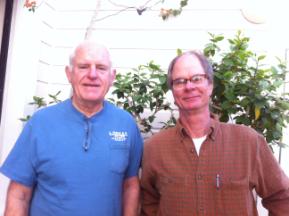

Shirley and I had dinner with Bernhard Horstmann earlier this week in San Francisco. It was only the second time I had seen Bernhard since 1970 in Vietnam. Last time I saw him was in Ascona, Switzerland in 1990, and he now lives in Munich. He was in town for just a day, coming back from seeing a friend in Los Angeles.

Also joining us was Bernhard’s second cousin, Carolin Bellstedt, who is also from Munich and is beginning a six-month internship with Richmond Sanitary next week. She has a degree in Environmental Management and wants to specialize in solid waste management. Carolin is staying with us for a while.

Bernhard has a rather remarkable story that is worth telling.

From left, Shirley Butt, Tom Butt, Bernhard Horstmann, Carolin Bellstedt at Masa’s, December 11, 2012

New York, 1968. Bernhard Horstmann was beginning a career as a 25-year old wine merchant living in New York City when he was drafted. As a German citizen, Bernhard didn’t have to serve; he could have simply returned to Germany.

But he decided to take the plunge. He quit his job, sold his car and moved out of his apartment, taking government provided transportation to Ft. Gordon, GA, to report for basic training.

At Ft. Gordon, he was summoned for an interview with an intelligence officer. Was he born in China? Yes. Had he ever traveled to East Germany? Yes he had. Was he a communist sympathizer? Of course not. Did he have a security clearance or other proof of non-communist sympathies? He did not.

Bernhard was excused and sent back to New York where he had to beg to get his job back and found temporary lodging in a cheap motel.

Just when things were getting back to some semblance of normal, Bernhard got a second draft notice. Apparently, the Army had investigated him and found him to be a thoroughly red-blooded American of German citizenship.

The last thing his boss advised him before he left again for Ft. Gordon was “Don’t ever volunteer for anything.”

Back to Ft. Gordon.

So, only a few days into basic training, it appears that the entire Army cooking staff had been snatched away for duty in Vietnam. “Anybody have cooking experience?” the drill sergeant asked. Forgetting the recent advice about volunteering, Bernhard stepped forward along with six others. Five of them described their meager experience with McDonald’s and other fast food restaurants, but Bernhard, wanting to set himself apart from the crowd, lied that he had been a sous-chef at the Waldorf Astoria.

Next thing he knew, he was in full charge of the mess hall. Bernhard actually had no professional cooking experience, but he found the Army had manuals with detailed recipes for everything. If you could read it, you could cook it.

So Bernhard spent his entire basic training as a chef. Never had KP; never went to the rifle range; never had to march.

He also took the standard proficiency test, scoring high with fluency in three languages and typing speed of 80 words per minute.

But the Army needed more soldiers in Vietnam, so Bernhard had to end his career as an Army chef and head into the unknown.

Now I have to back up here and provide some more context.

Bernhard was born in China to a mother who was the daughter of missionaries and a father who was a German banker. His mother’s father was Chinese. Just before the Communists took over in 1949, Bernhard’s parents divorced, and his mother, then single with four children, had to flee, ending up temporarily in Thailand.

Charlotte Horstmann eventually moved to Hong Kong, where Bernhard received his early schooling. Later, he attended boarding school in Germany while his mother became a highly successful dealer in Chinese antiquities in Hong Kong. Her shop was a “don’t miss” destination for stars, politicians, business magnates and high-ranking government officials from around the world. Click here for a 1982 article in the New York Times.

Eventually, Bernhard moved to New York, where we began this tale in 1968. Eventually, Bernhard moved to New York, where we began this tale in 1968.

Now, back to Vietnam.

