| |

We have reached the traffic tipping point in the Bay Area. We were flirting with it in 2001, but the dot-com deflation, 9-11 and the Great Recession gave us over decade of relief. That is over.

The signs are everywhere. Rush hour trips that used to take 45 minutes are now 1½ hours, or more. And a collision, rain or construction can slow traffic from a crawl to a dead stop for hours. For the first time ever, the Richmond-San Rafael bridge has reached rush hour capacity.

It takes pretty much at least an hour, and for many people far more, to commute via car from anywhere to anywhere, and it takes a heavy toll on those who choose to live one place and work in another. Two hours a day on the road commuting adds up to 500 hours a year. That’s the equivalent of over 62 full 8-hour work days. If you were getting paid for it, even at minimum wage, it would cost the equivalent of $5,000 a year. If you make even the median Bay Area income, it will be closer to $10,000. Assuming an average commute of 25 miles and the IRS mileage cost of $0.55/mile, and add another $7,000. If you add parking cost, it would be even more.

Lots of people still think we can build our way out of this by adding lanes to existing freeways or by even adding more freeways. It won’t work, and the relief it provides is only temporary at best. It will just get worse.

We have designed our urban region based on the concept that driving time and driving cost are negligent quantities in the daily activity equation. If you don’t want to live where you work or work where you live, no problem. You just drive back and forth. Neglecting to calculate the cost of commuting, in both dollars and time has been the primary driver of sprawl. The rise of shopping malls and big box stores was built on the premise that cost of goods was all that mattered. The cost of getting there and back was ignored, but now it is becoming significant.

In the 1950s, America’s largest corporations destroyed perfectly fine public transportation systems in order to sell more cars, buses, gasoline and tires. Now, they have sold so many that they are all gridlocked.

Even the new public transportation systems that have come to replace the old, such as Caltrain, are at capacity, but we are not investing in some modes fast enough, such as ferries, and we are not expanding BART, light rail and our bus systems fast enough.

There are only two ways out of this: (1) another recession or (2) making regional and city planning choices, as well as personal choices, that veer away from the current trend. I don’t think anyone would vote for another recession. The three most important things we can do are:

- Invest in public transportation infrastructure, and plan our cities and our region in a way that takes advantage of it, such as transit-oriented development, walkable communities and complete communities that provide not just housing but also schools, routine shopping, amenities and public services. This trend has come to be known as “smart growth” or “new urbanism.”

- Start to decentralize the relationship between where people live and where they work, shop, play and go to school. The current model is unsustainable. People should have easy access to these needs either by walking or by public transportation. The car-oriented suburban model is a disaster.

- Institute economic incentives for people to live closer to where they work. This is not just a time and expense issue; commuting and driving for other reasons is the largest contribution to greenhouse gases and global warming in the United States. This would be a good use of cap and trade revenue.

I admit that I can gloat a little. I live less than a half mile from where I work. My commute time is measured in minutes. Within walking distance of both home and work, there is a regional park, a natatorium, two grocery stores, a pharmacy, a community playhouse, a library, a fire station, a movie theatre, an elementary school, bus stops and over a dozen bars and restaurants. If I did not have projects around the Bay Area that I have to visit periodically, I could theoretically exist just fine without a car.

Maybe we are going this direction. The Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority have adopted the Bay Area Plan that was designed to implement or encourage policies in AB 32 and SB 375, by recognizing the link between transportation and housing and trying to reduce vehicle miles traveled.

On the other hand, I am a member of the Contra Costa Transportation Commission (CCTA), and despite a lot of lip service to sustainability in the Contra Costa Countywide Transportation Plan 2009, the transportation bureaucracy, the transportation lobby and most of the elected officials who sit on CCTA continue to be obsessed with paving and highways. If you go to the CCTA website (http://www.ccta.net/) for a list of projects, there are ten freeway projects to add lanes and expand interchanges and only one public transportation project, e-BART.

CCTA Projects

Again, we cannot pave our way out of this traffic mess. We have to devote our resources another direction.

As economy strengthens, commute worsens around Marin and the Bay Area

Bay Area News Group

Posted: 11/17/2013 01:00:00 PM PST

Brakelights come on as Highway 101 southbound traffic grinds to a halt during commute hours on Thursday morning, Nov. 14, 2013, in Novato, Calif. Economic recovery may be adding cars to the roads. (Frankie Frost/Marin Independent Journal) Frankie Frost

Click photo to enlarge

Highway 101 northbound traffic, left, flows smoothly as southbound traffic grinds to a halt...

