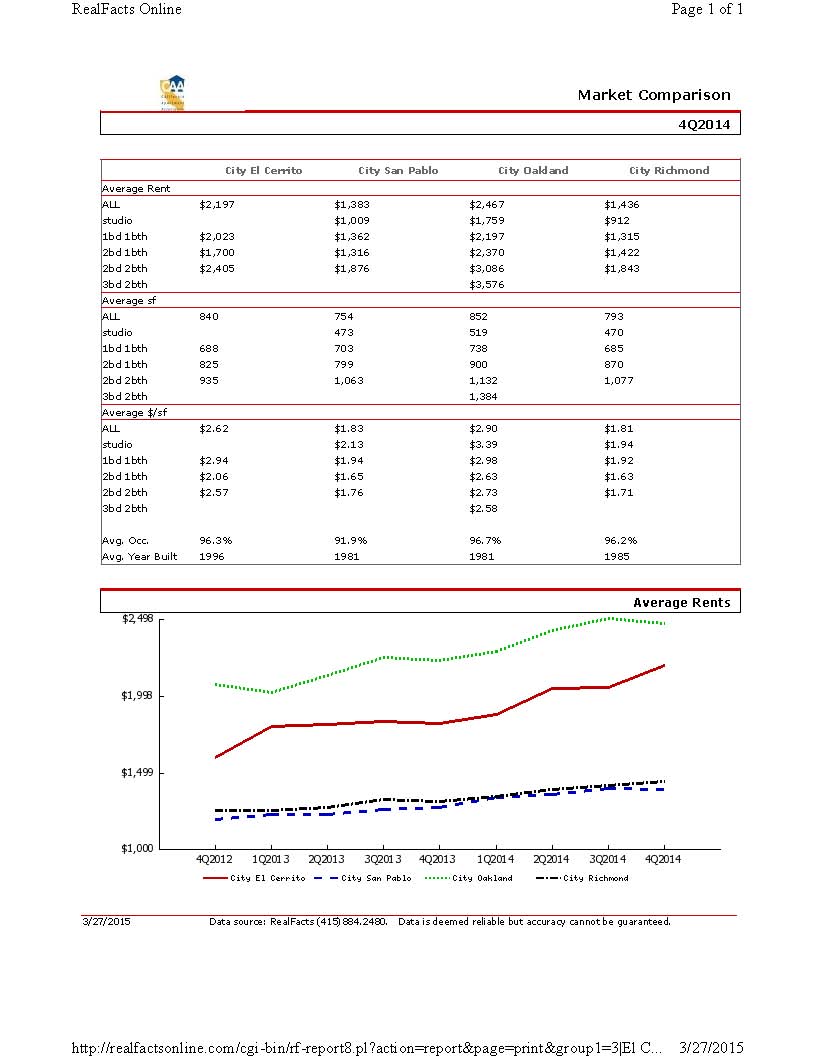

That may sound like a lot, but at the end of 2014, the average rent for a 2-bedroom apartment in Richmond was $1,422, and the average size was 870 square feet. The apartments at 1200-1300 Bissell are over 1,000 square feet and even at the new $1,200 rate are 17% below where the market was three months ago.

Most of the renters at 1200-1300 Bissell are, themselves, immigrants, many undocumented and doubling and tripling up with others to lower their housing costs. Most of them like renting from Campos because he speaks their language and understands from experience what it is to be a struggling immigrant.

This sounds like a great success story about an immigrant family who found the American dream and is helping the next generation of immigrants establish themselves. It is that, but it is also a cautionary tale.

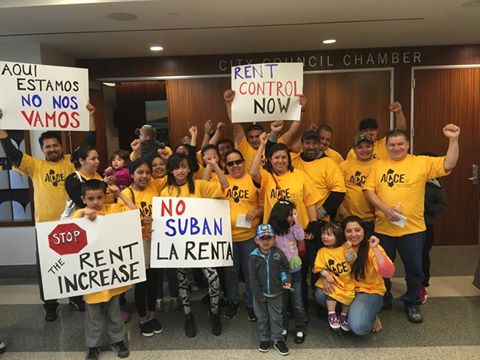

What did the Campos get for their efforts? Their reward was a crowd of ACCE members picketing their home in Millbrae and packing the Richmond City Council Chamber, labeling the Campos as “abuser”s and making 1200-1300 Bissell the poster child for rent control in Richmond.