In 1969, Bernhard found himself at the replacement depot at Long Binh, sitting around waiting for something to happen. He remembered another piece of advice his boss gave him. “Always look busy doing something, or they will tap you for something you don’t want to do.” This time he took it. So Bernhard grabbed a broom and started cleaning up the depot. As his fellow soldiers lounging around were commandeered for combat duty, Bernhard worked even harder. A man with a mission.

Finally, he was the only one left, and a sergeant asked to see his 201 file. Struck by the 80 words per minute typing skill, the sergeant whisked Bernhard off to Saigon where he was assigned to some obscure unit that seemed to do nothing but create paperwork.

Now it came to pass that as various war correspondents, diplomats and other officials visited Charlotte’s shop in Hong Kong, she urged them to be sure and check on Bernhard when they passed through Saigon. Almost everybody important passed through Saigon in those days.

So it wasn’t long before the sergeant overseeing Bernhard’s paper mill got a phone call from the American Embassy. “Horstmann,” he yelled, “you have phone call.” No E4 got a phone call in those days. It turned out to be the ambassador with an invitation to an Embassy party. “Do you have a suit and tie,” the diplomat asked. Somehow, Bernhard found a suit and began a pattern of attending events and participating in social activities, including membership in the exclusive Circle Sportif Tennis Club, that any other E4 could not have imagined in his wildest dreams.

Resentment, however, began to build up with the lieutenant who commanded Bernhard’s unit, and Bernhard became the target of abuse. “What did you do then,” I asked Bernhard a few days ago when he was retelling this story.

“I called my mother.”

Bernhard was transferred to another unit and treated with more respect.

It was about this time I met Bernhard through another unlikely Army friend, Alan Tolbert. Alan and I had been at Ft. Polk, LA, together in 1968. I was a basic combat training officer, and Alan was a trainee. Neither of us were enjoying our assignments.

It seems that in late 1968, there was a movement to make Ft. Polk a “permanent” installation. It had been built quickly in WWII as a sprawling training facility of mostly one and two-story wood frame buildings not expected to last more than five years. My father had been there briefly in WWII during the “Louisiana Maneuvers.” More than 20 years later, it was still buzzing with activity, having become known as the “last stop before to Vietnam.”

Becoming a “permanent” post would mean lots of money for the local economy and a boon to local politicians. Someone decided that the road to permanency required a “master plan team.” The word went out for architects, engineers and planners.

Alan Tolbert had a master’s degree in City Planning from the University of Tennessee, and, of course, I had a degree in architecture. We both applied and found ourselves part of the brand new Ft. Polk Master Plan Team. We had no idea what we were doing , but we were treated like royalty.

The Fort Polk Master Plan Team hard at work in 1969

After a couple of months, we all got orders to Vietnam, but our civilian overseer was well-connected politically and informed the local congressman that our mission was vital to national defense, not to mention the future economy of central Louisiana and the congressman’s chances for reelection. Some kind of congressional action ensued (we were told it was an investigation), and our orders were postponed for three months.

Eventually, however, the needs of the war surpassed the need for Ft. Polk’s Master plan Team, and we all found ourselves in Southeast Asia.

Alan’s first assignment was quite a comedown. He was assigned to drive the jeep of a lieutenant who didn’t seem to have anything to but drive around the Saigon area. But Alan, ever alert for advancement opportunities, somehow got himself assigned to the mayor of Saigon as a city planner. No one seemed to know what he was supposed to do, but he was assigned an office and a secretary. He was also allowed to trade his uniform for civilian clothes.

Taking advantage of the apparent absence of a superior to report to in the organization chart of his murky assignment, Alan drew up a list of 30 plausible activities in which he could conceivably be engaging and gave them to his secretary. “If anyone calls or comes looking for me,” he told her, “go down the line to the next activity and tell them that is what I am doing today.” When the entire list had been exhausted, the idea was simply to start over. For example, Alan might be “inspecting bridges in Thu Duc” on Monday or “surveying traffic patterns in Binh Thanh” on Tuesday. Remember, this was in the days before cell phones, so no one could check. A modest gratuity to the secretary sealed her loyalty and made her a willing co-conspirator. Now, neither of them had any work they had to do.

