| |

Richmond: Chevron to try again for refinery modernization project

By Robert Rogers

Contra Costa Times

Posted: 10/28/2013 06:07:01 AM PDT

Updated: 10/28/2013 06:07:43 AM PDT

The Chevron refinery and storage tanks are seen from Crescent Avenue in Point Richmond, Calif., on Thursday, Aug. 9, 2012. (Jane Tyska/Bay Area News Group Archives)

Related Stories

· Oct 26:

· Document: Richmond Chevron refinery modernization application

RICHMOND -- Jeff Hartwig strides toward the 95-foot hydrogen furnace, pebbles crunching underfoot. Humming fans give the massive steel structure the illusion of activity.

But the structure, designed to produce hydrogen used for hydrocracking, a process that turns crude oil into simpler molecules more readily convertible into transportation fuels, lies idle. Hartwig, clothed in a blue coveralls, safety goggles and a white helmet with a Chevron logo on the front, peers up toward the sun as he climbs the steel staircase.

"This is ... the biggest project I've ever been a part of," said Hartwig, a veteran chemical engineer first hired by Chevron in 1980. "It's hard to overstate how important this project is to our operations."

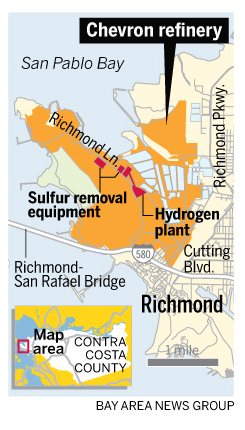

Hartwig is the man tapped by the global energy giant to achieve what has been an elusive goal more than a decade in the making, a $1 billion-plus modernization of its century-old, 2,900-acre Richmond refinery. For now, fans bathe the facilities in dry air to ward off corrosion while the company awaits permission to resume construction that was halted by a judge four years ago.

Chevron officials, and numerous documents, describe the modernization as an important upgrade in an increasingly competitive global petrofuels market. The conditional use permit application submitted to the city in 2011 says the plan is a scaled-back version of a much more ambitious project squelched in state court in 2009.

The road to approval won't be easy. Longtime Chevron critics are already raising questions about the processing of high-sulfur crude and the possibility of increased greenhouse gas emissions.

Mayor Gayle McLaughlin, the only Green Party mayor of a city of more than 100,000 people, has signaled that the city won't just rubber stamp permits. "Ultimately, we'll have opportunities to put conditions on the permit," McLaughlin said. "It's important that this project not only comply to (California Environmental Quality Act) rules but that it actually bring forward a truly healthier refinery -- one that reduces current levels of (greenhouse gas) emissions and all other pollutants, while putting safety first above the refinery's efforts to increase production and profits."

The new modernization project would allow the refinery to process crude oil blends and gas oils with higher sulfur content, which it says is critical to producing competitive-priced transportation fuels and lubricating oils. In addition, it would replace the refinery's existing hydrogen-production facilities, built in the 1960s, with a modern plant that is more energy-efficient and yields higher-purity hydrogen, and has the capacity to produce more of it.

In today's refining environment, marked by tight margins and mounting regulatory challenges, the ability to process high-sulfur crude is increasingly important.

"It's not the same project that it was 10 years ago," Hartwig said. "The first time around, we thought that demand for gasoline would keep going up, but now with higher fuel efficiencies, the economics is just not there. This project is smaller, but it's smarter."

In the old days, Hartwig said, refineries converted about half a barrel of crude into high-quality fuels, leaving the other half for asphalt and heavy fuel oil for power plants and factories.

Through hydrocracking and hydrotreating, refineries can convert about 90 percent of the barrel into a more valuable, cleaner fuel that meets higher standards than were in place decades ago.

The stumbling block, if there is one, seems to be whether the modernization will result in increased emissions, a possibility most elected officials in the area seem dead-set against. The city has retained its own consultant to craft local greenhouse gas-mitigation measures -- including energy efficiency, urban greening and transportation projects -- and several council members have already signaled they want to see emission reductions at the refinery, not just emission-neutral changes.

While Hartwig said the modernization would result in a refinery that produces "essentially flat or lower greenhouse gas emissions," he cautions that the environmental impact report will require the refinery to estimate emissions in the event of full-capacity production. That estimate will show the potential of an increase in emissions.

"In a perfect world, we achieve less emissions, better efficiency and safety and good jobs in this modernization," said county Supervisor John Gioia, who represents Richmond. "But for me, the most important issue is that there not be any increases in emissions from the project. I'm not going to give an inch on that."

In 2009, a judge sided with environmental groups that sued to halt the modernization, ruling that the company's environmental report fell short in explaining the changes in crude that would be processed and outlining plans to mitigate greenhouse gases.

There are concerns about what could potentially be an unprecedented spike in the amount of sulfur circulating through the plant's piping systems. Since the 1990s, the amount of sulfur in the oil Chevron processes increased from roughly 1 percent to 1.6 percent. The modernization would allow the refinery to begin handling sulfur as high as 3 percent.

When a crude unit ignited into flames because of pipe corrosion on Aug. 6, 2012, sending 15,000 people to area hospitals, subsequent investigations found that accelerated corrosion -- resulting in part from sulfur and low silicon content in piping metals -- played a role. Chevron officials are adamant that the modernization would include new piping materials more resistant to corrosion.

Greg Karras, a senior scientist at Communities for a Better Environment, one of the groups that sued Chevron to halt its project in 2009, said the sulfur content alone is "extremely troubling."

"It seems clear that the refinery can't handle the sulfur content level it has now," Karras said. "The 3 percent level is very high within the industry. Until we see that EIR, we have no idea how they plan to address it, because they haven't divulged it yet."

Moving forward, Hartwig said concerns about safety and emissions would be scrutinized and addressed.

The draft environmental report is expected to be released in January, followed by two months of review and public comment.

The council could review the final environmental report as early as June, and construction could begin in 2015.

|

|