Some Marin residents wary of Richmond casino plans

Even though the proposal to build a mega-casino complex is in the

town of Richmond, some Marin residents think its a very bad idea. A

recent editorial in the Marin IJ makes no bones about it.

The $1.5 billion Point Molate casino development would include a

124,000 square foot gambling facility, a 300,000 foot shopping center,

over 1,000 hotel rooms, restaurants and upper end housing on an 85-acre

site.

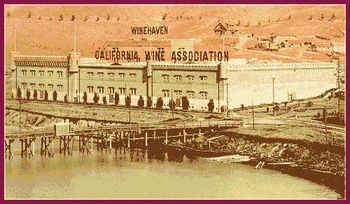

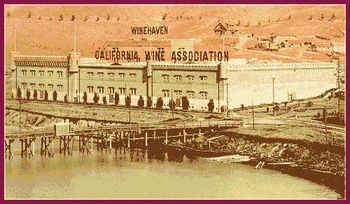

The location--a former turn-of-the-century winery and more recently,

a naval fuel depot--is just north of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge on

the shoreline of the San Pablo Bay near the Chevron refinery, pictured

above. (photo courtesy of PointRichmond.com)

The proposal to build, comes from the

Guidville Band of Pomo Indians who are joined by an East Bay

millionaire, and former Secretary of Defense William Cohen, of all

people.

Even though the proposal to build a mega-casino complex is in the

town of Richmond, some Marin residents think its a very bad idea. A

recent editorial in the Marin IJ makes no bones about it.

The $1.5 billion Point Molate

casino development would include a 124,000 square foot gambling

facility, a 300,000 foot shopping center, over 1,000 hotel rooms,

restaurants and upper end housing on an 85-acre site. The $1.5 billion Point Molate

casino development would include a 124,000 square foot gambling

facility, a 300,000 foot shopping center, over 1,000 hotel rooms,

restaurants and upper end housing on an 85-acre site.

The location--a former turn-of-the-century winery and then a naval

fuel depot--is just north of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge on the

shoreline of the San Pablo Bay near the Chevron refinery.

The proposal to build, comes from the

Guidville Band of Pomo Indians who are joined by an East Bay

millionaire, and former Secretary of Defense William Cohen, of all

people.

Although

it's still in the proposal stage, a

draft environmental impact report was released in July which

included--among other things--a transportation and traffic study. That

particular study is of great interest to Marin, as the casino's

proximity to the Richmond-San Rafael bridge is likely to impact traffic

coming and going from San Rafael. Although

it's still in the proposal stage, a

draft environmental impact report was released in July which

included--among other things--a transportation and traffic study. That

particular study is of great interest to Marin, as the casino's

proximity to the Richmond-San Rafael bridge is likely to impact traffic

coming and going from San Rafael.

Although the EIR seemed to indicate traffic wouldn't be an immediate

issue,

other traffic experts were more circumspect. And a lot of citizen

interest groups have

come out swinging against the casino development proposal, and

lawsuits have been filed. Many people who live in the area don't

think a gambling hall will add to a city already plagued with poverty

and crime.

Several more steps are needed before the developers can even begin to

think about building the complex. The City of Richmond and State of

California will need to approve it, and the developers will need a

federal exemption which would allow them to designate the property as

"restored Indian lands" before anything can be built.

There will need to be public comment, public hearing and public

workshops and a list of those dates and times are on the

Point Molate website here.

(photos courtesy of PointRichmond.com)

Read more:

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/blogs/inmarin/detail?&entry_id=46073#ixzz0PCkIQQPE

Front Page News:

Yeas Outnumber Nays at Point Molate Casino Hearing

By Richard Brenneman

Thursday August 20, 2009

The Planet needs your help.

Give to the

Fund for Local Reporting! One after another, impassioned speakers

from Richmond’s African-American community rose Wednesday night to heap

praises on a Berkeley developer’s shoreline casino resort plans.

The reasons were clear, and cited repeatedly: a plague of violence,

soaring unemployment and a foreclosure rate several said included one in

every four homes in the city.

