| |

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/01/22/uc-berkeley-proposes-global-educational-hub-its-own-backyard

Want to advertise? Click here

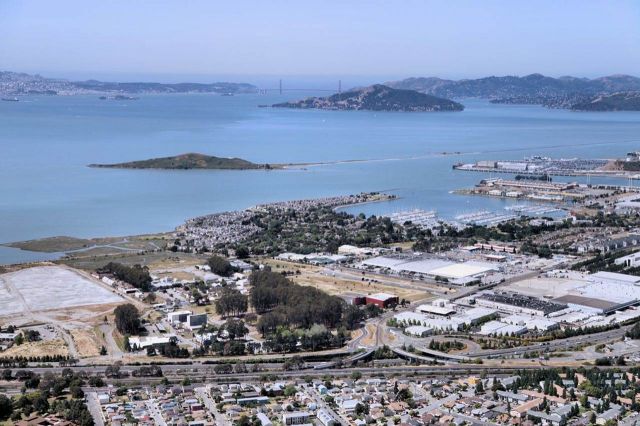

The site for the planned Berkeley Global Campus at Richmond Bay.

Courtesy of the University of California at Berkeley.

A Global Hub, Close to Home

January 22, 2015

Elizabeth Redden

While other U.S. universities have built branch campuses abroad, the University of California at Berkeley is betting it can create a global higher education hub in its own backyard.

Chancellor Nicholas Dirks has proposed that the Berkeley Global Campus at Richmond Bay will be “a new form of international hub” in which a group of leading foreign universities and technology companies will establish satellite locations on a 130-acre parcel of Berkeley-owned land located a mere 10 miles from the main campus. The plan is for foreign university partners to collaborate with Berkeley on research and the delivery of degree programs, and Dirks has laid out a broad educational vision for a “Global College," to be developed with the partner universities, that would aim to equip students “with the tools to tackle global challenges through a curriculum centered on global governance, ethics, and political economy; cultural and international relations.”

Berkeley officials say they are in concrete discussions with potential foreign university partners interested in participating. Dirks declined to share the names of the universities that Berkeley is negotiating with, though he did drop hints based on his travel schedule: “I’ve traveled recently to universities in Singapore and China and Japan and I’m on my way tomorrow to Cambridge, England,” he said last Friday. “I’m just doing a lot of traveling.” This week he is in Davos talking up the concept at the World Economic Forum.

Unlike existing global educational hubs sponsored by governments, which typically subsidize campus construction and, to varying degrees, the operating costs of the foreign universities that agree to come there, Berkeley is counting on foreign university partners to bring the capital needed to build up the campus. The bayside land was originally going to be the site of a second joint campus with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory until construction plans stalled due to federal budget cuts and the lab's failure to secure a crucial $1.5 billion contract.

In attracting foreign university and corporate investments to develop the site, Berkeley does have the advantage of its brand name and its location in Northern California. As Nils Gilman, the associate chancellor and chancellor’s chief of staff, said, “Part of the appeal of the Berkeley Global Campus concept to partners is that this is a chance to not just partner more deeply with Berkeley and with a handful of other elite global universities but also to get a foothold in Silicon Valley.”

“I was in New York before I came here and I watched the whole process where two strips of abandoned land just off the shore of Manhattan were put up for bid by [then-Mayor] Michael Bloomberg and saw the interest that it generated both across the U.S. and indeed across the world – even Stanford was intrigued,” said Dirks, who was executive vice president and dean of arts and sciences at Columbia University before coming to Berkeley.

“My sense of this in part was informed by watching this process. Of course, that was a city and there was some money that was involved in attracting interest, though the truth of the matter is the money that was used by Bloomberg was minimal. It was mostly about real estate. And it was the old line that every realtor uses: location, location, location.” (New York City offered land and $100 million in capital for the creation of a new tech campus on Roosevelt Island, the bid for which was eventually awarded to Cornell University and Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.)

An Alternative Model

The proposed Berkeley Global Campus model stands out as an approach to internationalization in that Berkeley seeks to bring foreign universities to California rather than build its own campus overseas.

Dirks said that Berkeley, like every other major university, has been approached about building an international branch campus. “We weren’t inclined to move forward with the branch campus model,” he said, citing, among other concerns, the issue of academic freedom. As other Western universities have developed branch campuses in places like Abu Dhabi, China and Singapore, they've faced persistent questions about whether they can uphold their commitments to academic freedom -- a predicament that's arguably complicated by the fact that the branch campuses tend to be financially beholden to their (in many cases authoritarian) government sponsors.

"A global campus situated in this country also offers significant advantages and protections when it comes to issues that can be problematic for branch campuses located overseas," Dirks told Berkeley’s Academic Senate in an address in the fall. “At home we are on much more solid ground when it comes to protecting and supporting academic freedom, transparency, different forms of advocacy and political engagement, and protection of intellectual property. Situated along the Bay, the [Berkeley Global] campus will be a true safe harbor (a term that universities with branch campuses in mainland Asia and the Middle East use with considerable anxiety).”