Bay Area commuters are getting a sinking feeling as we see firsthand what economic recovery looks like — miles of brake lights on commutes so congested we're wasting hours a week inching to work and back.

It almost makes you miss the recession.

Commuters say trips that took 30 minutes a year ago now may take 60 or more. It's on Highway 101 through Marin, happening on Highway 85 in the South Bay, Highway 101 along the Peninsula, Interstate 880 through the East Bay and Interstate 680 from the Sunol Grade to the Benicia Bridge.

Forget talk about Twitter stock. When people gather around the office water cooler, it's often to gripe about traffic, traffic, traffic.

"People driving more than ever are seeing the value of carpool lanes," said Mike Ghilotti, president of San Rafael's Ghilotti Bros. Inc., who has his crews working on the lanes in Novato this year. "The economy is turning around and the commute is getting harder in the morning and the evening."

It's not just Marin, but all over the Bay Area. San Jose had the 13th worst congestion in the nation in 2010, but now ranks fifth, according to Inrix, which monitors traffic nationwide. Delays are also growing through San Francisco and Oakland, which are counted together and are considered the country's third-most congested city, a spot it has held for years.

"It's gotten noticeably worse, even in the last two weeks," said KQED traffic reporter Joe McConnell. "Every morning has been nightmarish.

"Something may have tipped, but it could be like trying to connect any particular stormy day to climate change or just bad weather."

Mostly, experts say, the congestion is a testament to the growth in jobs in Silicon Valley, San Francisco and the North and East Bays as the economy recovers from the Great Recession. And that has exacerbated problems that were already worse here than elsewhere.

Where drivers nationwide spend about 38 hours stuck in traffic a year, drivers in California's most urban areas waste 62 hours a year, says the Texas Transportation Institute.

"You see it out there," said Marin Supervisor Judy Arnold, who treks around the county from meeting to meeting. "It definitely points to a need for different options such as the SMART train. Traffic will not be getting any better."

Road construction is underway seemingly everywhere. Schools are back in session. Gas prices have fallen 28 cents a gallon over the past year. And more traffic on the road means likely more crashes that make things even worse.

While ridership on Golden Gate Transit buses and ferries, BART, Caltrain and rail continues to grow, carpool use is on the rise. And there are simply too many driving solo to work.

Traffic is stopped on 101 northbound during commute hours on Thursday morning, Nov. 14, 2013, in Novato, Calif. The economic recovery may be contributing to traffic problems. (Frankie Frost/Marin Independent Journal) Frankie Frost

"You see all the solo drivers in the carpool lanes too, it's frustrating," Arnold said.

That said, the percentage of solo drivers in Marin who commute to work is among the lowest in the Bay Area, only behind transit-heavy San Francisco, according to U.S. Census data.

The data also suggest Marin has the highest percentage of workers in the Bay Area who walk or bike to work, or simply work from home.

The data show that 65.2 percent of Marin workers drive alone, second only to San Francisco, which sees 37.6 percent of its workforce go solo in a car, according to figures from the census' 2011 American Community Survey, which is based on questionnaires given to workers age 16 and older. Alameda County is a close third behind Marin with 65.4 percent of its workers driving solo. Solano County has the highest percentage at 76.7 percent, almost even with Santa Clara County at 76.6 percent.

But 65 percent of people driving solo is still substantial and the traffic mounts. In Marin, transportation officials are looking at ways to ease the commute. Metering lights at key onramps and changing carpool hours have been discussed.

The Transportation Authority of Marin will spend $190,000 to look at ways to ease gridlock around the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge, including opening a third lane eastbound on the span during the evening commute. The slowdown around the span causes traffic to back up onto northbound Highway 101 in Marin.

Other parts of the Bay Area are facing even worse conditions.

Rod Diridon of the Mineta Transportation Institute says Silicon Valley will soon bump against "terminal gridlock" like the kind that occurred in Beijing six years ago when commuters were trapped in their cars for days.

"The capital of China was nearly paralyzed for almost seven days while that massive traffic jam was cleared," Diridon said. "That crisis doesn't happen gradually. There is no quick fix."