With the promise of abundant jobs backed by a well-organized and tightly

on-point community campaign, developer James D. Levine and his Napa

partner John Salmon sat smiling during the session, formally a public

hearing to take comments on the environmental review document for the

Point Molate casino resort.

Few of the proponents, who accounted for the vast majority of the

speakers, had anything to say about the document itself, prepared as a

dual-purpose review under the federal National Environmental Policy Act

(NEPA) and the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Their focus was instead to praise the project to the Richmond Design

Review Board, under whose auspices the hearing was conducted.

The campaign, a well-organized effort, which featured several speakers

with name tags identifying themselves as “Point Molate Community

Liaison,” unites unions, business interests and several members of the

African-American clergy to whom the developers have promised a jackpot

of riches, jobs and new business.

Levine and his partners say their $1.5 billion project will restore

dignity and prosperity both to Richmond’s poorest and to the Guidiville

Rancheria Band of Pomos, who would have one of the San Francisco Bay’s

choicest sites awarded them as a reservation if the federal Bureau of

Indian Affairs (BIA) agrees to the proposal.

The hearing, held at Richmond’s civic auditorium in the city hall

complex, ran 80 minutes longer than the scheduled two hours.

The public testimony session was run by Larry Blevins, a BIA

environmental protection specialist from Sacramento, who also heard from

Design Review Board members at the end.

On hand to give an introduction to the massive environmental review

document was Mike Taggart of Analytical Environmental Services (AES), a

Sacramento firm with a long record of preparing successful reviews for

tribal casino projects.

Their 5,284-page draft environmental impact report (EIR) was finally

released July 10, three years after the initially planned release date.

The release triggered a 75-day public comment period during which

individuals and public agency can make comments to be considered in the

final EIR.

Taggart said the report represents the work of 20 AES technical experts

and 14 sub-consultants.

First to speak was Richmond resident Laura Graham. “I just wish there

were a land trust in Contra Costa County that could preserve that land,”

she said, and urged that the project be moved to another site, while

Bruce Beyaert of the Trails for Richmond Action Committee spoke on

behalf of creating safe bicycle access to and through the site and

making sure the Bay Trail was developed along the shoreline.

Leslie May was the first speaker to praise the project, which in its

“preferred alternative” mode would include two hotels with a total of

1,075 rooms, 54 luxury guest cottages and a 240,000-square-foot casino

including 124,000 square feet of gambling area, a 300,000-square-foot

shopping center, two parking garages, a ferry terminal and a public

transit hub.

While Levine had told audiences at public meetings last year that the

project would include a housing component, that element—340 attached

housing units, including three- and four-bedroom townhouses ranging from

1,700 to 2,600 square feet on 32 acres—was demoted to an alternative by

the time the EIR had been printed.

May said the project would provide good construction jobs and provide an

afflicted community “with an opportunity for people to uplift

themselves.”

While it won’t stop Richmond residents from gambling, she said, “you can

bet it will stop them from spending money in places like Plymouth,

California,” the proposed site of another casino.

Jean Womack, a 40-year resident, scoffed at the notion of “trying to put

a tourist industry into a town that doesn’t like strangers and actually

attacks strangers,” instead suggesting sale of the site to Chevron,

which had earlier tried to buy the land from the city.

But Chris Serrano, an unemployed iron worker and another 40-year

resident, said, “This would be a golden opportunity for me. You’ve had

your chance, why can’t our kids have this chance?”

Greg Feere, CEO of Contra Costa Building Trades Council, which

represents labor unions, called the resort “the largest economic

stimulus project for jobs in the entire Bay Area,” offering hard-pressed

workers 17,000 construction jobs. “The only problem I have with this

project is that it isn’t starting today.”

At least three ministers spoke in favor of the project. Rev. Mitch

Robinson, who was also wearing a “liaison” name tag, said that bringing

17,000 jobs to the city would provide “17,000 ways to support my family

without picking up a gun and killing someone.”