They were also accused of “bad conditions” in their building, despite that fact that the City of Richmond inspects rental units regularly and gave 1200-1300 Bissell a clean bill of health as recently as September 2014. Due to the attention of ACCE, City inspectors visited the building again recently and found no serious problems but created a list of mainly cosmetic issues, such as “hallway closet doors off track.”

I visited the buildings on March 28, including the inside of some units, and I found them to be clean and well-kept.

ACCE members visited the home of Guadalupe Campos, the owner of 1300 and 1200 Bissell Ave, on Friday. Campos recently served low income tenants with a 20% rent increase. Campos lives on a hill overlooking the Bay in a very upscale neighborhood of Millbrae. Campos wasn't home but we left him a message and doorknocked his neighbors to ask them to call him and tell him to stop the rent increase. We took a picture in front of his Hummer. (Source: ACCE)

25 ACCE members and 15 of their kids turned out for the Richmond City Council Tuesday night calling on the City Council to pass Rent Control and a Just Cause Eviction ordinance. 7 new community leaders spoke about the 20% rent increase and bad conditions at their building, 1200 and 1300 Bissell Ave. One ACCE member asked the city council if they were going to side with the people or with the "abusers." The leaders gave really great testimonies especially about their health and safety concerns for their kids.(Source: ACCE)

Why rent control advocates have staked out Richmond as their front line is puzzling. Richmond (along with San Pablo) continues to have among the lowest residential rental rates in the Bay Area. San Francisco, Berkeley and Oakland, all of which adopted rent control and just cause ordinances decades ago, have not been successful in slowing spiking rental rates that soar far above those of Richmond. Even El Cerrito rents are, on average, 46% higher than Richmond.

1200 Bissell Avenue

Typical Living Room at 1300 Bissell

Private deck at 1300 Bissell

Bedroom at 1300 Bissell

Kitchen at 1300 Bissell

Fueling the fire is a recent report, Belonging and Community Health in Richmond by the Hass Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, and a sympathetic City Council. Instead of focusing on Bay Area cities that are truly in a housing crisis, such as San Francisco and even Oakland, Haas decided to go to Richmond, where some of the authors live and have close ties with ACCE and where a sympathetic and receptive City Council resides.

From Belonging and Community Health in Richmond:

This research report assesses the extent of gentrification in Richmond by analyzing changes in the demographics and housing market between the years 2000 and 2013. Gentrification trends in gentrification in Richmond are analyzed at the neighborhood level by adapting the methodology of previous analyses of Portland and the cities of San Francisco and Oakland. People and housing conditions are analyzed across three domains – Vulnerable population, Demographic Change, and Housing Market Conditions - to estimate the state of gentrification in a given city. The analysis is done at the level of the census Block Group, a set of boundaries created by the US Census that in Richmond have an average population of 1,428 residents.

The Haas press release described the report thusly:

BERKELEY CA/MARCH 09, 2015 – The new research, conducted by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, finds that gentrification is in its early and middle stages in some areas of Richmond, raising the susceptibility to displacement of vulnerable residents. The report, Belonging and Community Health in Richmond; An Analysis of Changing Demographics and Housing, also notes that the city’s African American population fell by 12,500 people between 2000 and 2013, while the Latino and Asian American populations increased and white populations have remained stable. Thirty-seven percent of total renters in Richmond earn less than $35,000 annually and spend more than 30% of their earnings on housing. The authors, Eli Moore, Samir Gambhir, and Phuong Tseng, conclude that “these facts raise concern that if regional trends of accelerating housing prices and persistent inequality hit Richmond, a substantial part of the city could be vulnerable”.

Rent control, gentrification and displacement are topics that generate great passion. For some, rent control it is a panacea for everything wrong with the housing market, and that approach is embraced by organizations including ACCE (Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment), formerly ACORN, and CCISCO (Contra Costa Interfaith Supporting Community Organization).

Without disputing any of the concerns about providing an adequate and stable supply of affordable housing, I subscribe to a different approach, that expanding the availability of affordable housing is a more effective and more sustainable solution than rent control. Future affordable housing in Richmond will come from several sources. A good place to start understanding Richmond’s housing strategy is the Housing Element of the General Plan. Virtually all affordable housing comes from one of the following:

- Richmond Housing Authority owned and operated units

- Section 8 vouchers

- HUD subsidized housing projects

- Low Income Housing tax Credit projects

- Inclusionary housing

Rent control is usually paired with a Just Cause ordinance that discourages investment in new rental housing in all but the hottest markets, which Richmond is not. No new significant market rate housing has been built in Richmond in over a decade, yet market rate housing is the only source for expanding affordable housing through the inclusionary zoning ordinance.

