| |

Housing plan sparks arguments on rent control, just cause evictions

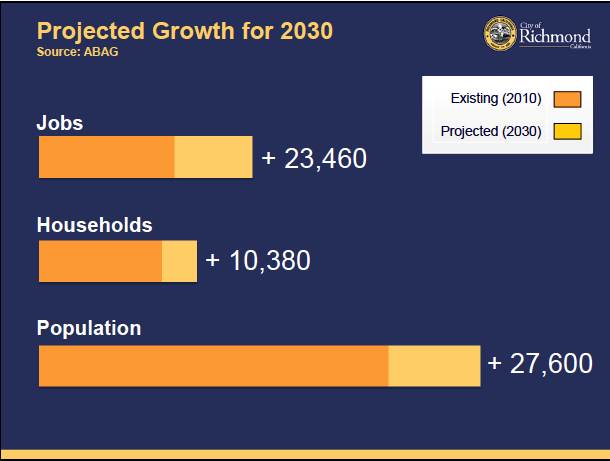

Graph courtesy of the Richmond Planning Department

By Wendi JonassenPosted January 23, 2013 3:52 pm

After several hours of confusion and bickering, last week the Richmond City Council approved a housing element—a part of the general plan that will address land use and housing development throughout the city—just in time to meet a deadline to be eligible for a state-issued $44 million grant.

But although the entire housing element contains more than fifty sub-sections, there are still four sections of the plan the council left undecided, which could affect rent control, eviction laws and low-income housing requirements in Richmond. Those four subsections cover enforcing stricter just cause eviction protections, establishing rent stabilization and a rent control board, creating a community land trust, and restricting the circumstances in which a developer can pay “in-lieu” fees instead of building low-income housing.

All of these subsections are either controversial or are only in beginning stages of research. At last Tuesday’s meeting, after two and half hours of discussion and over 20 speakers from the community, the council did not actually vote to implement any of these items. Instead, they spent several hours arguing before voting to allow the Planning Division to spend the rest of the year doing research on them.

“The only thing we will have to do now and between the end of the year is come back to the city council with studies,” said Hector Rojas, a senior planner in the Richmond Planning Division.

As rent soars throughout the Bay Area, the population in Richmond is expected to grow by 10,380 households between 2010 and 2030 according to the Planning Department. With the Lawrence Berkeley Nation Lab coming to Richmond, many expect that to add to the population boom, in addition to adding jobs. That’s raised concerns about gentrification—that low-income residents will be pushed out of Richmond.

Today, Richmond is a Bay Area leader in low-income housing. Neighboring cities average meeting 32 percent of their affordable housing needs while Richmond sails above with 300 percent of its affordable housing options met, according to a 2002 report done by the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California.

However, homelessness continues to be one of Richmond’s biggest issues. Richmond has the largest homeless population in Contra Costa County, with 2,266 homeless people or families according to the Planning Department.

No one, not even experts in the Planning Department, yet knows how the four controversial elements could affect Richmond as the city braces for the population boom. The planning department will spend the year talking to other cities about their policies on similar matters, looking over statistics, and talking to elected officials to try to get a better idea of what Richmond needs to do to attract developers and money, while still providing for the low-income population. For example, when Councilmember Nat Bates asked for solid data on eviction problems, Rojas said that that was an area that needs more study.

“We do need a year’s time to look over this and that is not including outreach to the community, talking to stakeholders, and making our own recommendations on each and every one of these programs,” Rojas said. “There are a lot of questions.”

The answers to those questions will affect housing development, land-use, rent, tenants’ rights and low-income housing in Richmond for many years.

Rent Control

At the last council meeting, the rent control element of the plan easily took over much of the debate between councilmembers, residents and property owners who were ready to cite statistics and voice concerns.

If implemented, this clause would enact rent controls, which are limits on how much and how often landlords can raise the rent. In order to do this, Richmond would need to establish a rent control board that would oversee new developments and manage landlords. The board would only allow landlords to raise rent by a certain percentage every few years to keep rent affordable, but that percentage and the time period for how often landlords could raise rents is not specified in the clause. The Planning Board will spend the year researching to work out these details, Rojas said, unless, of course, they decide rent control won’t help Richmond.

Renting is a key issue since over half of Richmond residents rent instead of owning property. Additionally, 82.4 percent of low-income renter households overpay, meaning that they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, according to the Planning Department.

But not all properties will be affected by rent control, no matter what the Planning Department finds in their study. Under state legislation called the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act of 1995, single-family homes and condos occupied after 1996 and any housing built after 1995 are exempt from rent control. The Costa-Hawkins Act also allows landlords to re-set the rent after a tenant moves out.

