| E-Mail Forum | |

|

|

|

| The Death of Cambodia's Norodom Sihanouk Brings Back Some Old Memories October 16, 2012 |

|

|

Caught in a coup d’état in Cambodia that overthrew Norodom Sihanouk over 40 years ago, I was reminded of those dicey circumstances once again when he died yesterday at age 89. Here is the story. It was March, 1970, when my taste for adventure probably exceeded my common sense. I was in Vietnam, about to complete my one-year tour of Army duty, and Phnom Penh was only an hour away by air from Saigon. I wanted to see Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, one of the architectural wonders of the world. I didn’t know if I would ever get back to southeast Asia, so I took a leap of faith. On the day of my discharge, I chose to forego the coveted “freedom bird” flight back to “the world” and instead boarded an Air Vietnam flight to Phnom Penh, about like flying from San Francisco to Los Angeles. On March 7, I was a uniformed and armed U.S. Army officer in Saigon; on March 8, after an hour’s flight, I was an unarmed civilian in a very strange but beautiful and intriguing country. While Cambodia was once a part of the same French Indochina as Vietnam, it was another world even in 1970. Although substantial North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces were operating from the eastern border regions of Cambodia, the capital was untouched by war and retained that distinctive patina of decaying French colonialism I never saw an American in Cambodia; the foreign visitors I ran into were mostly either French or Japanese. Few, if any, people spoke English, but my remnant high school and college French served me well (Thank you Mrs. Andrews!) Little did I know that Nixon would announce the invasion of Cambodia six weeks later. At that time, Sihanouk was head of state and had been trying to keep Cambodia out of war for a decade. Wikipedia describes the situation as follows: When the Vietnam War raged, Sihanouk promoted policies that he claimed to preserve Cambodia's neutrality and most importantly security. While he in many cases sided with his neighbors, pressures upon his government from all sides in the conflict were immense, and his overriding concern was to prevent Cambodia from being drawn into a wider regional war. In so doing he made difficult choices of alliances in pursuit of the least dangerous course of action, within a political environment where genuine neutrality was likely impossible at the time. In the spring of 1965, he made a pact with the People's Republic of China and North Vietnam to allow the presence of permanent North Vietnamese bases in eastern Cambodia and to allow military supplies from China to reach Vietnam by Cambodian ports. Cambodia and Cambodian individuals were compensated by Chinese purchases of the Cambodian rice crop by China at inflated prices. He also at this time made many speeches calling the triumph of Communism in Southeast Asia inevitable and suggesting Maoist ideas were worthy of emulation. In 1966 and 1967, Sihanouk unleashed a wave of political repression that drove many on the left out of mainstream politics. His policy of friendship with China collapsed due to the extreme attitudes in China at the peak of the Cultural Revolution. The combination of political repression and problems with China made his balancing act impossible to sustain. He had alienated the left, allowed the North Vietnamese to establish bases within Cambodia and staked everything on China's good will. On 11 March 1967, a revolt in Battambang Province led to the Cambodian Civil War. On March 12, 1970, I awoke to the sounds of sporadic gunfire and a hundred thousand people jamming the streets of Phnom Penh. It turned out that Sihanouk was out of the country on a tour of Europe, the Soviet Union and China. It was a coup coup d’état. See Cambodian Coup of 1970. The North Vietnamese Embassy was sacked and burned. U.S. leaders were clearly frustrated with Sihanouk’s collaboration with North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, as was Prime Minister Lon Nol, but CIA involvement in the coup plot remains unproven. Meanwhile, I was running out of money, and therefore time, up at Angkor Wat. The airport at Phnom Penh remained closed as a result of the coup. I had to get to Thailand, but the only way was overland.

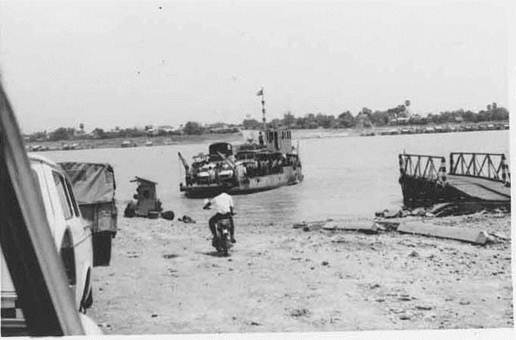

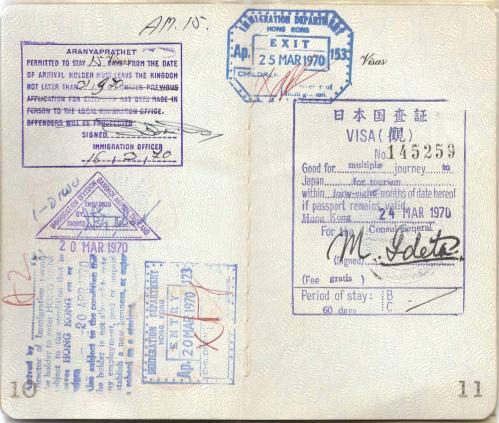

With a small group of westerners, we rented a station wagon and a driver and headed west. At some point, the roads became too bad and too narrow for the car, so we engaged a driver of a motorcycle with a trailer to continue the trip. Finally, as we neared the Thai border, we had to get out and walk across a bridge over a small river where we passed into Thailand at a decrepit border station in Aranyaprathet. Then, it was an obscure jungle outpost. Today, that route is a four lane highway! At the small Thai border village of Aranyaprathet, we boarded a steam train with wooden cars pulled by a wood burning locomotive. It looked like something from a Civil War movie. Within a few hours we had traveled from the heart of the jungle to modern downtown Bangkok.

That was the beginning of an odyssey that took me to Hong Kong, Japan, the Soviet Union via the Trans-Siberian Railroad, Europe, back to Arkansas sometime in May, and eventually San Francisco, where I resumed my life. Three years later, I had completed a Master’s degree at UCLA, married Shirley and moved to Richmond. The rest is history.

|

|

|

|