But after a short time, no one even knew Alan was there or cared. No one came looking for him.

For the rest of his tour, Alan was a free agent. A “tourist” stuck in Saigon with no schedule and no responsibilities. With little money but an impressive job title, a gift of gab and nothing else to do, Alan gravitated to leisure class activities where he could meet interesting people and sponge off the system. That’s when he met Bernhard at a diplomatic reception.

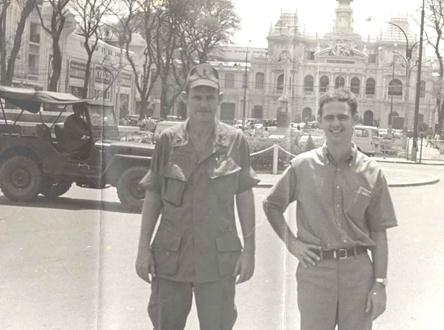

Tom Butt and

Alan Tolbert at Saigon City Hall, 1969

When I later looked up Alan in Saigon, he and Bernhard, along with another friend, had pooled their money to rent a modest apartment where they could hang out and entertain.

The other friend, Eric, (Old Soldiers Never Die.... April 1, 2012) had been trained as an artist and was assigned to a psychological warfare unit where leaflets were designed. The artwork was done in Saigon and then shipped to a printing company in New York. The finished copies were then sent back to Saigon and eventually dropped from aircraft over parts of both South and North Vietnam. This was a pretty routine operation, except that Eric happened to have an old friend working in the New York printing company. A plan for mutually beneficial side business was born. When the artwork was sent to New York by priority US Government transportation, it was carefully packed with a local vegetative material, commonly known as “grass” or “cỏ dai” to avoid damage. E4’s didn’t make much money in those days, and some supplemental income came in handy in an expensive place like Saigon for Eric and his fellow artists.

So, there were the four of us, Bernhard, Alan, Eric and me. An unlikely crew, but we have kept in touch over the years. I was the only one, it seems, who had a real job. I worked out of Long Binh as an Army engineer and spent days building infrastructure all over the greater Saigon area, but I managed to spend many a night in Saigon with my three friends.

Although an American soldier, Bernhard was still a German citizen and carried a German passport. I remember one night we were pub crawling in Saigon, out after the 10:00 PM curfew for military personnel and in civilian clothes. The MPs stopped and questioned us. Bernhard stepped up, presented his German passport, and began to harangue the MPs with a stream of what sounded to me like German obscenities. I stood back, just nodding my head and looking as German as I could. The MPs shook their heads and moved on.

Left, Tom, Eric and Alan in Saigon in 1969. Right, Tom and Eric in 2012

When it came Bernhard’s time to DEROS (date eligible to return from overseas), he gravitated first to Hong Kong where his mother lived. He owed me some money, which precipitated as series of events I describe in Before and After Vietnam 1969-70:

An interesting series of events occurred the day before I left Vietnam for Cambodia. Several weeks before, I had lent $700 to Bernhard Horstmann, a friend with whom I shared the Saigon Apartment. Bernhard had been discharged several weeks earlier and had stopped off to see his mother in Hong Kong and his sister in Tokyo before going back to New York. Bernhard’s mother lived in Hong Kong and was a well-known and highly successful businesswoman in the antique and Chinese reproduction furniture trade. For some reason, which never became entirely clear, Bernhard had left the $700 loan repayment with an employee of his mother with instructions to mail it to me in Vietnam.

The normal way of addressing mail to a U.S. service person is through an APO (Army Post Office), in this case, with a San Francisco zip code. For some reason, the employee addressed the package to me with simply my unit number in “Long Binh, South Vietnam.” To make it even more mysterious, he distributed seven $100 bills in the pages of a paperback book, and included a piece of paper with the page numbers.