Rev. Andre Shumake Sr. of the Richmond Improvement Association, citing

Richmond’s 70 murders in 2008 and responding to a critic who had termed

the promised economic benefits “pipe dreams,” said that “If I have a

choice between a nightmare and a pipe dream, I’ll take the pipe dream.”

“Everything the developer has said he would do, they’re in the process

of doing,” he said. Porfiria Garcia of the St. Vincent de Paul Society,

a Catholic charity, said that while “a casino may create a diversity of

reactions, to the people of the Richmond community, it provides hope and

an answered prayers . . .every day we wait is a wasted day.”

Several residents of the Point San Pablo Yacht Harbor sad they worried

about traffic congestion, and especially access to their shipboard homes

during construction.

Tarnel Abbott, reference librarian at the city’s public library, said

the EIR’s provisions for two counselors to treat gambling addiction

wouldn’t counter the impacts posed by studies showing that problem

gambling rates double within 10 miles of a casino, accompanied by

increases in violent crime, child abuse and neglect, mental health

problems and other issues.

While the casino promised jobs, she said, “the social costs are very

high.”

Andres Soto, Richmond Progressive Alliance activist and one-time city

council candidate, called the EIR deficient for failing to include the

option favored by the General Plan Advisory Committee for the site. He

called the proposed casino project “a pit of unhealthiness.”

But Dr. Henry Clarke of the West County Toxics Coalition, said, “I am

convinced the project supports public health and safety,” adding that

“these developers should be given a reward for the great work they’re

doing.”

Former City Councilmember John Marquez praised the project for which he

had voted during his time on the city’s legislative body. “The major

emphasis in my opinion is on jobs. I hear this every day in the

community,” he said.

Susan Cerny, a Berkeley architectural historian and author, was one of

the few speakers who actually spoke about the EIR itself, addressing

issues of aesthetics and historic preservation.

Cerny said the presence of 160-foot and 120-foot hotel buildings would

have significant impacts on “a very unusual spot with a very unusual

impact” that is already designated a national historic district. She

said she was also concerned about the impacts of reflections from the

high-rises’ windows on commuters crossing the Richmond San Rafael Bridge

and on homeowners and others in Marin County.

But when the public comment session ended, supporters had outnumbered

critics.

When it came time for Design Review Board members to offer their input,

criticism outweighed favorable comments.

“I do have concerns about the economics of the project in terms of

sustainability,” said Raymond Welter.

“From a design standpoint, it’s a massive undertaking in a natural area

and I couldn’t approve it from an aesthetic standpoint,” said Diane

Bloom, who also said she couldn’t imagine that the project’s economic

feasibility is solid.”

Member Andrew Butt said he would like to see more mitigations for

developer plans to demolish a large historic building at the site.

Donald Woodward rattled off a list of criticisms, starting with his

inability to see a real economic need for a casino at the site, given

the presence of many others within 100 miles. He also wanted to see

drawings of how proposed traffic improvements would be built, how the

project could accommodate an existing quarry on the road into the site,

and called the EIR’s coverage of earthquake risks “real.”

Only Otheree Christian, the board’s only African-American member,

expressed unqualified support for the project.

Ellen Whitty said none of the development proposals offered “the highest

and best possible use for the site.”

Chair Michael Wolderman was more reserved in his comments, saying that

while the EIR was “an amazingly complete document,” he still wanted to

see more about how the project would be reviewed by other agencies.

Friday, July 31, 2009

Richmond’s casino plan clears hurdle

Resort’s cost: $1.5 billion

San Francisco Business Times - by

Blanca Torres

The City of Richmond and the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs have

completed the environmental impact report for a proposed $1.5 billion

casino, hotel and resort development on a 415-acre site.

The controversial casino project is expected to generate close to $1

billion per year in revenue, create 12,000 permanent jobs and aims to

raise Richmond’s cachet as a vacation destination. The developers

estimate it would also raise more than $100 million per year in tax

revenue for the city.

The site is a former Naval fuel depot on Point Molate, a small

peninsula just north of the San Rafael-Richmond Bridge. Like many former

base sites, it needs millions of dollars for infrastructure improvements

and rehabilitation of historic buildings.