That exempts close to half of the housing in Richmond from rent control, said Theresa Karr, regional development director of the California Apartment Association, a statewide association for managers or owners of rental properties.

“Take all of those out and what you have left is a huge housing stock in Richmond that was built during World War II,” Karr said. “These are owned by working people, retired now, people who worked hard to have their own piece of America, who are relying on that rent as a part of their retirement income.”

At last week’s meeting, landlords and other rental property owners backed Karr, like Jeffrey Wright, chief executive of the West Contra Costa County Association of Realtors, who stood to speak out against rent control ordinances, saying that it will make Richmond unattractive to new development.

“The facts do not support rent control,” said Wright. “We are not plagued with the situation whereby rents are exorbitant. We often times can get caught up with the emotionalism of a topic.”

As Wright was leaving the public speaking podium, Councilmember Corky Booze said that he agreed with Wright. At the meeting, both Booze and Councilmember Jim Rogers cited problems the city of Berkeley encountered several decades ago. Rent control was established there in 1980, and afterward developers slowed their building of rental units. The total number of rental units dropped by 14 percent between 1978 and 1990, according to the National Multi-Housing Council, while rental units in neighboring cities without rent control rose.

In 2008, backers of Proposition 98, a statewide ballot initiative, sought to ban local rent control measures, but the measure failed.

“I am not convinced at this point that it is appropriate to go forward with rent control,” Rogers said. “I think that there is evidence that there is a movement away from rental units into condominiums purchasing for single-family homes” in the event of rent control.

But groups like the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) and Richmond Equitable Development Initiative (REDI) are proponents of rent control, saying that it will protect tenants against unfair rent hikes and protect the community from gentrification. “Landlords are still going to make their money” even with a rent control clause, said Melvin Willis, a member of ACCE, which works with low-income residents, immigrants and working families across California. “Let’s just try to make it more fair for the community.”

Proponents argue that landlords can take advantage of low-income residents if there is no control over rent increases. “We don’t want this city gentrified, as the city grows. We don’t want to put low-income people out,” said Councilmember Jovanka Beckles. And with over half the population paying over half their income on rent, Beckles asks, “If rent stabilization is not the answer, what is? It just makes me wonder, what can we do?”

Mayor Gayle McLaughlin also supports rent control. If more Richmond residents can save some money on rent each month, more will be able to afford to buy homes, she said. “Rent stabilization offers these possibilities … and that offers a better economic development situation for the city,” McLaughlin said.“It is a positive to put roots down.”

Aside from being controversial, funding a rent control board is also costly. Several Richmond councilmembers, as well as Rojas, said that board in Richmond is not financially feasible, arguing that paying board members and keeping records could cost the city half a million dollars a year.

“Some of the cities that do have rent control ordinances spend resources in the millions to run that program,” Rojas said. “We don’t have budget surpluses to create new programs. What we want to do is to see what resources we do have.”

Just Cause

Another controversial item in the housing element concerns the establishment of “just cause” eviction protections, which mean that a landlord cannot evict a tenant without legal proof of wrongdoing such as using the property for drug dealing or prostitution. This appeals to some because just cause ordinances protect renters from being evicted if they complain or simply don’t get along with the landlord. However, a landlord also can’t evict a tenant whom they suspect of illegal activities—such as drug dealing—without getting definite proof from the police, which can be time-consuming and ineffective.

Right now, Richmond’s just cause eviction ordinance only applies to tenants in foreclosed homes. However, the Planning Department is now looking into expanding the just-cause ordinance to include all rental properties and will spend the next year doing research.

Proponents of just cause protections believe they give renters more rights and keep landlords honest. Under just cause provisions, landlords can’t evict a tenant with ulterior motives in mind, such as raising the rent on current tenants, and they must follow legal protocols for eviction.

“I am for just cause eviction ordinances because through knocking on doors and talking to community members, I have found that there are good and bad landlords,” said Willis of the ACCE. For example, Willis said, he has heard stories about tenants moving into buildings that aren’t up to code. The landlord pushes the tenants to get repairs made, and when the tenants complain about the extra work, the landlord threatens to kick them out.

But some of those opposed to just cause call it a “drug dealer protection act” since such ordinances can make it harder to kick out a tenant whom the landlord suspects—but cannot prove through police reports—is engaged in criminal activity.

“As much as they would like you to believe, landlords don’t evict good tenants,” said Karr, whose group opposes just cause. “There is not reason to evict a good tenant. Just cause ordinances are developed to where you have to give multiple notices and you have to give them over and over again. It’s just not as cut and dried as it appears.”

Planning Department officials say they will now take the year to gather input from community organizations, legal aid groups, renters, landlord and property owner groups, and study ordinances from other jurisdictions in California to find the most effective regulations for Richmond.