IJ reporter Mark Prado contributed to this report.

Latest News

Improving Bay Area Economy Pushing Caltrain Ridership To Limit

November 29, 2013 6:07 PM

Passengers exit a Caltrain at the San Francisco station. (CBS)

SAN MATEO (KCBS) — Thanks to the improving employment picture in the Bay Area, many mass transit systems are seeing increased ridership, pushing Caltrain to its limits. are seeing increased ridership, pushing Caltrain to its limits.

“We’re up to about 54,000 [riders], so these are all-time levels,” said Caltrain board member Ken Yeager. “I’ve been on the Caltrain board for 13 years and remember when it was sort of in this 30,000 level, but the fact that we’re up to 52,000, 54,000 really should show you the incredible increase in capacity and ridership that we’re having.”

Yeager said that the increase is a mixed blessing and is glad people are riding, but the concern, he said, is slowly mounting that at some point the trains might reach capacity.

He noted that the freeways are totally clogged and that commuters are looking for alternatives, but that the system can only handle so many people and trains. can only handle so many people and trains.

Yeager asked for a report at the next board meeting to see exactly what the capacity levels are. He added that another major issue is to complete the Environmental Impact Report so that electrification of Caltrain’s system can begin in 2019. Impact Report so that electrification of Caltrain’s system can begin in 2019.

(Copyright 2013 by CBS San Francisco. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.)

Improving Economy Creating Gridlock On Bay Area Freeways

November 12, 2013 7:04 PM

View Comments

Commuter traffic backs up at the toll plaza to the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

SAN FRANCISCO (KPIX 5) – The improving economy is likely to blame for increased commute times around the Bay Area. More people have jobs than a few years ago, and most still like to drive their own cars.

The Metropolitan Transpiration Commission says we usually see more traffic during the commute hours in the fall, but Bay Area Bridges are 2-3 percent busier than they were last year.

“Even if you don’t use a bridge, people are backing up on city streets as they try to find alternates around and it’s just a nightmare,” said KCBS traffic Anchor Sheryl Raines, who has been monitoring road conditions for 25 years. “I think it’s the worst, and I think its even getting worse. You know, every night there’s some backup.”

One reason why it’s getting worse is the economy is getting better. The Bay Area Council says we are back at our pre-recession unemployment rate.

“Since 2010 we’ve added 300,000 jobs here in the Bay Area,” said Rufus Jeffris of the Bay Area Council. “You don’t do that without having some impact on traffic.”

His group forecasts the region will add another 200,000 to 300,000 jobs in the next two years.

An exclusive KPIX5/SurveyUSA found 71 percent of people commute to work and an additional 23 percent both commute and work from home. Of those, 80 percent drive their own vehicle, and the majority – 52 percent – say the like the flexibility and freedom. Click here for the full survey results (.pdf).

|

Traffic Congestion - It's NOT the Economy, Stupid

by Casey Mills‚ Sep. 19‚ 2005

Last Thursday, the San Francisco Chronicle published an article connecting worsening commute traffic in the Bay Area with improvement in the local economy. Yet the article glaringly omits a variety of recent political decisions discouraging people from riding public transit, including hikes in BART, MUNI and AC Transit fares and service cuts throughout the region. And when offering solutions to the congestion, five out of six involve making car travel quicker and easier. Why is the most progressive area in America looking to solve traffic congestion by dumping more money into highways instead of with smart urban planning and more funding for public transit?

The September 15 Chronicle article, "Traffic gridlock breaks trend - it's worse," documents a report issued by CalTrans and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission. The report shows a recent, sharp reversal in what had been decreasing traffic congestion. But rather than questioning whether the switch could be tied to more expensive, less dependable buses and trains, the Chronicle takes at face value official claims that it's because of a burgeoning economy.

Shockingly, a district director of CalTrans calls the trend "good news for the Bay Area" because of its claimed connection with improving commerce. Perhaps even more revealing about public agencies' attitudes towards solving traffic congestion problems, however, involves the Chronicle's list of proposed solutions to them.

With the exception of keeping a freeway median strip open for possibly someday extending BART farther east, every solution involved wider lanes, new interchanges, and other improvements to local highways to speed up car transit.