“We thought that the most viable redevelopment plan would be one that

involved creating a five-star destination resort,” said James Levine,

one of the partners of Upstream Point Molate LLC, which is developing

the site. “There is a $100 million hurdle to do any development ... It

really had to be something that was profitable.”

The plan for the development includes a 240,000-square-foot casino,

two hotels containing more than 1,000 rooms, 300,000 square feet of

retail, 54 luxury cottages, 340 permanent homes and 170,000 square feet

of business, entertainment and conference space. The site will also have

a ferry dock with service to San Francisco as well as open space and

hiking trails.

The Navy transferred 85 percent of the site to Richmond in 2003 with

the remaining 15 percent coming sometime this year. In 2004, the city

selected Upstream, which is made up of four partners, through a request

for proposals and agreed to sell the team the site for $50 million.

Upstream then enlisted the Guidiville Band of Pomo Indians to work on

a plan to turn the site into a casino-anchored resort. The tribe, which

is part of the Guidiville Rancheria Tribe, does not have a reservation

and can request to have land deeded as such by the federal government.

The developers have also partnered with the Rumsey Band of Wintun

Indians, owners of the

Cache

Creek Casino Resort in Yolo County, who have agreed to finance the

construction and manage the casino. Point Molate is a partly secluded

section of the shoreline along the San Rafael Bay. Hills rising 500 feet

provide a barrier from the rest of Richmond. It was settled as a fishing

village, and was used as a shipping port and major wine production

before Prohibition. The former Winehaven winery building is one of 34

historic buildings on the site. Cache

Creek Casino Resort in Yolo County, who have agreed to finance the

construction and manage the casino. Point Molate is a partly secluded

section of the shoreline along the San Rafael Bay. Hills rising 500 feet

provide a barrier from the rest of Richmond. It was settled as a fishing

village, and was used as a shipping port and major wine production

before Prohibition. The former Winehaven winery building is one of 34

historic buildings on the site.

The environmental impact report, several thousand pages in length, is

as complex as the project. To make the casino happen, the developers

will have to go through a complicated process of receiving approvals

from the city, state and federal government. The land will be

transferred from Richmond to the developers to the federal government,

which will put it in trust for the Guidiville Band of Pomo Indians. That

means the tribe has control of the land, but the federal government will

own it.

The report looked at four development alternatives, including the one

proposed by the developers as well as three others with different

options such as a smaller scale development or leaving out the casino

altogether. Other alternatives include turning the entire site into a

park or leaving it untouched.

An economic impact study commissioned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs

in March of 2008 was also included. The document, prepared by consulting

firm

Gaming

Market Advisors, estimates that under the developer’s proposal the

project would cost $1.5 billion to build resulting in a $3.9 billion

benefit for the local economy. The document states that in the casino’s

first full year of operations, projected for 2014, the development would

bring in $959 million in revenue. Gaming

Market Advisors, estimates that under the developer’s proposal the

project would cost $1.5 billion to build resulting in a $3.9 billion

benefit for the local economy. The document states that in the casino’s

first full year of operations, projected for 2014, the development would

bring in $959 million in revenue.

Levine said he is confident the project will reap that kind of

revenue despite the current economic downturn. Unlike other large scale

developments, the Point Molate does not have a major residential

component.

“It’s a real challenge for people to take on these big projects,” he

said. “We’ve come up with something viable.”

Opponents disagree.

Gayle McLaughlin, mayor of Richmond, has written editorials for the

Contra Costa Times stating that gaming is not a stable industry and

would encourage crime. Richmond is already considered one of the most

crime-ridden cities in the East Bay.

A preservationist group, Citizens for East Shore Parks, filed a

lawsuit last January claiming the city’s expedited transfer of the land

to the developers was illegal. Patricia Jones, a spokesperson for the

group, said the suit is ongoing and the group has not had a chance to

fully review the environmental impact report.

The city plans to hold two community review meetings in August and

September.

btorres@bizjournals.com / (415) 288-4960 |