Inclusionary fees

One portion of the housing element that the council discussed without much bickering was an item regarding inclusionary fees. Inclusionary housing ordinances require that developers set aside a certain number of units for low-income residents. If they choose not to, developers must instead pay an “in-lieu fee.”

Richmond and neighboring cities already have inclusionary housing ordinances on the books with in-lieu fees built in. In Richmond, any complex with ten or more units is subject to the inclusionary ordinance. Other cities in the Bay Area charge a fixed in-lieu fee, but Richmond does it based on a percentage of the construction costs, “which I think is more reasonable,” Rojas said.

Money garnered from the in-lieu fees go back into the city’s housing trust fund, which is used to fund more low-income housing projects. “We will get that pool of money together and build our own project,” Rojas said.

Right now, a majority of developers in Richmond pay the in-lieu fee. As a result, that is leaving fewer units available to low-income residents, Rojas said. What he would like to see is to find ways to encourage developers to include the units, creating a more balanced housing environment.

Since the housing element was passed, Rojas will spend the next year talking to developers and neighboring communities to consider changes to the current fee policy. One option would be to require that developers set aside a certain number of units for low-income buyers, regardless of whether they have paid the in-lieu fee. Another would be to raise the fee, which would make it more economically attractive to developers to include low-income units.

At the last meeting, Councilmember Jim Rogers asked Rojas where Richmond stands in terms of in-lieu fees compared to neighboring cities. Rojas replied, “It’s staff’s opinion that we are pretty much in the middle of the pack in terms of in-lieu fees.”

Rogers responded by asking the Planning Department to push Richmond to a higher bracket—to charge higher in-lieu fees compared to the rest of the Bay Area. “I think that it is appropriate for us to have a policy that puts us on the higher end of the pack,” Rogers said.

But if in-lieu fees get too high, it might scare developers away, leading them to build in neighboring cities. With the expected upswing in Richmond’s population in mind, finding the right balance is crucial. “We want to tweak the ordinance to make it more attractive for developers,” Rojas said, “but if we tweak the ordinance, it might have unintended consequences.”

Land Trust

The last element, and the seemingly least contentious at the last council meeting, was a land trust concept. Community land trusts (CLTs) exist all over California, including in Oakland and San Francisco. They are community-based nonprofit corporations that buy land with the intent of providing permanent low-income housing. “Basically it is a way of subsidizing affordable housing for individuals and families,” said Rojas.

Though Rojas thinks it is a great program to help protect the low-income population, it is very expensive. “The idea would be that now that properties are pretty much every where because of the recession, we would be able to afford more properties,” Rojas said. “But the problem with the program is that we don’t have millions and millions of dollars to search for properties.”

Buying the land isn’t the only expense either. The city would need to pay people to operate the program—file paperwork, organize structures and ordinances—and that can get expensive, especially in an already cash-strapped city.

Rojas said the department is still in the initial planning stages, and that while CLTs are a good idea, Richmond would not be able to fund the project without finding a surplus in their budget next year or cutting some funding from somewhere.

The Planning Department will spend a year studying existing Community Land Trusts in California and nationally, gather input from the community, and determine the most feasibility of a possible Richmond Land Trust, as well as the most effective way to structure the corporation.

What’s next?

The rest of the city’s general plan, with elements addressing schools, land use, and health and wellness, easily passed in April, Rojas said. The less contentious parts of the housing element, including clauses addressing Section 8 vouchers and increasing second-dwelling units (backyard in-law apartments), also passed in April. The Planning Division held off until this January on asking the council to approve the four most divisive components of the housing element. “Because there were controversial issues,” Rojas said, “we wanted to fast-track the rest of the plan.”

But until the entire housing element passed, Richmond wasn’t eligible for the grant-One Bay Area Grant. OBAG is a new program funded by federal stimulus money with a goal of funding “streets projects” that enhance the ability to attract development near transit.

The $44 million grant will cover all of Contra Costa County. “But we think that since our general plan and our housing element is so strong,” Rojas said, “we will get a lion’s share of the funding.” Last Tuesday’s meeting fell just two weeks before the deadline to be eligible for the grant money. The council’s agreement that the city will study the four controversial items, rather than of implementing them outright, was enough to ensure the city’s eligibility for the grant.

The Planning Division now has a year to research each item before bringing them back before the council. Rojas said his department wants to work on developing in a sustainable manner, as opposed to just building outward. “We are looking at the growth that is coming to Richmond,” Rojas said. “We want to develop high-density housing, next to employment, that is transit-oriented.”

“In terms of the whole spectrum, we have so much more positive going for us than the negative,” he said.

|

|