Instead of getting into the U.S. controlled military mail system, the parcel went via international mail to the main Saigon Post Office. I received a post card in the mail informing me I had delivery at the Saigon Post Office. I went down to pick it up, and a Vietnamese postal employee said, “Do you wish to accept this?”

I replied, “Sure,” and I signed for it as instructed. Then he said, “ I am a Vietnamese Customs Officer, and you have violated the Vietnam law on currency importation by accepting foreign currency outside legal channels.”

“Great,” I said, “What happens now?”

“Well, you are under arrest, and if you don’t cooperate, we will send you to prison” If you cooperate and confess, we will assess a fine.”

“How much will the fine be,” I asked.

“How much do you have on you,” he replied. I emptied my pockets of about $500 in MPC (Military Payment Certificates), which I had recently withdrawn from the bank in preparation for my trip the next day to Cambodia.

He allowed as how that might be about right, but he also wanted to know my military status and where I was staying. I explained that I had been formally discharged the previous day and that I was staying at an apartment in Saigon. He then decided that they would like to visit the apartment and contacted both the MP’s (U.S. Military Police) and the Con Sat (Vietnamese Military Police). A convoy of jeeps with Customs, Con Sats and MP’s pulled up at the apartment, and we all went inside. As we opened the door, about a dozen decked out Vietnamese women shouted “Surprise!” They were friends of Bui Thi Phuc, all set up for going away party.

The officials told the women to get lost and proceeded to search the apartment. They were intrigued by the phony ID’s I had accumulated and thought that was suspicious enough to warrant a more detailed search. Searching a high shelf in a closet, they exclaimed “Ah ha,” when they discovered a large black plastic bag containing about a bushel of marijuana. It was left over from one or more of my departed roommates; I was not a user of marijuana. With that discovery, they offered the American MP’s an opportunity to take some action, but after confirming that I was no longer a member of the armed forces, the MP’s shrugged and left.

Marijuana was not a big deal in Vietnam, and as far as I know, was not illegal for Vietnamese. My recollection is that it was for sale in public markets. Anyway, we all went back down to the Customshouse. Mr. Thuy told me that I would need to dictate a confession to a Vietnamese typist. Unfortunately, the typist could neither speak English nor type very well. So I typed the “confession” for him because the hour was getting late. While all this was going on, Mr. Thuy sent out for sandwich for me and invited me to take my pick of a beverage from one of several pallets of soft drinks confiscated from who knows where.

Then Mr. Thuy said, “We are through for today. Come back tomorrow, and you can pay your fine.” Mr. Thuy did, however, keep my U.S. passport.

That was a defining moment for me. So far, this looked like just a way to extract $500 from me, but I was concerned that it could be much more serious. I had two choices. I could go directly out to Bien Hoa and catch the next plane to the United States, which my discharge orders allowed (I didn’t need a passport), and leave all the uncertainty behind $500 richer. Or I could play out the routine with Mr. Thuy and follow through with my plans to visit Cambodia as the beginning of an Asian odyssey.

Fortunately, my instincts were right. I went back to the Customs House, paid my fine, took a taxi to Tan Son Nhut and caught the next plane to Cambodia. I was happy but almost broke.

When Bernhard got back to New York in early 1970, he came down with a serious case of hepatitis, the kind you get from tainted water. For months in Saigon, we had been paying a mama san to boil water from the local system, put it in bottles and place it in our apartment refrigerator. After Bernhard left, I found out that she was skipping the critical step of boiling the water, obviously the source of Bernhard’s hepatitis. I have no idea why the rest of us didn’t contract it also.

Serving in Vietnam earned American citizenship for Bernhard, and after leaving Hong Kong, he rekindled his career as a wine merchant in New York for many years, eventually selling his business and moving to Munich where he now lives. I am happy to say he voted for Obama in 2012.

Bernard married and had two sons, one whom is a Harvard-trained lawyer working in London and the other a golf professional in Florida.

Below, a sketch in Ascona form 1990, when Bernhard and I last met.

|