Ensuring transportation is cheaper, more reliable, more frequent, and made available to more areas, however, remained off the table. In a region whose voting pattern makes it one of the most environmentalist regions in the country, this makes no sense.

Virtually no one in the Bay Area discounts the theory of global warming, and a large majority here considers it a national priority to reverse its dangerous effects. We're a headquarters for environmental organizations like the Sierra Club and Global Exchange, a bastion for radical thinking around progressive solutions to our environmental ills, and candidates vying for state-wide office are often forced to adopt at least some green positions to cater to the region's voting bloc.

All of this, it would seem, would create an atmosphere where government took every step possible to get people out of their cars and into public transit. Yet our transportation policies often seems like they'd be more at home somewhere in Texas.

There's simply no denying that supplying more funding to public transportation would lessen traffic congestion. But another, more involved solution is just as important - smart, transit-oriented urban planning. As much as the Bay Area trumpets a car-free future and the importance of cleaner air, its urban sprawl rivals that of far more conservative regions.

This trend could be reversed - and traffic congestion decreased- by building most new development along transit corridors, and creating more dense developments that combine housing and commercial use. But it takes a strong political will by government officials that, judging by the Chronicle article, does not exist.

There's a variety of possible reasons why the Bay Area's transit policy does not mirror the progressive politics of its residents, including it being a low priority for many politicians and activists; the deeply entrenched ruts of car culture pervading decision-making about such issues; and planning decisions made in years past that remain difficult to reverse.

But it certainly doesn't help the situation when Northern California's largest daily documents worsening traffic congestion while refusing to even mention some of its likely root causes. Nor does it help when public officials celebrate the congestion as indicative of a better economy.

The Bay Area needs to take a long look at ending traffic congestion, but not just so people don't have to sit around in their cars too much. It needs to solve the problem to bring cleaner air to our homes, to decrease our dangerous dependence on foreign oil, and to preserve the open spaces and natural landscapes that inspire pride in so many residents here.

If given a choice between these benefits and a marginally better economy, it's hard for me to imagine many of us 'crazy Bay Area liberals' choosing the former.

Copyright © 2005-2011 Beyond Chron.org. All rights reserved.

RSS News Feed |

|

As economy rises, so does Bay Area transit congestion

By Mike Rosenberg

mrosenberg@mercurynews.com

Posted: 09/04/2012 09:52:34 AM PDT

Updated: 09/04/2012 10:10:37 AM PDT

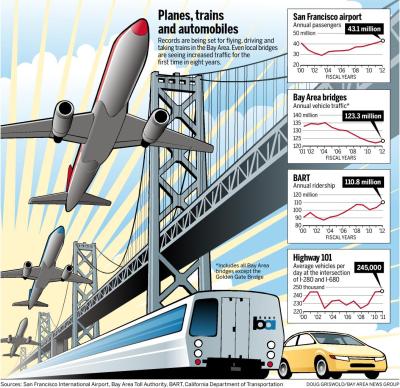

From Highway 101 to BART to SFO, traffic records are falling across the Bay Area.

More drivers are clogging Silicon Valley's busiest stretch of freeway now than they did during the dot-com bubble. Bay Area trains are more packed than when record gas prices peaked in summer 2008. And the region's biggest airport is busier than its pre-9/11 high.

The reason? The workforce from San Francisco to San Jose is the largest it has been in more than a decade, while East Bay worker totals are at their highest since 2008. And while airports, trains and freeways are busier these days across the country, the trend in the Bay Area is even more pronounced.

"I guess you could say it's kind of exciting to see traffic again," said Jim Wunderman, CEO of the Bay Area Council business group. "If there's frustration -- gripping the steering wheel a little bit harder while sitting in bumper-to-bumper traffic -- at least more people are employed."

More traffic also means more train fares and gas tax revenues to keep transportation systems moving. But we're also leaning more heavily on an aging infrastructure network, and we're beginning to remember that an improving economy means more time at the wheel, standing on packed trains and waiting for delayed flights to take off.

"After the last few years, I think most people are willing to bear those inconveniences," said John Goodwin, spokesman for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

Driving

Santa Clara County's busiest bottleneck -- where Highway 101 splits Interstates 280 and 680 -- featured more vehicles in 2011 than ever during an average day, according to Caltrans data. The most heavily traveled stretch on the Peninsula, Highway 101 in San Mateo, set a record last year for rush hour vehicle counts after an extra traffic lane was added to meet the demand.