Dirks also noted that the development of a far-flung branch campus doesn’t always bring tangible benefits to the home institution.

“I primarily was interested in making sure that anything we did would make a direct contribution not just to our home campus but also to the State of California,” Dirks said in an interview. “This is in part trying to think through what model would be most consistent in being not just a leading university but a leading public university.”

Jason E. Lane, the vice provost for academic affairs and co-director of the Cross-Border Education Research Team at the State University of New York at Albany, said he would describe Berkeley’s plan as less of a branch campus “and more as the next iteration of partnerships.”

“In my mind, from a Berkeley perspective, there’s very little about this that is an international branch campus experience, but certainly it sounds like they are taking the idea of joint research and academic programs to another level. Rather than having a partner that’s based in a foreign country and working in a more virtual space, they are looking to locate their partner near them so they create a physical entity that is a jointly owned operation.”

The U.S. has traditionally been an exporter, rather than an importer, of international branch campuses. Researchers at SUNY Albany have identified seven foreign universities that have or are developing branch campuses in the U.S., but Lane said Berkeley’s is the first attempt to build a global educational hub here.

Devil in the Details?

Dirks has maintained that the university will not divert substantial central campus resources to fund the new Richmond Bay campus. Gilman, the chancellor’s chief of staff, said he anticipates that the main sources of funds for the proposed campus will be money brought to bear by foreign university and corporate partners as well as gifts from Berkeley alumni and other donors. Gilman added that while Berkeley officials do not expect a 1960s-style appropriation from the state legislature, they are hopeful there will be government support in the form of tax breaks or other incentives.

Many of the details are still to be determined, but university officials say that as far as construction of the campus goes, Berkeley is considering various financing options, including the awarding of long-term ground leases in which the university would lease rights to land on which the lessee would construct a new building. The lessee/partner would own the building (but not the underlying land) for a period of, say, 50 years, after which point ownership of the building would revert to the owner of the land, which will continue to be the University of California. The campus at Richmond Bay is already home to a number of buildings and scientific facilities, including a wave tank and an earthquake shake table.

In regards to academics, Gilman said that Berkeley is initially looking work to with a group of fewer than half a dozen foreign universities that will be “anchor partners.”

"Right now the guiding vision is that probably the way we’ll start with each of the universities we’re in dialogue with is with a topically focused institute that will be housed at the Berkeley Global Campus but will then provide a platform for building a bigger and deeper relationship over time,” Gilman said. “For example, we have one partner in Asia who is very interested in climate change; we might do a joint climate change research institute with them.”

In most cases Gilman said that the potential partner universities are interested in developing master’s programs in conjunction with their research programs, though a whole variety of types of degree structures – in which the foreign university alone delivers the degree, in which the foreign university and Berkeley each issue dual degrees, and in which the two institutions grant a single, joint degree with both university names – remain on the table. ("This is not going to be a one-size-fits-all kind of arrangement," Gilman said.) The expectation is the campus will begin by offering graduate degrees, though Dirks has also floated plans in which Berkeley undergraduates could spend a semester abroad at a partner university followed by a research-intensive semester at that same university's California outpost.

“We will be making announcements within the next year about partner universities, about the initial programs, both educational and research ones, and about some initial gifts that will help us begin this in a serious way,” said Dirks.

“I think in three years we’ll have our first new building and in five years I think we’ll probably have three to four buildings, multiple master’s programs and new kinds of opportunities for undergraduates doing study abroad,” as well as internships pegged to new corporate partnerships, Dirks said.

Panos Papadopoulos, the chair of Berkeley’s Academic Senate and a professor of mechanical engineering, emphasized that many of the specifics are still being figured out. “I’m involved in a lot of the conversations and in that sense the Senate is being kept up to date. There’s a flurry of activity, there’s a lot of discussions with a lot of partners, but we’re still in the formative stages. We’ll see. I look forward to seeing how it materializes.”

Papadopoulos said the feedback he’s heard from faculty so far has largely been positive, though there have been concerns about the potential diversion of resources away from the core campus (which the chancellor has said will not happen) and questions about feasibility. If the campus is developed as planned Papadopoulos believes it will be “absolutely transformational," but he also knows Berkeley has a long road ahead.

“From where I stand -- and this is not a Senate position, it’s my personal view -- I think this is a project that is a high value project but it is a challenging project to bring to fruition for the very simple reason that it will require a number of different entities, both academic entities and non-academic entities, to align with the project in a relatively short period of time. So universities from across the globe and private partners in a short period of time, in three years' time, will have to see the value of being involved in it and invest resources and people’s time to see it happen.”

|

|