-

|

-

|

| E-Mail Forum |

| RETURN |

| NY Times - Richmond and Chevron Choose Fork

in the Road November 2, 2009 |

Richmond and Chevron Choose Fork in the Road

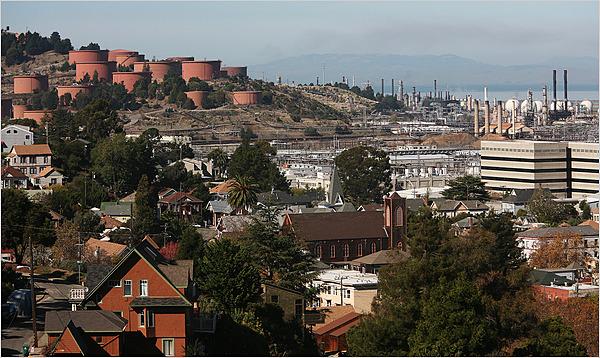

Jim Wilson/The New York Times The fortunes of the Chevron oil refinery fortunes and the city of Richmond have diverged in recent years, creating friction.

Published: October 31, 2009 Richmond and Chevron Choose Fork in the Road By Malia Wollan - New York Times, November 1, 2009 STORY: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/01/us/01sfchevron.html Competing tours offer two very distinct ways to see the industrial city of Richmond in the East Bay. The Bay Area Blog features coverage of public affairs, commerce, culture and lifestyles in the region. We invite your comments at bayarea@nytimes.com.