Greenway Apartments, a 90-Unit low-income senior housing project at Harbour Way and The Greenway

According to the General Plan Housing Element, Richmond has 36,940 households, 18,659 (51.7%) of which are owned and 16,162 (46.7%) of which are rented. In accordance with the Costa-Hawkins Act, any rental units that were constructed after February 1, 1995, and any units that are single family homes or condominiums are exempt from rent control by California Law. Any units that are HUD subsidized, Richmond Housing Authority owned, Section 8 or Low Income Tax Credit projects already are both rent controlled and subject to just cause. That does not leave that many units that would be subject to rent control if it were adopted.

Only eleven California cities continue to maintain rent control ordinances (governing residential rental housing) and have adopted regulatory schemes that restrict the viable reasons for which a tenant may be evicted. Aside from the eleven cities, other California communities have adopted rent control for mobile home parks. In California, there is an argument that the landmark property tax relief measure in the 1978 -Proposition 13 -gave rise to rent control. The argument goes that after the passage of Proposition 13 there would be a decline in property taxes. Landlords, it was presumed, would pass along those savings to renters in the form of reduced rents. When rent reductions did not universally materialize during an era of high inflation, consumer activists, looking for an opportunity to galvanize constituents, saw rent control as their issue. Their first attempt at enacting an ordinance failed. But the following year, Santa Monicans for Renters Rights (SMRR) was formed, and the group successfully enacted a tough ordinance that effectively froze rent hikes. The success of SMRR caught on and spread to other college towns –notably Berkeley, where rent control was also implemented. The early restrictive rent control measures were aimed at eliminating perceived windfall profits by landlords and, in turn, protecting the public welfare. (Rent Control Bad Economic and Failed Social Policy).

According to Rent Control Bad Economic and Failed Social Policy rent control results in the following negative effects:

- The trend in the rent control cities of Berkeley and Santa Monica showed negative growth in the number of rental units compared to their respective counties, which demonstrated positive growth. Moreover, this decline occurred at a time when California was experiencing a massive economic boom. These statistics support the assumption that rent control is a disincentive to maintain and construct residential rental properties

- Those people most able to help themselves (35-64) are benefiting from rent control, while the individuals the policy is meant to protect are benefiting the least. Rent control pushes certain age groups out of the rental housing market. Michael St. John, a Berkeley sociologist, determined that “rent control has actually accelerated gentrification in Berkeley and Santa Monica. Poor and working class people have been forced out of those communities faster than in surrounding municipalities.

- When fewer rental units are available, landlords are more selective when screening tenants. Using permissible selection criteria such as employment and income, a small number of units that become available tend to be awarded to people with higher incomes and predictable employment. cities practicing rent control continued to lose low-income households at a higher rate than the comparison counties. It provides support for the assumption that rent control does not maintain economic diversity. While the declines may only be modest in some cases, when the overall economic picture is taken into consideration (specifically the economic boom from the dot com explosion in the Bay Area), it is important to note that both cities lost low-income rental households at a greater rate than their respective counties

- Rent control splits the rental housing market into two segments – the regulated segment and the shadow market – those units that are not regulated. When prices in the regulated segment are kept artificially low, prices in the shadow market increase. And with the regulated segment of the market inaccessible to all but a chosen few, demand is increasingly filled by the shadow market at a higher price. Standard Supply and Demand Economic Theory predicts that any price controls, including rent control, will produce an excess of demand over supply, thereby promoting the emergence of so-called shadow markets. Shadow markets are alternative markets that serve as a safety net for excess demand above supply. In terms of rent control, “a ceiling on rents will reduce the quality and quantity of housing.”

- Given the disincentive to produce new housing in rent controlled jurisdictions and the inclination to hoard units held below market rates, some unfortunate consequences occur: longer commutes, crowded living conditions, scarcity of available housing, and even homelessness. Prospective tenants are pushed into the next community where the shadow market exists to take up the slack for the excess demand

For further reading, I recommend:

Finally, as a good will gesture , I have been successful in working with the Campos for a 25% rollback on their projected rent increases and a commitment for no more increases for a year. The rollback amounts to $600 for the next year. Rental housing landlords in Richmond are not our enemies. Many of them are hard-working individuals who have invested in our city and are simply looking for a fair return. We should not demonize them but instead work with them to expand our stock of new affordable housing and improve the quality of the existing stock, 74.4% of which is over 30 years old and 48.5% is over 50 years old. We cannot regulate ourselves out of an affordable housing crunch; we have to build our way out of it.

|

|