Tom De Vries sure notices.

"It is more congested during rush hour," said the Redwood City resident who often travels with his wife so they can breeze by traffic in the carpool lane. "We try to time our shopping trips so it's not during rush hour."

And all those extra cars are tying up Bay Area bridges. During the fiscal year that ended in June, the region's toll bridge traffic went up for the first time in eight years, with an extra 1.2 million vehicles -- a 1 percent increase -- compared with the prior year. The San Mateo and Richmond bridges are at their busiest in four years.

"It's a lot heavier," said Scott O'Donnell, who drives from Hayward to his financial services job in Alameda. "You have to be on the road before 7" in the morning.

Around the nation, miles driven by U.S. motorists increased 1.2 percent through the first five months of this year compared with last year, with an especially-pronounced bump in California.

But traffic in the East Bay, San Francisco and on the bridges still lags behind last decade's peak, and a few spots -- like the busiest freeways in Alameda and Contra Costa counties -- are nowhere close to record congestion, as employment levels there have yet to return to previous highs.

Riding

The transportation trend is perhaps best illustrated by BART, which this month announced a ridership record after adding nearly 10 million annual passengers in two years. Now BART is launching extra trains on the Millbrae-to-Richmond line and has balanced its budget a few years after cutting service.

"It used to be you'd get on BART at 7 at night and there'd be like one person per double-seat at most. Now, at 7 at night the stations are still crowded," said Cupertino resident Dave Morris, who has been riding BART off-and-on for 30 years.

Caltrain also just posted an all-time-high rider count after surging 17 percent in two years. San Francisco Muni and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority each grew nearly 3 percent in the fiscal year that ended in June.

Gas prices, which are still about 50 cents a gallon below the all-time high, and the extra freeway traffic are helping transit agencies pick up new passengers.

"To be very honest with you, gas prices got everyone's attention," BART General Manager Grace Crunican said.

But Crunican said one thing "is going to come back to bite us." The extra riders increase wear and tear on infrastructure and usually help fund operations, not things like replacement vehicles. BART needs $7.5 billion to fix "the guts" of its system while the total debt for Bay Area roads and transit repairs is expected to rise above $50 billion later this year, Goodwin said.

Flying

More than 43 million passengers traveled through San Francisco International Airport in the fiscal year that ended in June, breaking a record set in 2001 before air traffic plummeted after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. SFO is the fastest growing large air hub in the nation, with traffic soaring 8 percent in the past year.

Most of SFO's newfound travelers are simply dumping Oakland and San Jose airports, which now combine to offer only 30 percent of all Bay Area flights, down from nearly half at one point last decade. As struggling airlines look to save money, they have shifted their flights to the biggest hubs.

Still, Oakland has rebounded to its busiest point in three years. The smallest of the three airports, though -- San Jose -- continues to shrink.

SFO is already one of the most delayed airports in the nation, earned mostly because of foggy conditions, but it's getting worse. SFO's delays have risen from a low-point average delay of 40 minutes a decade ago, when traffic bottomed out, to 65 minutes now. The airport and the FAA are working on a new air traffic control system to relieve congestion while regional officials are weighing price incentives to persuade airlines to shift traffic to Oakland and San Jose.

Contact Mike Rosenberg at 408-920-5705. Follow him at Twitter.com/rosenberg17.

Defining a rider

You may be surprised to know that every time you take a round trip on a Bay Area bus or train, you're counted as two riders -- one for each direction.

The "ridership" totals posted by transit agencies here and around the nation actually reflect one-way trips, a fact that's rarely spelled out to the public.

Consider BART, which boasted in a news release this month that it had broken a record by tallying 366,565 average daily riders during the fiscal year that ended in June. But that figure represents one-way trips, and the actual number of daily people riding is about 200,000 -- with the average person being counted 1.8 times, because most people take round trips.

The totals continue to mount when you transfer transit lines, as well. Ride AC Transit and BART to work, then take the same way back home, and you'll be counted as four riders -- two for each agency.

In all, when factoring in round trips and transfers, the average person riding Bay Area transit is counted about 2.2 times per day, according to government data provided from the region's Clipper card payment system.

|

|