The New York Times Chevron is Richmond's biggest employer and taxpayer. A “Toxic Tour,” led by an environmental justice group, circles Chevron’s Richmond Refinery and passes through what the group’s local members call the city’s “petrochemical corridor.” On Chevron’s newly offered refinery tours, visitors don hard hats and safety glasses and hear of strict emission standards, exemplary safety records and jobs, jobs, jobs. Chevron is the city’s biggest employer and taxpayer, but in recent years its fortunes and the city’s have diverged. The slowing economy trounced Richmond, while the oil price spike helped Chevron turn record profits. The city and the corporation exist on entirely different scales — Richmond, with a population of 102,120 people, is lost among its larger neighbors, Oakland and San Francisco; Chevron is a global corporation with 62,000 employees operating in more than 100 countries. That prosperity gap helped galvanize segments of the population against the company that has dominated the physical, economic and psychic landscape here for more than 100 years. Gayle McLaughlin, rode the anger into City Hall in 2006. Ms. McLaughlin, the city’s first Green mayor, is now Chevron’s avowed antagonist. As Chevron’s profits climbed, it provided more fodder for her attacks. Until recently, Chevron had been doing well. The second-largest oil company in the United States, it earned $23.9 billion last year, topping off five consecutive years of record profits. Though Friday’s third quarter earnings report showed profits down 51 percent, Ms. McLaughlin still brandishes Chevron’s financial statements like weapons. They contrast starkly with the poverty in this city, which has an unemployment rate of 18 percent and the third-highest crime rate per capita in the state. “It always seems really obscene to me that we have such growing profits experienced by this large oil company while people here are struggling to pay for food and rent for their families,” the mayor said in an interview . A series of lawsuits and a key ballot measure passed since Ms. McLaughlin’s victory show a city torn between the generally liberal, anticorporate politics of the Bay Area and its own history as a loyal company town. Environmental groups have so far been able to block a retrofit of the Chevron refinery while the city has tried to raise the company’s taxes. Chevron, which says the changes to the refinery will reduce pollution, has appealed the ruling. The taxes paid by the Richmond refinery account for 33 percent to 50 percent of the city’s $144 million general budget this year. The refinery employs some 1,300 people, making it unclear what the city would do without Chevron. But between the low profit margins for refineries across the country and the new taxes levied on the refinery, company leaders say they are considering doing without Richmond. While residents might not want anything that drastic, they do seem to want the corporation to do more for the city. Last fall, they passed a ballot initiative, Measure T, whose backers adopted the slogan “A Fair Share for Richmond.” The measure charged businesses an additional tax of a quarter-percent of the value of the raw materials used in manufacturing. For Chevron, that additional tax was $21 million this year. In February the company filed suit in Contra Costa County Superior Court arguing that the measure violated state and federal law. The suit remains unresolved, but Chevron paid the additional $21 million in April. The city kept the money, though it refrained from spending it after the judge in the case warned not to. In February the company also agreed to pay the city $28 million as part of a legal settlement after a city audit concluded that the refinery had underpaid utility taxes. Then, in July, another county judge halted Chevron’s effort to retrofit the refinery, saying the company’s environmental review was unclear on a crucial issue: whether the upgrade was designed to process a heavier grade of crude oil. Lawyers for the nonprofit environmental groups who filed the suit claimed that the use of “dirtier crude” would result in more toxic air pollution and greater danger in the case of an oil spill. While many residents and community leaders are happy with the status quo and grateful for the city’s economic engine, others celebrate the campaign against Chevron. “We will not accept the ongoing chemical assault on our people,” said Dr. Henry Clark, executive director of West County Toxics Coalition, a plaintiff in the lawsuit and an organization that has long insisted that the health of area residents suffers from pollution emitted by the five refineries in the Bay Area. The combination of delays in construction that could improve profits and a fight over taxes that could hurt them are likely to influence the company’s decision whether to stay in the spot where Chevron has been since 1902. The company does not disclose profit figures for individual refineries, but Mike Wirth, a Chevron executive vice president, said Richmond was in the “lowest tier of earnings,” thanks in part to its city and state tax bills. “The government makes more money on the Richmond refinery than Chevron does,” Mr. Wirth said. “We want to be a good partner with the city, but we also have the reality that this facility needs to be competitive and viable,” said Mr. Wirth, adding that the site must compete with other, less regulated and taxed locales like Singapore, China and India. “Refineries that don’t make money don’t stay open,” he said. Brian Youngberg, a senior energy analyst at Edward Jones, said: “Refining is a tough business right now with more refineries coming on line in places like China and an economic slump driving demand down. Profitability in refining is the lowest it has been in years.” Closing the Richmond refinery would probably result in higher gasoline prices on the West Coast, Mr. Youngberg said. Though the threat of closing is a nerve-racking backdrop for the city’s tussles with the oil giant, nothing is imminent. For now, Chevron is working hard to ease the tensions in Richmond and win over the city’s residents. At the end of last year, the company hired a consultant to discover the root of residents’ discontent with the refinery. With those survey results in hand, this year the company will spend $3 million— double what it spent in 2008— to support nonprofits, volunteer efforts and job training programs in the city. In an effort to demystify what goes on behind its gates, the refinery will also offer more public tours. A flood of employee volunteers, wearing brightly colored Chevron T-shirts, has poured into city schools, parks and soup kitchens. To communicate its message directly to residents, the refinery went digital with its own Twitter account, Facebook page and YouTube videos. Ms. McLaughlin said she viewed her struggle against Chevron not just as a local issue, but also as a global one. “We have solidarity with communities in Nigeria and indigenous folks in Ecuador who are also going up against Chevron for destroying their home in the Amazon,” she said referring to the $27 billion Ecuadorean lawsuit against Chevron. For its part, Ms. McLaughlin said, Richmond is now “a city that is growing in its awareness of its own empowerment.” In the midst of the hyperbole, much remains in flux: whether a judge will rule that the city can start spending the $21 million from Chevron in Measure T taxes, whether Chevron wins its appeal and completes construction on the refinery upgrade, whether the company will win over enough city residents by next fall to thwart Ms. McLaughlin’s re-election. On the map of Chevron’s global operations, Richmond clearly remains, if not a sore spot, at least a problematic venue. Mr. Wirth, of Chevron, said he traveled around the world meeting with local officials where the company operates. “Our relationships are stronger in some areas and more a work in progress in others,” he said. “Richmond is a work in progress.” |